Blind Melon

Soup

(Capitol; 1995)

By Scott Reid | 1 April 2004

Chances are the mere mention of Blind Melon will conjure one of two distinct reactions from people: a) "Oh yeah, that group with that catchy single a few years back, didn’t the singer die or something"; or b) "Fuck Blind Melon." Not everyone would completely write them off with the release of their break-through single "No Rain," but it seems to have marked them in the minds of many as just another hippie rock group celebrating their angst by embracing it like the piles of cash it would make them. They would never have another big single ("Change" was merely a mild success, while "Dear ‘Ol Dad," "Galaxie" and "Toes Across the Floor" would barely register) and any critical acclaim seemed to be dismissed with "yeah, but dude, No Fuckin’ Rain."

For most, it would overshadow their subsequent attempt at breaking through as a serious and talented group — something proven not only by the surrounding tracks on their spectacular debut ("Change," "I Wonder," "Deserted," "Sleepyhouse," "Drive" and "Time" being up there with their absolute best), but even moreso by their sophomore album, Soup. Unfortunately, it would come to be the group’s last album, as Hoon would die just two months after its release, leaving the record’s extreme self-depracation subject to as much conjectural probing by its fans as mourners of Kurt Cobain had done with In Utero.

But upon its release, before the incredible shadow that would be placed over it by Hoon’s untimely death, Soup was — and still is — the statement of a band at their creative peak. Hoon would, as promised by their debut, develop into an incredible lyricist, one obsessed with cryptic nostalgia and self-doubt. Meanwhile, the group’s intricate and abnormally tight arrangements — sharper on "Toes Across The Floor" and "Dumptruck" than they’d ever been — would continue to infuse the songs with a sound that not only stood apart from their debut, but had moved into something that sounded like practically nothing else at the time.

It all begins before the first track even starts; Soup has one of those annoying hidden tracks that comes before track one (you have to rewind past the 0:00 mark to hear it), and for two minutes a sparse acoustic instrumental backing Hoon’s eerie vocals — the vocal track to "New Life" played backward — give us an interesting, albeit superfluous, preface. Though it adds little the record, the significance of the backward inclusion of "New Life" (the album’s only somewhat optimistic track, stuck near the end of desperately insecure song-cycle) to preface the album is striking in the context of what follows.

It cuts out suddenly and the album’s "real" overture, the lax horn-section fueled intro, coyly titled "Hello Goodbye," takes over, and it doesn’t waste much time before getting to the heart of Hoon’s personality faults: "A man like me can easily let the day get out of control." It quickly leads into "Galaxie," one of the record’s catchiest songs centered around more of Hoon’s crippling insecurity; "Can I do the things that I want to do/ That I can’t do because of you/ And I’ll take a left then I’ll second guess into total mess."

"2×4"

and "Vernie" follow, a pair of the record’s most straightforward rock tracks that highlight the group’s ability to transform run-of-the-mill

riff-rock into impeccably structured and remarkably unique beings. For instance, the lead

guitar in the break of "2×4" instantly propels the

song into another stratosphere before letting two channels worth of feedback

and the repeating bass-line fade the song out. "Vernie," a song

about Hoon’s grandmother, works on a more relaxed groove and, like several

other tracks on the record, it completely breaks from its initial

progression about half way through, offering not one but two unforgettable melodies.

Whereas most rock bands include a bridge to merely break the monotony of the verse-chorus-verse structure, Blind Melon were always more interested in using it as a breaking point, a reason to pull the song in a completely different direction. In some cases — like the incredible dissection of childhood and death, "Dumptruck" ("I can’t understand why something good’s got to die before we miss it") or the development into an cacophonic orchestrated march that makes "St. Andrew’s Fall" one of their biggest accomplishments — where the song leads seems to have absolutely no relation to where it had begun other than being a mere afterthought. In the case of "Fall," Hoon uses the closing section, the introspective acoustic lament that follows the full-band midsection, to merely add to the song’s already non-sequitur lyrics; "If I see you walking hand in hand in hand with a three-armed man, I’ll understand/ But you should’ve been in my shoes yesterday."

Were the record to only consist of skillfully constructed psychedelic alt-rock, it’d still be one of the best records of its kind, but Soup is far from homogeneous. Though there are other examples of more familiar rock terrain, like the dumbfoundingly overlooked first single "Toes Across the Floor" — a cut which combines some of the best bass and guitar lines of their career with a series of impeccable hooks and Hoon’s mixture of the caustically personal and abstruse — and latter half inclusions like the effect-laden bong-hit of "Wilt" or "The Duke," which has one of Hoon’s best vocal performances (not to mention some of the most inventive guitar work they ever put to tape), the record made sure to take some brilliant detours along the way.

