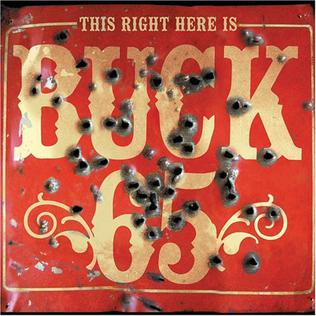

Buck 65

This Right Here is Buck 65

(V2; 2005)

By Aaron Newell | 2 February 2005

Buck 65’s Vertex (my #2 album of the decade thus far) fell into my hands in 1998. Here’s how.

From 1997-2000 I largely ignored my university course work and spent about 4-5 hours a day behind an EMU SP 1200 sampler, the same type used by Buck to produce Vertex, Man Overboard, and large parts of Synesthesia and Square and not all that much of Talkin’ Honky Blues.

The EMU SP 1200 is a relic. It was one of the first sampling-percussion machines widely used by hip hop producers (you could say that, along with turntables, it’s one of the few traditional “hip hop instruments”) and is largely responsible for most of the “golden era” sound from in/around the early 1990s. It’s the thing held up by Doom on the back of the Madvillainy cover. Even on a “modern” record like Stankonia you hear Big Boi asking Dre (sorry, Andre 3000) to “bring the MP and the SP” to the Dungeon Studio. SP’s go for way more on Ebay now than stuff that’s a million times more advanced despite the fact that they have only 16 seconds of memory, a measly 8-bit processor, two (bad) filters, eight channels, and “faithful” reproduction of any sound simply does not happen.

What does happen is a magical, never-has-been-emulated (the MPC 2000 XL 8-bit SP-faker comes close) chunky drum sound that just bumps so nice, so hard, that an adept producer can tap in chopped drum hits and make it sound like a break playing directly from vinyl (see Jel’s work on Themselves and Deep Puddle). Even Sole, who gets accused of twisting everything conventionally “hip hop” into an unidentifiable genre mess, has been quoted as saying “Anyone making any type of hip hop music needs an SP 1200.” Jel has been known to plug his into the board at a live show, load his drum sounds, and play the SP’s pads live like a piano. Slug once said that Jel can put an SP on his lap like a typewriter and program an amazing beat in 5 minutes.

Slug said that to me, actually, as I was taking four hours to work out the sequencing for a song we were recording in 1998. That’s where I got the copy of Vertex, a sixth-generation dub from a beat-up tape deck in Sean Daley’s bedroom with a curtain for a wall. An album done with two turntables, a crap mic, an SP 1200, records that hardly anyone knew had breaks on them, and a cassette four-track over a sleepless 48-hour period. Black Magic. Over the next year and a half I wore out both that tape and my walkman. I still have it in a drawer under my bed, in Slug’s hand “Buck 65 Vertex” is Sharpie-smudged on the maxell ID sticker.

And isn’t that a nice story? While I’m sitting here using this review to swag on the cool people I used to know, you’re like “get to the point.” While my nostalgia certainly shouldn’t be forced upon you, reader, who comes to CMG looking for us to say “buy this, download that, don’t even bother with this, throw diapers at these guys,” this story does end with Sage Francis saying “Buck 65 has his head up his ass," so at least read on for the dirt.

“Back then," in 1998, when I was still idealistic about music, I would sometimes call Rich up and ask him for tips on breaks, or if he might be coming to Newfoundland any time soon, or beg “I need a bassline that does this: “duh duhduduh duuuh” any hints?”. I was backstage pass fanboy, the above mentioned artists all had roommates and shit jobs that they regularly got fired from and found it entertaining that a kid from “where?” had even heard of them, not to mention want to make beats like them.

One phone call to Rich was particularly rewarding. I had been thinking about Buck’s song “The Centaur”; I was writing a paper about it for a Critical Theory course at school. Rich lived in Halifax at the time, and was generally seen by the city’s media (and even a large part of the youth population) as a fucked up little weirdo who probably should be leaving rap music racially segregated. This was back when hip hop was still counterculture and “pure” and your high school hockey team beat up kids whose jeans were too baggy for “wanting to be black.”

The night before I called Rich I had watched Carrie, the ‘70s horror film based on the Stephen King novel of the same name. The beautifully-menacing string sample from Buck’s classic “Centaur” was lifted from that film’s score. Right then, when I heard those strings (as Carrie was setting her classmates on fire), it all sunk in.

