Black Mold

Snow Blindness is Crystal Antz

(Flemish Eye; 2009)

By Chet Betz | 12 August 2009

Look at us now, readers. The Glow has grown up with you. Remember when Nool would try to write a review like David Sedaris might? Remember, when we dog-piled a My Morning Jacket album like it was so many autumn leaves gathered for us to throw in the air? Remember when we really liked Interpol? Come, let us chuckle sadly together. This is akin to what J.K. Rowling devised in terms of intimately connecting her principal characters to her audience: Harry Potter and Harry Potter’s reader grow together from whimsy, brashness, and color into anxiety, drabness, and hormones. The big difference being that the Glow didn’t really devise anything and we amply succeeded in not making a lot of money off you. And our current equivalent of “hormones” is getting engaged or otherwise preparing the field for settling down. In fact, I’m getting married in about a month and a half; consequently, I can never again write a review like this. I think Dylan has a famous line I could insert here. But I won’t. My writing’s getting too tired for Dylan quotes, too.

Chad VanGaalen has been as integral an artist as any in this maturing relationship of Glow and reader. In one of this site’s earliest reviews our venerable founder Scott Reid lavished Infiniheart (2004), VanGaalen’s debut on the wee label of Flemish Eye, with the kind of ardent praise that only comes from young, impressionable minds. Look at this: “Infiniheart is a stunning achievement that perfectly showcases VanGaalen’s many talents—singer, lyricist, songwriter, producer, and arranger—and though its epic length might be off-putting at first, it won’t take many listens before you’re clamouring for even more.” I mean, it’s been a long minute since I’ve seen Scott clamour for more; we were big-time pimping this unknown artist to you readers—this was a prototype NBH. A couple years later Scott was dissecting Skelliconnection (2006), VanGaalen’s sophomore follow-up on the not-so-wee label Sub Pop, with a bit more measured of a stance—still very much in love but acknowledging the things that could be better and mocking Chad’s rapping. The pimping had given way to honest conversation. By the time Soft Airplane (2008) rolled around Scott—perhaps wishing enthusiasm and verve upon his dear VanGaalen—decided to hand the reviewing reins over to some of CMG’s youngest blood in Alan Baban, but kids today are much older than we were at their age and so Alan professed his undying yet still thoroughly qualified love for Soft Airplane by way of phrases like “rabid peregrinations” and “disburdening involutions” and “post-auricular sheet metal apocalypse.” And each one of us was confused and yet also somehow understood what the review meant and it was because at that point every one of us knew all about Chad VanGaalen and, as Babs intended, we could scribble meaning into the ambiguous blanks of his statements with our own sharpened thoughts. The music world had become our intricate Mad Lib. Which is why we all nod in cold approval when VanGaalen—under the villainous pseudonym of Black Mold—pillages and rapes the bass part of MGMT’s “Electric Feel” for “Barn Swallow vs. SK-1.”

And that brings us, you the readers and we the CMG writers, to now. Now we are so versed, so deconstructive. Now we swiftly consume and on contact parse music into its constituents and those sent to whatever dozen organs of our system need satisfied. Music can no longer hold its own terms against us. We experience its hit in exactly the way we expect to experience it. Quality of craft and content is no longer enough to interest us: I mean, we kind of love The-Dream. Or, more accurately, many of us would rather love-hate The-Dream (dick) than too easily hug, say, Grizzly Bear (teddy). And there isn’t much of a line now between us CMG writers and you CMG readers. Sometimes we are the readers and you are the writers, on your blogs or your message board posts or your tweets that get as many views as our “formal” reviews. We are members of the music literati. We are the assholes, never really open but always ready to opine, to let go a long, low whistle of noxious fumes meant to signify whatever it is we thought about what we just ate.