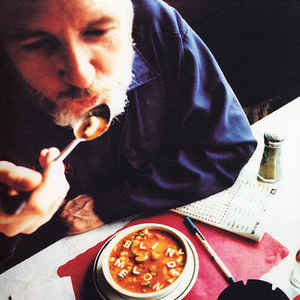

"Skinned" breaks the serious tone of the opening songs with brief blast of banjo and kazoo, while Hoon, laughing his way through the track, takes one of his stranger lyrical approaches, singing from the POV of infamous serial killer Ed Gein: "Don’t you know I’m caught here in the middle, making rib cages into coffee tables. . . and when will I realize that this skin I’m in/ Hey, it isn’t mine." "Mouthful of Cavities" starts in a similarly lighthearted feel (we hear Hoon directing us to hear some cats outside the studio), though the beautiful ballad, a duet with singer/songwriter/actress Jena Kraus, quickly reveals itself as another of Hoon’s acerbic confrontations with death: "Oh please give me a little more/ And I’ll push away these baby blues/ ‘Cause of these days this will die/ So will me and so will you."

"Skinned" is a rare exception to the record’s otherwise completely serious tone, something brought to a head just minutes later with what is very possibly Hoon’s best, and more sincere, composition, "Walk." An incredibly autobiographical and scantly arranged cut, Hoon uses it to cathartically reveal himself in a way only rivaled by their eponymous debut’s "Change." "Finding myself singing the same songs everyday/ Ones that make me feel good when things behind the smiles ain’t ok," Hoon confesses in the song’s opening moments, "and under a sun that’s seen it all before/ My feet are so cold/ And I can’t believe that I have to bang my head against this wall again/ But the blows they have just a little more space in-between them/ Gonna take a breath and try, and try again." Even before Hoon’s death the song struck with the force of a Mack truck, but in light of it, the song is almost unbearably telling of Hoon’s destructive insecurities and inner demons.

"Car Seat (God’s Presents)" is perhaps the record’s strangest number. Its first section, which precedes a phone message of Hoon’s chilling reading of a poem written by his great great Grandmother (which he had tattooed on his arm, as seen on the cover of the posthumous odds-and-ends collection Nico), sounding like he’s reading his own epitaph, takes an atmospherically abstract route that is rarely found elsewhere in their catalogue. With a downright eerie arrangement backing him, Hoon continues in his cryptic focus on mortality and twists on the idyllic childhood: "Feel the thirst, it’s time for pulling over/ Into the truckstop on my daddy’s shoulder/ Out back where they plant all the trees/ Ten feet away my daddy buries me." It stands as not only one of Blind Melon’s strangest compositions, but also by far one of their most viscerally moving.

And yet, on an album so consumed with ruminations of death, insecurity and drug addiction (the aforementioned "2×4" being the most direct line drawn to Hoon’s infamous heroin addiction and unsuccessful attempts at rehab), Hoon did offer one brief moment of optimism near the end of the record with "New Life," which surrounds the birth of his daughter Nico Blue. The song’s pleading tone is, like most of the record, downright devastating in hindsight: "‘Cause now she’s telling me she’ll have my baby/ And a faithful father I am to be/ When I’m looking into the eyes of our own baby/ Will it bring new life into me?" Even confronting the birth of his daughter, his optimism is always followed by a question mark, a mere wish that he can change instead of commitment; the song’s final repeated plea of "Oh please / Bring new life into me" is as desperate as Hoon sounds on the entire record, with the possible exception of "Walk." It’s the sound of a man struggling to find reason to change his path; but, as we would soon find out, it would not be enough.

The record ends with "Lemonade," which would effectively end Blind Melon on a rather odd note. The song, though undeniably catchy and sporting one of the record’s most intriguing structures (the way the song breaks and repeats at the end is fantastic), its lyrics, just moments after "New Life," find Hoon trying to encapsulate nearly every lyrical theme prevalent on the record in a mere three minutes like a brief run-through or list of items that would soon lead to his death. It all comes to an end with a short celebratory reprise of the horn section and the cheering of the band.

It’s hard, even nearly a decade later, to know how to really approach Soup; as much of a cry for help it may have been from Hoon, it was his last attempt to spill everything that would lead to his impending death like blood pouring from a vein, and the songs are no doubt as affecting as they are because of it. Had Hoon been far more stable at the time of its recording, I’m sure it’d be a completely different creature. Which isn’t to say that anyone should be thankful for his state of mind since we were given such an inspired record, but it does mean that what we have with this record is something incredibly rare in any genre, let alone the wasteland that was commerical mid-‘90s rock where very few have approached themselves lyrically like Hoon.

For all of the cryptic messages we can read into as harbingers of his fate, it would be the album’s incredible title track — strangely left off the record — that would hold the most disturbing of lines from Hoon: "Now I’ll close my eyes really, really tight/ And make you all go away/ I’ll make you all go all go away/ And I’ll pull the trigger and make it all go away." Though less direct songs would be eventually chosen for the record, "Soup" sums up the record as well as any single track could. It’s brutually heart-on-sleeve and walks the fine between realization and denial; though he would claim the lyrics were about someone else (Kurt’s name often came up), a single listen of the track erases any doubt of what was really going on in Hoon’s mind. Which is what makes the rest of these songs so disturbingly great; Hoon gave absolutely everything he had to this record — every last thread of fear, disgust and naive hope — and it was a process he couldn’t survive. But he did leave behind one hell of an open diary.