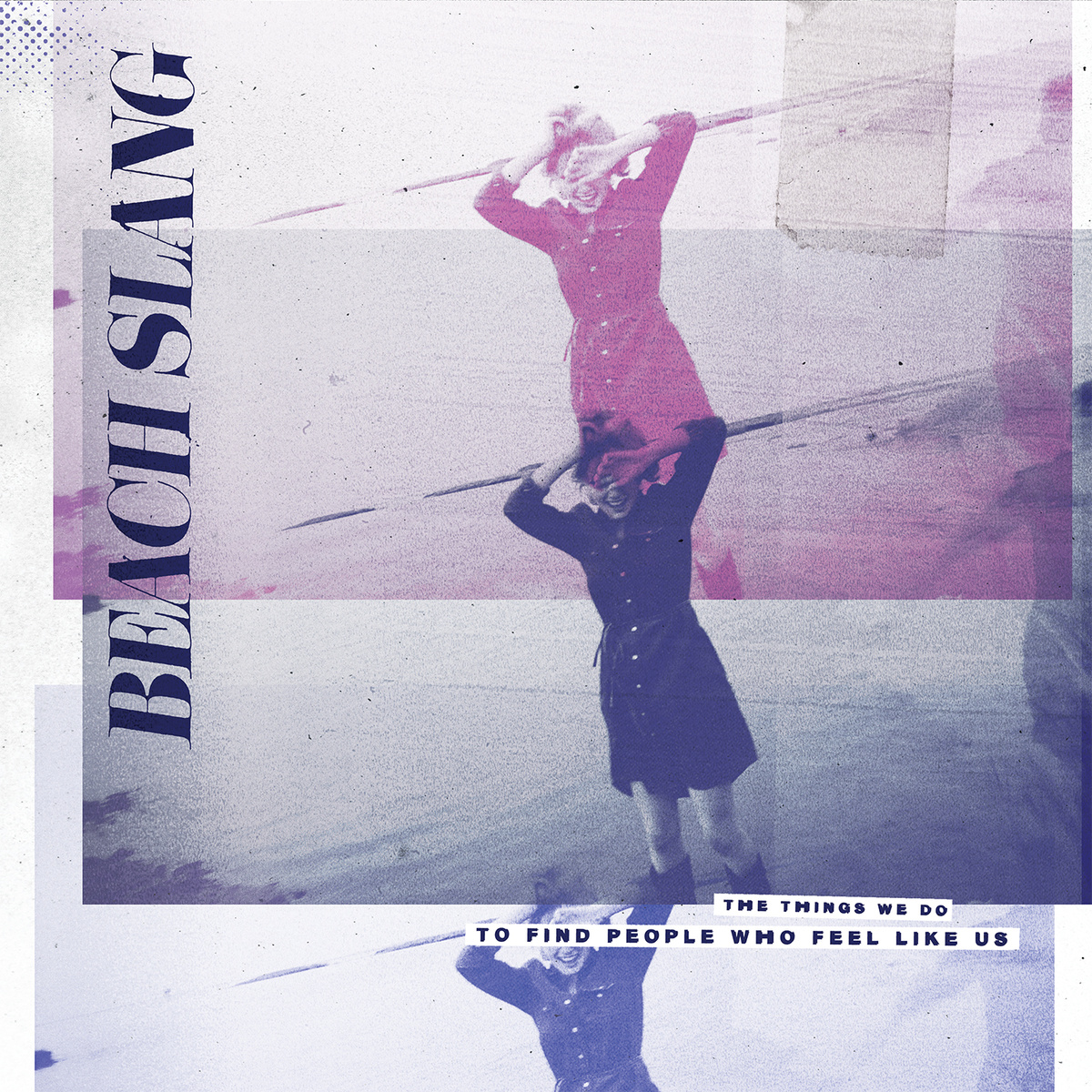

Beach Slang

The Things We Do to Find People Who Feel Like Us

(Polyvinyl; 2015)

By Adam Downer | 9 November 2015

Beach Slang are the last rock ‘n’ roll band. Or rather, they sound like they’ve taken up the mantle of being the Last Rock ‘n’ Roll Band and are embalming the genre’s corpse for its wake. If you took punk rock, Replacements records, and montages about the music industry in the ’70s in movies released in the ’90s, and attempted to distill them to their sentimental essence, you’d get a Beach Slang song. Any Beach Slang song. Doesn’t matter which. They all hit the same notes, literally and figuratively. Nearly every track on the band’s proper debut album, The Things We Do to Find People Who Feel Like Us, relies on wringing a Major IV chord for its anthemic tension while the singer shouts one of a dozen rock ‘n’ roll clichés in an affect that would make Johnny Rzeznik proud. (See: “We are young and alive!” or “The night is alive, it’s loud, and I’m drunk!”) At some point, the amps go to 11. It’s the equivalent of a profile of Kurt Cobain written by a ninth grader, a fawning collage of buzzwords from the Rock ‘n’ Roll Dream not even MTV believes in anymore, a tract for a bloated Boomer notion of a genre already choking on its own hagiography. If rock is dead, Beach Slang are giving its eulogy like someone who barely knew the deceased.

Beach Slang shout platitudes that make adults yearn for the days when platitudes were enough of a rallying cry for their own adolescent angst. Lots of bands do this, and there’s nothing inherently bad about embracing how much your band owes Bruce Springsteen. Japandroids and the Gaslight Anthem effectively do the kind of rock ‘n’ roll pastiche Beach Slang gun for—the difference being those bands actually take a risk once in a while. At one point on The Things We Do, vocalist James Alex asks, “If rock ‘n’ roll is dangerous, how can I feel so safe in it?” The answer: his songs don’t have a single dangerous idea in them. There isn’t one dissonant note on the record, nor a lyric that isn’t an unearned slab of Springsteen-baiting earnestness. To his credit, Alex admits as much when he sings, “The songs I make, I barely rehearse them / They’re hardly mistakes, they’re meant to be honest,” which sounds cool—it’s punk not to care, etc—but it shouldn’t be enough in 2015. Saying “I am telling you the truth” doesn’t mean anything when it’s only followed up by empty sloganeering.

This is Beach Slang’s core problem: they are constantly telling, never showing. They yell “be inspired!” without ever actually inspiring. At one point, Alex sings, “I feel most alive when I’m listening to every record that hits harder than the pain,” unwittingly underlining the cheap conceit running through his band’s music. A lyric like that makes the listener think of important rock records in their own biography, which Beach Slang can then echo with a similar energy and thematic universality. Chances are you like a song that sounds like a Beach Slang song—because Beach Slang songs are what you’d get if you crowd-sourced a rock song. This is why every song on the album is basically the same tempo and uses the same chords: it’s so listeners can remember other, better music. It’s broad, bland, and toothless as shit—practically by design.

The group’s built-in safeguard against criticism is its inherent cheesiness, the idea that “it’s just mindless fun designed to make you feel alive!” That kind of schlock isn’t the issue, here. (We can like schlock, schlock can be fine!) The issue is the band’s implicit insistence that this goopy sentimentality is actually pure, uncut honesty in the service of balls-to-the-wall rocking out—in other words, a grin to hide the truth that the record is a fantasy, propped up by rote rock pastiche. There’s a reason you grow out of your fifteen-year-old self’s ideals, and it isn’t just that you become jaded with age. It’s the knowledge that rock ‘n’ roll alone won’t change the world, that rock ‘n’ roll alone won’t save you. In creating a competent-enough, thoroughly familiar rock record, Beach Slang neglected the one thing that makes the best rock ‘n’ roll songs sing: a purpose.