Buck’s “Centaur” lyrics are notorious and notoriously misinterpreted. He says “I’m a man, but I’m built like a horse from the waist-down.” He says “I have plenty to say, but nobody listens / Because my cock is so big, and the end of it glistens, so I’m famous for it.” He says the ‘c’-word a zillion times, speaking from the perspective of a porn-bred oversexed man-buck; but his character somehow always retains a striking air of humility, often almost apologizing for the way he “grew” into what he was. “I’m really a nice guy, I’m good at what I do, yes, but all I really want is to listen to Gustav Mahler with my true love, can’t you see that?”

I asked Rich if he wrote the “Centaur” in order to play with his critics. The song can easily be seen as grotesque; on its surface it’s a perverse, quasi-beastial sex rap that at one point was going to be remixed with a vocal appearance by Octagon-era Kool Keith. But “Centaur’s” shocking first impression is its very point: the song wants whoever would jump up and scream “blasphemy, dirty rap song!” to do so, so the rest of us can wink and blow kisses at them.

Recall popular media opinion in 1997/8: hip hop music is sex and violence and violent sex and, simply, wrong (covers of MacLean’s, Time, Newsweek: “Rap is Ruining Our Kids”). “The Centaur” was therefore additional kindling in a small-yet-musically-booming city where Rich had been getting noticed for his break-based radio show, quirky live set, and pronounced hip hop moralizing at a time when people were burning such characters in the town square. Baby-boom-residual pop culture in Canada was still saying things like “Hip hop is not music” or “This is not a respectable artform” (time has shown that “respectable” actually means “money-making” in the popular lexicon) or “This is stolen music by people with no talent” or “DJ’s ruin their parents’ record collections” or “‘MC’s incite violence.”

With “Centaur” Buck 65 was saying, “All you see is my huge, vulgar, obscene (“hip hop”) because that’s all you want to see.” Note: his character listens to classical music, was old-fashioned, a music lover, a poet, but couldn’t shake the stigmatic first impression that it made. To allegorize: anyone who took an interest in Rich’s music either saw him, for better or for worse, as a “rapper."

1997 in Halifax meant Rap = evil. Most people saw him as Buck 65 for worse, hence the shocking pseudo-biography of “Centaur” while, underneath it all, the character as it exists in the song is actually itself a product of popular opinion. Because of society’s prejudices and assumptions, the Centaur’s undercarriage becomes its own effacing logo, and overgrows its personality, its “truth," the person behind it all. And hip hop, if you haven’t noticed, has only ever really been about personality. MC’s don’t show off by scaling octaves or with guitar solos or, until recently, through the extent to which their surgeons can make them MTV-worthy. They impress with attitude, wit and charisma. So when prejudice blinds the critic to the character/personality of the hip hop artist, all that’s seen is the epidermis of an unjust stereotype, and, therefore, not the forward-thinking, counter-attacking, social and/or political undercurrents flowing therein.

I said all of the above to Rich, and hope he meant it when he said “That’s exactly what I meant the song to be, right down to the use of the Carrie sample. And all anyone sees is the sex rap, which is kind of the point anyway, I guess.” Carrie, the character, was herself a person in a small community with a special talent for which she was ostracized (later getting her revenge by burning down her high school and barbecuing the cheerleaders). Rich: “I see myself, and pretty much all kids who are into this music like I am, as pariahs. People see hip hop music as disgusting and artless, but it’s not.”

It was then that I realized that “Centaur” was probably one of the most coherent, semiotically-layered artistic statements I’d ever encountered in music (I’ll stop short at a Braffian “Buck 65 will change your life”). It’s misunderstood, but, even at its most basic level, it illustrates through first-hand-listener-experience how easily context and preconception can lead to misunderstanding. And it does so on purpose, not so much self-defeating as mirroring the cynical listener. Sure it sounds trivial (“oh he took music from a movie about a weirdo and wrote a song about a weirdo because he sees himself as a weirdo, that’s deep), but when you think about the complexity of the presentation, how Rich encapsulated popular opinion/pre(mis)conception, toyed with it like a Bush publicist, evoked shocking-yet-humble imagery to heighten the sense of paradox, and left bread crumbs to the interpretation of the song through the samples he used. . . well, that’s pretty tight-knit. I mean, Oscar Wilde and Jonathan Swift and Bob Dylan and Woody Guthrie did stuff like that, but never Bono, never Sting, never Dr. Phil.

So you now have the proper context for my response to This Right Here is Buck 65: “No, it’s not.”