And the great thing about Black Mold is that it defies us and our assholes. It consists of rare nutrients bound by such insoluble fiber that the whole mass just lays in our stomachs, our “refined” music digestive systems slowly leeching off, bit by bit, the kind of sustenance we so desperately need. The kind of sustenance we can’t fully handle, that affects us in ways we don’t understand. See, this is really the only way I have to describe Black Mold: by describing the shape and mechanics and context of the way in which I can’t describe it. In a very reductive manner I might state that Black Mold sounds like the weirdest extremes of burbling electronic flourish and toy orchestra that have always existed on the fringes and sometimes in the roots of VanGaalen’s music without the tenuous yet unwavering beauty of his voice and the conceptual heft of his words to pull us through to solid ground. But that’s my asshole trying to talk. I could say that “Dr. Snouth” is a Rylan-esque oscillator jam or that the churning chop-dynamic of “Tetra Pack Heads” is something I find “invigorating” or I could go on about immaculate invocation of dope videogame soundtracks that don’t exist. See how my evaluative statements ping and crumple off the true nature of Black Mold like polystyrene bullets. I’m okay with that because now we’re all onto VanGaalen and now we can all experience the joy of him giving us the slip.

It’s brave artist intuition that renders us helpless and I think that’s what we want, deep down. VanGaalen himself is somewhat helpless in the face of his own chance alchemy, his conceiving of combinations heretofore unconceived. It most definitely works—though I’m sure he nearly as much as you or I isn’t exactly sure why. By allowing himself not to know this experimental instrumental music inside out and making sure it does not feel all that familiar to himself and us, he thus knowingly give us something we don’t always know we want: a challenge where there are no shared rules and no ways to win, where we just have to accept the hit that lays us out on our collective music literati ass. Because Black Mold is such an apt name, because this does seem like music as substance (and some foreign and likely illicit substance at that) congealed into one obsidian lump, it all comes off less like something VanGaalen made and more like something he discovered and is packaging then underhandedly passing along to us for our wide-eyed consumption. This is his new shit. He’s taken us back, CMG and CMG reader alike, to the old Flemish Eye days; he trusts us in this cramped place with this dangerous new stuff because we are some of his oldest and most dedicated customers. But when he presents the substance to us we can only look at it—he has to do all the handling. Because, again, we wouldn’t have the first clue how to handle it. VanGaalen is “an artist” and not “a dealer” in this situation due to the apparent fact that he knows just enough.

And the lump that is Black Mold leers impenetrably back at us as VanGaalen somehow breaks us off a _Snow Blindness is Crystal Antz_-sized piece. Emotional cues? Ha. Opening track “Metal Spider Webs” has a string line that could be melancholy but also a bass line that might be playful and maybe ginger chimes and loopy synths and dramatic cymbals and in all the contradictory possibilities none of these things can really be their potential descriptors. Black Mold seems to tell you that if you could just get inside of it it would reveal to you something vital or primordial about yourself, could provide a master key to memories your brain has locked away or that aren’t your own but your DNA’s. This is almost certainly a lie. But because you can never be 100% sure that it is a lie, the fact that it probably is a lie doesn’t matter. You take your toke and the Black Mold still does its job, still thrills the darkest senses. “Wet Ferns,” “Pristine Boobles,” “Swimming to Food,” the title track…these furtively gleaming drippings of decrepit circuitry, skin, and tendon cobbled together will ask you what they are and you’ll only be able to shrug and say “the Truth, I s’pose.”

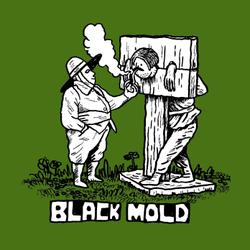

As the substance makes a plaything of your music-listening biology and as it decays within your own decaying body, you feel that decay’s rank passage to enlightenment. Is it addictive filth? There is no pleasure in “Smoking Rat Shit.” We’ll call the cover for the record telling: Black Mold was not meant to please so much as free. But it’s an insular liberation, its limits appalling in their crude constriction. The aesthetic speaks to a new brand of hip enslavement: where nothing can be too beautiful but nothing can be too ugly; where nothing can be too serious but nothing can be too glib; where it all amounts to nothing so nothing says it all. The triumph of Black Mold over this enslavement of the intently middling mean is that it is so incredibly aware of that indenture, reflecting that truth through titles and the infinitely sanguine, infinitely supine way these jams carry themselves. It’s a simultaneous sparkling wink/blank stare VanGaalen throws at us, his thumb pointed over his shoulder at a whole contemporary scene behind him with its head in a stock.

If for no other reason than that VanGaalen is perfectly content to be an intuitive outsider to this “outsider” genre of music that he unplies, his Black Mold tastes fresh and new and, ultimately, life-giving to the likes of us—the readers, the writers, the dutifully imprisoned to our self-inflicted ennui. We won’t be able to grasp it, though. It’s okay. The pipe is being held.