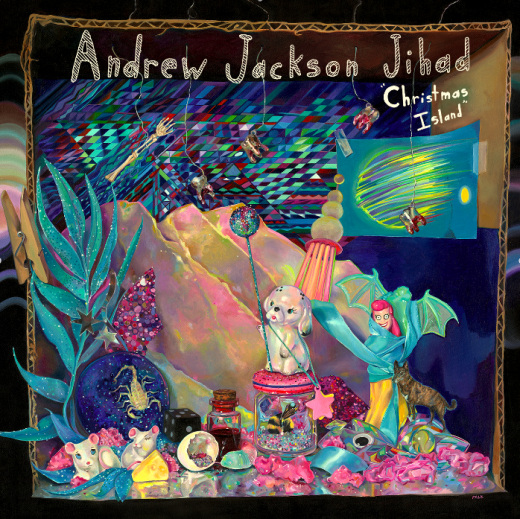

Andrew Jackson Jihad

Christmas Island

(SideOneDummy; 2014)

By Robin Smith | 1 May 2014

Christmas Island is full of gruesome metaphors, and to it, I offer my own: it’s like a band-aid peeling the fuck off. The jokes, which were once Andrew Jackson Jihad’s finest coping mechanism, now go out hunting, and seek to hurt. The songs—with their major key, their bright and triumphantly metal-as-fuck vibe—make you feel like shit. And any time you laugh, which is at least one time a song, you’re left ruminating on how the joke got set up, and what it says about you that you found it funny. It’s a record in which the things that stop other things going sour go sour themselves. It’s a letter of resignation with the words FUCK YOU written over it. It’s a comedian being booed off stage.

It’s also really gross. Sean Bonnette’s songwriting has always been unforgiving, but on Christmas Island it reaches its sad bloody peak. Enough of my metaphors. Here are his: corpses with Nike shoes on them, dogs shitting, people blowing up their neighbours, rats contently drowning. The imagery is almost always attached to the first person—I was this, I am that, Bonnette sings, as if to say these things are as literal as our wasted lives allow them to get. Previous Andrew Jackson Jihad records mixed their comedy and tragedy together so that self-loathing was treated with a healthy dose of toasting to the shitty world outside—being anxious and awkward versus the cocaine people shouldn’t be taking, and oh well, here’s a song about both! But Christmas Island runs them together, saying I’m what’s wrong with the world, so fuck me; “I was a baby-killing Cadillac, now I’m a drug-induced heart attack, somebody’s gotta do it, I know my place.” That line sits at the heart of the record, on one of its only crunchy, amped-up guitar rawk moments (the perfectly calibrated anthem “Kokopelli Face Tattoo”), and it helps you understand why Christmas Island sounds so different: the problems of the world still have punchlines, but now they make you feel numb and resigned.

This new sensation—that the funny in this band’s songwriting isn’t as powerful as tragic, or that it even contributes to the tragic—has a lot to do with the way Christmas Island sounds. It’s largely arranged as an acoustic record, but one that’s straining to evolve into something more hardcore, be it the skramz that develop at the end of “Temple Grandin,” or the way “I Wanna Rock Out in My Dreams,” comprised of licks of Mark Glick’s cello-playing and Preston Bryant’s goofy organ keys, sounds like a metal kid standing on top of the world. That song also sounds kinda like the Magnetic Fields, which gives you a vibe for the unique musical space Andrew Jackson Jihad can occupy: a band labelled dismissively as folk-punk early in their career, they’ve come to care about love songs with couplets as much as they care about powerviolence. They like the Mountain Goats, but they shout out Man is the Bastard. That’s a pretty special line to tread.

Christmas Island is their best sounding record, one that takes actual melodic opportunities to deliver its catastrophic stories. The strings that appear quietly at the end of “Children of God” spar with the heart, and piano gets sprinkled about “Best Friend” like fairy dust on a dirty, unholy surface. The lyrics have face, but how they feel is shaped by the little motifs introduced around them. It sounds like the band are learning new tricks, helped by new members and fresh instrumentals, but really, it’s just that they’re more obvious here. The music can shock without flourishes, too: “Getting Naked, Playing With Guns,” the record’s sparsest song, is also its biggest call-back to their acoustic punx origins, and while it’s set up as a long slog to a killer punchline—in fact, it’s written in such a way that Bonnette sounds like he’s dreamt up a cracking line and written a song around it—it’s not the punchline that sticks out. It’s an inflection in his voice, on the line before, that matters. His voice crackles into what resembles a momentary sob, and then he rallies round on himself and sings Christmas Island’s harshest line: “We’ll blow the little dickhead to smithereens.” When you finally laugh—which you are, of course, obliged to—your stomach lurches a bit.

In a way, Christmas Island feels like a knowing extension of “Big Bird,” the last song from its predecessor, the anthology-like Knife Man (2011). On “Big Bird,” the band internalised like they were putting the finishing touches into a pantomime, turning all their fears and anxieties into a listicle power ballad any crowd could interact with. It was the most epic, curtain-pulling song of their career to that moment, and it pretty well launched them into space—try listening to it without imagining Bonnette and Ben Gallaty being lifted off the stage on strings. With the same sorrowful lyrical content, Christmas Island returns them to earth. Its sinister personal problems get a shrug and its heaviness feels unrelated—there’s a quiescence to how the record sounds when it heats up, when it aggresses, because Bonnette is there to narrate it. “Linda Ronstadt,” a song that gives the band a chance to flex a baroque indie pop sound, describes Bonnette sobbing uncontrollably at a video of Linda Ronstadt, but in the moment, the pathos is just there, existing. Christmas Island is kinda like Bonnette’s experience in this song, I think: it is there to make a mark, and like Ronstadt singing to nobody, it makes that mark in an unexpected moment. It can make you laugh, but its content is deceptively tragic, secretly heart-breaking. It’ll probably be more important after your fifth listen, when it finishes playing and leaves you sitting in silence.

Christmas Island wrings that kind of stillness out. It’s raucous, and it should kick it live, but the way it relates death and misery is clear and unsentimental. Andrew Jackson Jihad toy with ending it on three words that fit such a hateful and chaotic piece of art—“Prepare to die”—but they tack on a more fitting gag, instead: “Bad Lieutenant 2 is the greatest movie ever.” Because, you know, can’t you imagine Werner Herzog singing on this album? All that death and pillaging and excrement; all the apocalypses and sinking ships. I guess not, right, because while it doesn’t have sentiment, there’s empathy in it. There’s the belief, put forward candidly on “Temple Grandin,” that we can “find a friendly way to make it die.” Christmas Island shoots you down and makes loathing the same thing as self-loathing. But it’s also inspiring to listen to. That’s what happens when you kick ass while getting yours kicked.