This Right Here contains two kinds of songs: “new” Buck 65 tracks that employ live music (sometimes instruments played are laundered in a sampler) that are all post-Talkin’ Honky Blues (his most marked artistic shift). The other songs are Honky-style remakes of some of the best-loved moments of Rich’s back catalogue, most notably “Centaur," “Bsc.” (both from Vertex), “Pants on Fire” (single from Man Overboard), “Cries a Girl” (formerly “Stella”), and “Phil” (both from Square).

The newer songs from Honky onwards are largely tangentially-gothic short stories or rapping-redneck treatments of things like fishing (via Woody Guthrie) and trucks. The stories work, the other pieces sort of just reviewed themselves, didn’t they. And while “Talkin’ Fishin’ Blues” and “Big Trucks” are shocking (in the Australian sense of the word, meaning “post traumatic stress disorder”), the remakes are by far the most intriguing to the heretofore loyal fan. The original versions of most of these songs play like sonic equivalents of the fortune-cookie section of Nietzche’s Beyond Good and Evil, one smart, morally-pregnant oneliner after another. This was the stuff that earned Rich his now-waffling legion of miniBucks in the first place. And all of these pieces, in their first incarnations, were very basic, yet genre-stretching hip hop songs: SP 1200-based four-tracked wonders of crate-digging and charisma.

The problem: the updates most often replace the breaks with limp, safe drums (if they retain their drums at all), the songs often lose any inkling of the formerly-beloved Stinkin’ Rich attitude with the simple replacement of certain “iffy” words (one of the things we all loved about Rich’s lyrics was the stubborn resistance to compromise: “I’ve had it up to here with people who don’t think / I’m sick of people asking me why I don’t drink” from “Punk Song” on the Sebutones’ 50/50 Where It Counts – in which song Rich also says: “I’m sick of the rednecks…I’m sick of these God damn compact discs," natch). The new versions aren’t bad, but the Vertex-era fan might quickly become the unwitting recipient of a $20 coaster. As Halifax hip hop mainstay (and Buck 65 idolizer extraordinaire, way worse than me) Jesse Dangerously once disapprovingly said about Rich’s new attitude: “This is personal.”

As far as “Centaur” goes, it should never have been brought to the party if it was on the terms that it be neutered first. The evil strings have been replaced by an Eric-Clapton-circa-your-grandfather’s-bedtime-music acoustic guitar. “My c(l)ock is so clean, and the hour hand is missing” takes a scalpel to the beast’s pride. I realize that you can’t market a song about a sensitive porno horse to fourteen year olds, but the new alternative is a bragging rancher grandfather who grope fourteen year-olds and be more likely to kick a dying horse than put it out of its misery altogether.

One of Rich’s other fine moments of moralizing perfection gets a similar operation. “Pants on Fire” receives a depressing elevator music treatment, Rich even sounding bored and disappointed with himself as he forces out the hook. The line “You spoke my gospel like an apostle / But on the other side of town you got that stuff in your nostril” removes the word “coke” making you think he either: a) signed a deal with Pepsi; or b) consulted with the PTA before declawing one of his best songs. (Note: lines later, Rich also replaces “tight ass” with “taddow," prompting the listener to replace “this is boring” with “click”). Sample clearance may have been an issue, blamelessly explaining away why we lost the furious break and sludge-funky bassline of the original, but if you’re going to reprise the entire song, do you have to sound so sad about it?

Finally, on the upside, recent b-sides “Bandits” and “The Abandoned Cars of Inverness County” (fka “El Dorado”) make welcome appearances. “Inverness County” is arguably one of Rich’s finest storylines, sounding like it could be an extension of his narrative from Signify’s Sleep No More. If you want the good version of “Cries a Girl” (fka “Stella”), you’ll have to get it from Signify as a bonus cut on that disc, or hit up the fantastic Square. One track that does equally well in the no-sample-fees setting is “Phil," but that song is so nice, the guitar so perfect, the lyrics so poetic, that not even Billy Ray Cyrus could screw it up.

Hypothetically.

