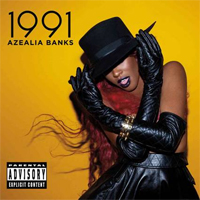

Azealia Banks

1991 EP

(Interscope; 2012)

By Matt Main | 8 June 2012

As I write, #RappersBetterThanNickiMinaj is the number one trend in the UK on Twitter. I derive a mildly amusing irony from this as I simultaneously sift through the lyrics of Azealia Banks’ first official release, the 1991 EP. This because of the innumerable mentions in Banks’ work to other, lesser rappers—often female, although T.I. gets a, um, shout-out in “1991”—many of which are attributed to Nicki Minaj, through a few degrees of separation. Even if you don’t subscribe to the belief that Minaj is being addressed—though I do, mostly—you’d be hard pressed to deny that reminding everyone how great she is via repeated negative reinforcement is a central aspect of 1991, an EP split evenly between shit-talking and talking inconsequential shit. Which, judging from her Twitter feed (specifically her shots at Kreayshawn and, more recently, Lil’ Kim), is maybe how Azealia typically spends her time. For someone so transgressive in her genre, Banks has already found herself in a familiar mire of controversy without even a release to her name.

Perhaps it’s for this simple reason that 1991 even exists: Banks and her changing management can’t seem to decide what exactly she has in the works at any given moment, but recognized it was high time we got a tangible something. 1991 also gives huge web hit “212” a home, along with previous single “Liquorice”; both are welcome reminders of how impressively ready her flow already sounds. Unlike “212,” however, “Liquorice” and new tracks “1991” and “Van Vogue” find Banks mixing her brash young intonation with the sophisticated production of Lone and Machinedrum. Azealia even looks older—compare the baggy-jumper teenager from the “212” video to the Rihanna-esque adult on the cover of 1991. This offers insight into how Azealia views herself developing; “Came in the game with a beat and a bounce,” she acknowledges in reference to “212,” the implication being that she is no longer reliant on those means. The production here emphasizes this growth as well, favoring subtlety and hiccups of techno over bombastic flourishes.

If the appropriation of electronic rhythms makes for a different type of artist, a new Azealia, it is curious that on 1991 she sounds more than ever like Missy Elliott. Right down to the trademarked “ratatata” of “1991,” the pronunciation, bravado, and cadence bears striking similarities, to the extent where it is perhaps paying deliberate homage. This is in sharp contrast to how Banks works, as typically she needs to put someone else’s “bitch” down in order to play herself up. In “Van Vogue,” we get “Vamp me up, turn her down” shortly followed by “Bust your bitch bubble, where’s my crown?”, to the extent where these lines begin to feel like insecurities. Though she might deny it, and insist on being completely insular, Banks is often all the more mesmerizing when she leaves the beef on the back-burner and takes stock of her influences.

Floating around on the Internet right now is a picture of Tyler, the Creator with the caption, “Losing my shock value? Better diss Bruno Mars again.” There’s a parallel to be drawn with Azealia here—a lesson of how the effect of one’s music is diminished when it is choked with the context of controversy. Goodness knows disses and shit-talking are pretty much second nature to a lot of rap artists, but Azealia Banks needs to be careful of how many bridges she burns; again, it’s when she works within the framework of her influences, rather than when she blows them off, that she sounds most exciting. And anyway, 1991 proves she doesn’t need to continue in that direction since she has an important something Tyler doesn’t, something she will hopefully continue to develop from here: an enticing allure without the shock.