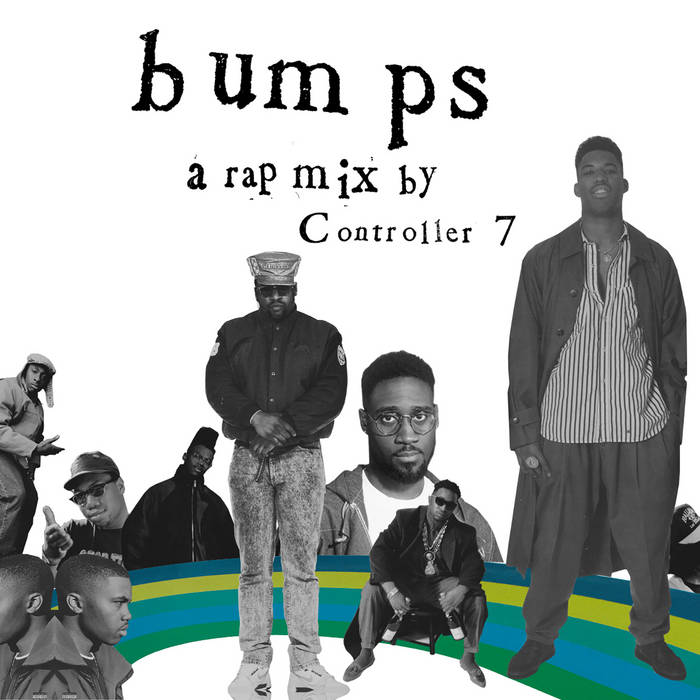

Controller 7

Bumps

(Wenod; 2005)

By Clayton Purdom | 20 July 2005

How to approach the mixtape? This thing is enormous.

I drink a beer, stare at the TV screen, scratch my agitated forearm.

Hip hop. I’ve seen titans of hipness fall at the mere mention of it. We’re all standing in a circle, talking knowledgably about albums we’ve heard, excluding one another in turn (“You mean you haven’t listened to Songs About Fucking?!”) and then promptly shutting up when somebody mentions a Sonic Youth or Pavement album we haven’t 120% internalized. Or a Bob Pollard project. Or whatever. But all in all, everybody’s on roughly the same page; despite various gaps in our musical educations, we’ve all certainly heard a lot of fucking music in our respective days. But then someone mentions hip hop, and a line is drawn: either we’re hip to it, or we’re not. Then there’s the apologetic foot-shuffling from the non-hip-hop-listeners, the, “Oh, I don’t really know that much hip hop, I like that Madvillain album though.” Or it’s some other “approved” act, if not Doom then Tribe. If not Tribe then Jurassic 5. Or the Roots. Or Outkast. Or whoever.

And then on the other end of the spectrum is the guilty fan, obsessed with “realness” (whatever the fuck that is) and making oblique, dubious references to a Cornell West essay that was probably assigned as part of some tier two college requirement (African American Studies 357: From Roots to 2Pac”) at a state university. This anonymous kid gets behind 50 Cent from a purely intellectual standpoint, cerebralizing party jams with feckless urgency, whispering with vague jealousy about “the culture,” and finding lots of other ways to not have fun.

Alright, so maybe I actually took a class like that. (I got a B.) And maybe the casual fan of this whole “indie rock” thing may be able to be into hip hop too, and not be one of those two minimalized archetypes I outlined. But in my limited, Midwestern experiences as a human being, that delineation has been shockingly prominent; the basic terms and names of hip hop can be Greek to the ears of some of the most astute indie rock fans. So the question that I’m getting at is this (I promise Controller 7 will come into play soon): why’s it gotta be like that? It’s not like casual indie rock fans approach electronica (for example) with doe-eyed reverence for the “culture,” though “culture” was as important to electronica as it was for hip hop or for soul or jazz or the blues or punk or any other genre/movement/fiasco.

The most obvious answer to all these questions is that it’s about race: in my neighborhood both the suburban foot-shuffling non-fan and the suburban fervent aficionado feel “excluded” somehow. This is because (okay, I’m going to say it now) hip hop is, at its roots, Black Music. The history books say it was formed as a cultural response to inner-city poverty, and at some point along this line the phrase “liberal guilt” is bound to come up. This means that the suburban indie rock fan from my neighborhood can’t reconcile a sheltered upbringing with a love for hip hop. Every time a boom goes bap, a complex is born.

This is where Controller 7’s earth-shakingly great Bumps mixtape comes in. It’d kill my burb’s youth population — those two scared little archetypes — to know that their shared complex is the same racism they hoped to avoid, only pointed inward. Bumps proves with finality that they’ve got nothing to be scared of. Hip hop was built upon an ethos of cultural inclusion: Afrika Bambataa preached a gospel of almost Utopian acceptance. The culture (no quotation marks this time) grew out of rapturous block parties for Herc’s sake, where the Bronx’s black and white and Latino youth got together to dance to their favorite parts of James Brown songs.