Talkin’ Honky Blues favourites “Roses and Bluejays” (the quite-touching ode to Rich’s father), “463” (remix version from the single, review linked above), and “Craftsmanship” (the brilliant shoe-shine song, by far the most interesting and ethically-Buck track on Honky) all keep This Right Here’s head above water. “Big Trucks” and “Talkin’ Fishin’ Blues” are, however, embarrassing. On the former the chorus consists of “Take a bubble bath, but not the kind you think (insert mouthmade fart sound here)” so I don’t have to elaborate, and the latter is an annoying, toothless, straw-hat country rant hoe-down that: a) doesn’t match the darkness of the bulk of the release; b) bites; or c) was unscrupulously pried from Woody Guthrie’s sacred body of work just to reinforce V2’s point that our generation’s backroad balladeer has finally arrived. All the way from Mt. Uniacke, Nova Scotia, in a brown truck, with turntables hooked up to a lawn mower. And stuff.

About this time last year, Rich gave an interview explaining that the Talkin’ Honky shift away from sample-based music is due to a desire to “write music” on a guitar or piano with a view to making songs that will “last for as long as possible. . . 10 years, 20 years, 50 years. . . To make a song that could stand the test of time in that way.” In an even more recent interview with Kerrang! Magazine, Rich expanded on this allusion that DJ-based hip hop can’t produce canonical material (for fuck’s sake, whose goddamn canon are we talking about anyway? What the hell is a “classic” or a song that lasts for 50 years, unless you’re talking about cd shelf-life at HMV – your copyright might not even last that long anyway, Rich; do you really think that “Rebel Without a Pause” or “Nuthin But a G-Thang” haven’t been so firmly entrenched in our generation that they will be denied their places in posterity? The beautiful thing about hip hop is that in thirty years it has established itself as a legitimate musical culture worthy of the same respect as “Rock” or “Jazz” and, therefore, I have to conclude that your expressed desire to make music as longstanding as The Beach Boys or The Beatles can only come from your own preconception that there exists a “genre” hierarchy in which guitar pop has more of a right to “classic” status than hip hop, which is selling your own roots short, which is, frankly, not only bullshit, but the antithesis of what your early body of work stands for, and, if you want to go there, sort of counterintuitive to the whole “rootsy” image that you’re riding now. Fuck!).

Excuse that.

OK but in Kerrang! Rich, when pushed, prodded, egged on, and unfairly cornered by an aggressive journalist who, at the end of one of Rich’s longer tours (this one having lasted approximately 4 years, if you’ll check his schedule), essentially called him a “sellout," said this:

“I now hate hip hop, the more I’ve educated myself about music, the more I’ve grown to hate it. I don’t use that word lightly, either.”

And this:

“The change on the new record is me taking steps to try to be regarded as a proper songwriter and not just someone who writes lyrics. Those efforts could lend the idea that I’ve commercialized what I do, but when I think of the greatest records I’ve heard, everything from Nirvana to My Bloody Valentine to Miles Davis and Elvis, there’s a lot you can do within the traditional framework of traditional songwriting.”

Also:

“The people behind hip hop don’t know anything about music theory or have any appreciation for other kinds of music outside hip hop. I challenge anyone to show me a case where there’s actual musicality.”

Which, in particular, is obviously quite a shit thing to say because if it weren’t for “other kinds of music outside hip hop” there would never have been any samples or breaks in the first place. And when Kerrang! asked Rich to explain how a “rapper” could hate hip hop, he responded:

“Every genre of music you can think of has more shit in it than it does gold; what I’m thinking about is the fact that I would be surprised if anyone could show me someone who’s made a hip hop record who could actually read music.”

Kerrang!: “Why should musicians have to be able to read music?”

“Because I’m a snob and that’s what I’m looking for and what I appreciate. I’m as elitist a bastard as you could possibly find.”

Now (I’m almost done, I promise), Buck 65 can DJ better than you can. He knows breaks like DJ Shadow does, probably like Bam does. He can beat-juggle and rap at the same time. He’s worked shit jobs and lived in dives only to spend his grocery money on records. If you do seek “authenticity” in your hip hop then you will have a hard time finding fault in the way Rich developed his craft.

So now, consider, you’re on the road, being asked the same question twelve times/day, and then on the thirteenth it’s by a particularly snotty journalist who’s trying to establish an upper hand, and you give in: you just give him what he wants and are done with it (“I’m as elitist a bastard as you could possibly find (alright?)”).

And then, because you realize that your moment of weakness is now pissing off your entire fanbase of “true heads” you offer this in Canada’s Exclaim! (what is it with exclamation points and music mags?):

“Hello. This is Buck 65 writing in a pre-emptive attempt to address the little controversy brewing over my recent Kerrang! interview. If you haven’t heard about it yet, you might soon. Basically, in the interview I said that hip hop people are ignorant, have no appreciation for other genres of music and that I’d be surprised if anyone could show me an example of a rapper that could read music. I’m apologizing for all that. I lost my cool on tape which is never good. The journalist was provoking me, calling me a sell-out and a whore. I was trying to make a point by playing devil’s advocate, but I went way overboard. No hint of irony or role-playing or intelligence came across in the story. Now I just look like an idiot. I take it back. I don’t really believe any of that. I don’t think being able to read music is a concern. Most of my favourite music was made by non-educated musicians. It doesn’t matter. I still have heavy criticisms of most hip hop, but I really didn’t make them well on this particular day. I put my foot in my mouth and I’m apologizing for that.”

Aside from prompting over forty pages of commentary on the hiphopmusic.com webboard, Rich’s push/pull is interesting simply for the fact that he’s struggling to be everything to everyone. He wants to “uplift” the “average” hip hop fan into a realm of greater musical appreciation, he won’t be stymied by cries of “sellout”, he’ll continue his artistic growth, playahatas be danged (as I’m sure he’d say it these days).

And maybe he has outgrown core hip hop. As my boy Emynd pointed out, Anticon have been slagged for bastardizing hip hop in the past, but really they’re just well-read suburban kids who, before the wave of Urban Music took over the Americas, were influenced by a newer, somewhat taboo artform and turned it into their own brand of wholly-honest artistic expression. Not to colloquialize, but that’s a beautiful thing in itself.

What no one should forget when comparing “hip hop” and other forms of music that retain, to borrow Rich’s term, “musicality”, is that hip hop itself, since its popular, now-mythologized beginnings, never gave a damn for “musicality”. The crux of the art is in stealing your parent’s stereo and records when they’re out of town and throwing a party out of your window, onto the street. You can use the well-tread Rich-rebuttal of “but (FAMOUS GUITAR LEGEND) never learned to read music, what does music theory have to do with anything," sure, and that’s valid too, but hip hop doesn’t even fall into the same paradigm as “live” or “played” music other than for the simple fact that, at the bottom of it, it’s all just music. DXT and Theodore weren’t sitting around deciding whether the word “Fresh” should be written over a bass or treble clef in their exercise books, know what I mean? There were no struggling students teaching neighborhood kids “Apache-blending” to put themselves through trombone school.

And if Buck really wanted to write pop songs like The Beatles and Beach Boys, to crack the code of their longevity, well, didn’t someone do that with algorithms, pattern recognition, and biological response tests like two years ago? And no one cared?

So, really, at the bottom of all this stuff, to me at least, is the immeasurable, massive whole that sweeps over any given artist’s catalogue or body of work that is their “personality," the same thing that lets a long-time Tragically Hip fan know that he should go fishing for “current state of Canada” commentary in every Hip record he owns. The same thing that refines an elusive, ambiguous Bob Dylan lyric into a baby-manifesto. It’s the exact same reason why, when you hear R. Kelly sing something about “ooh baby,” you cringe, knowing that he may just mean it literally. And, on the other side of the coin, it’s the same reason why artist-marketing and image-management has become a mini-industry in itself.

And yeah, someone once said “Worship the music, not the man," but it’s a cop-out to separate the two, and that’s what leads us down the dangerous path of disposable superheroes and artists-as-1010010110’s in the first place. And while I’ll argue to death that you can appreciate a piece of music, literature, or art without knowing a damn thing about where it came from, does it not enrich the “10$” experience to know that M.I.A. is a Sri Lankan refugee who’s so undeniably chock full of attitude that she simply couldn’t help grow up to turn a life-threatening situation into a move to conquer the first quarter of the Hipster Fiscal Year? Of course it does. Am I romanticizing this a little? Of course I am. That’s what it’s here for.

So I’ll repeat: when I hear This Right Here is Buck 65, my gut answer is “No, it’s not.” It’s the sound of something else. And it can quite quickly become the sound of Big Daddy Kane, circa his forgotten (or is it…) Trackmasterz-produced record Looks Like a Job For…, where his lead single was “How U Get a Record Deal.” And I’m not crying sellout, I’m just saying, it’s a shame that no one thinks that anyone wants to buy, worship, love, enjoy for years to come, some of the best hip hop music I’ve heard. Not even one of the best hip hop musicians I’ve heard.

Oh and this is what Sage said on the Non-Prophets forum: “Buck has had his head up his arse for many years now. I’m surprised he’s going public with it. . . Hey Buckaroo. . . I know your manager or current hand-holder will read this and tell you to get your head out of your pretentious asshole.”