And apparently, an obscure Californian Anticon producer has found a way to distill that infectious, long-lost spirit into a 71-minute mixtape. While there’s nothing inherently revolutionary about a mixtape, Bumps is assembled passionately and meticulously, with one hand flipping through a crate of classics and the other monitoring the party’s pulse. This album is unflagging in its single-minded pursuit of pleasure. Controller 7’s track selection shows some obvious favoritism, with double helpings of De La, Kool G Rap and Nas. This is okay, though, because just look at the caliber of these artists: to review each of these tracks on their own merit would almost necessitate a perfect rating.

Which is why the timid non-fan needs so desperately to pick this album up (and maybe a copy of that Jeff Chang book that all my friends keep telling me to read). Every one of these tracks represents the tip of a discographical iceberg; this disc is loaded with entry points, and evidences what hip hop is/was for the improperly initiated. There’s a circular logic to hip hop, and it goes as follows: old school stuff is the best, and it’s the best because it’s old school. That’s all there is to it, and Bumps presents ineffable proof of this reciprocating, impenetrable truism.

Hear Snoop hungry, spitting words with venomous intensity and making that too-familiar uber-smooth voice of his actually sound menacing. Check Del’s loopy fresh flow on “Burnt,” already in full force a decade before he turned heads with “Clint Eastwood.” MC Lyte is the original (and best) brash female MC, before Lil’ Kim claimed her abandoned throne and tricked the palace out with a bunch of euphemisms for her vagina. Kool G Rap’s seen-it-all thug punchlining and KRS-One’s booming lessons predate both BIG and Pac and all the shameless, tasteless clones that have attempted to fill the gargantuan empty space they left. (Ahem, 50 Cent.) Listen to De La Soul at their goofy best and remember why your snooty friends hate Jurassic 5’s shameless aping. Re-hear Nas on “It Aint’ Hard to Tell” — this remix turns the track from a melancholy nightcap to a sliding, funky boast.

This is a lot for any album to accomplish, but Bumps succeeds brilliantly, giving the uninitiated an opportunity to break in, to put voices to names read years ago in dusty magazines. Mixtapes existed before hip hop, and hip hop mixtapes existed before Bumps, but I’ve listened to plenty, and few are as restlessly encyclopedic as this. So move past Madvillainy, kid; here’s your primer to the good stuff.

But I’m getting in over my head, talking down to the uninitiated as though I were an expert. I’m not — I’ll admit that while I love hip hop, I’ve only scratched the surface in my own exploration of it. So allow me to readjust and address that other extreme, the boring-kid-that-knows-a-lot-more-about-hip-hop-than-me. Yes, he’s fully absorbed the entire oeuvre, from tossed off Peanut Butter Wolf beats to the Amazing Bongo Band to, I dunno, Bone Thugs. But in all this kid’s endless anthropological digging he’s forgotten the urgent sense of community that birthed the music, which is why he now approaches it so analytically, sifting for “realness” and finding desperate mirages. The end result of this quest is either the type of person that finds 50 Cent’s bulletproof vest a suitable substitute for actual mic skill, or the type that’s buried his head in the underground, suffocating quietly in a haze of blunt smoke and slipshod artiness.

This kid needs some Bumps in his life, too. The first ten tracks pay tribute to hip hop’s most comfortable setting, the brag; it’s a reminder that hip hop’s central emotive conceit is respect, and that shit-talking, toasting and bragging are each as important to hip hop as rebellion is to rock’n’roll. The sequencing puts an emphasis on individually lifted verses, but the middle section of the album is dominated by full tracks that exhibit the verbal linguistics that make hip hop’s best MCs so indelible. From MC Serch’s “Back to the Grill” through a pre-Kanye Common Sense (still rapping under his maiden name), the album’s midsection is a testament to the now-cliché hip-hop-as-poetry argument. The album closes just as strongly as it starts, with a series of impeccably mixed classics and a giddy final beat.

If all this doesn’t rescue the bored fan’s love for hip hop from the cold clutches of academia and the pursuit of “realness,” well, that fan’s lost. If all this can’t tear the shyness from the J5 fan and inspire a more thorough listening of the music, well, that kid’s never gonna understand GZA, and therefore he’ll never understand Masta Ace, and therefore he’ll never understand Shan. Hip hop doesn’t have to be relegated and genre-fied; that way of thinking subjugates what is, at the end of the day, just more music for us to listen to and talk about, like Songs About Fucking or Pavement or whatever Bob Pollard project I’m currently sleeping on. Hip hop is just music. Some hip hop is very bad. Some hip hop is very good. Some of it is very “real.” Some of it is very surreal. Some of it is very French. Bumps is a testament to each of these, and it succeeds on all fronts as a vivid reanimation of hip hop’s ghosts, a head-spinning rush of beats and rhymes and life.