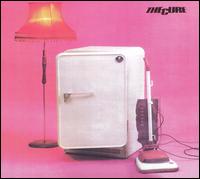

The Cure

Three Imaginary Boys

(Fiction/Rhino; 1979/2004)

By Clayton Purdom | 19 January 2005

Here: Disintegration.

Read it again. Enjoy it, bask in its warm glow. But get it out of your system: because as much as I’d like to pontificate about “Lullabye," the one problem that’s plaguing a modern interpretation of the Cure’s 1978 debut is the context we keep trying to place it in. Robert Smith even voices mixed feelings about it, and everyone else — even fans of the album — view it as an oddity in the band’s cavernous canon, meaning that every analysis of the album as a precursor to what came in the decades that followed is, essentially, a waste of time. Let me put it this way: nobody talks about Duel’s influence on Schindler’s List, even if they do like movies about evil trucks.

When Smith, Tolhurst and Dempsey entered the studio as disaffected, literate not-quite-punks, their aim was to lay down an album of angry pop music with the same raw, unfocused venom of their live shows. The album’s packaging and marketing was hijacked by the label, but upon its release Three Imaginary Boys was acclaimed by the British press as no less than a musical revolution. (The same could be said for Muse, but still.) A year later, the label trimmed up some of the album’s rough ends, tacked on a few more radio-friendly unit-shifting tracks, and re-released it to American audiences as Boys Don’t Cry. The labels were right: the record blew up in the right spots, and the rest is, as they say, history.

So now comes the deluxe Rhino reissue of The Album That Started It All, niftily repackaged and liner noted, with a disc full of demos, rarities, b-sides and live cuts — ostensibly everything a fan could ever want. But my point is this: Elektra didn’t reissue this album so hardcore fans could finally hear where it all began. They re-released Three Imaginary Boys because every post-punk, new-wave, electro-pop, and nacho-funk band of the past four years worth a quarter-column in NME is supposedly “influenced by early Cure."

From last summer’s overblown Curiosa Festival to Gwen Stefani’s ceaseless name-dropping, it’s become oddly fashionable to sheepishly admit to having been a die-hard Cure fan--kinda like KISS was when Weezer first hit, for example. Now artists like Hot Hot Heat, Interpol, Elefant, Saves the Day and the Used are proclaiming themselves devotees of Smith & Co.’s work. Hell, I bet Ashlee Simpson’s worn a Cure t-shirt or two. Call me cynical, but it seems obvious that Elektra’s cashing in on this trend.

Now, I can only spend 425 words talking about the album’s influence and the label’s opportunism because the album itself remains an absolute revelation that, quite simply, speaks for itself. When Smith finally sings, one tense minute into “10.15 Saturday Night," it’s no less than exhilarating; the guitars and drums pump symmetrically alongside one another, now quieter to echo the dripping faucet, now louder to taunt the frustrated protagonist, now tripping over a few beats to emphasize the ached crack in Smith’s voice when he says, “and now I’m cryin’ for yesterday."

There’s not a bad track here (excluding the gag closer), and the range of emotion is astounding by Cure standards, from the cocksure strut of “Accuracy” to the startling, jubilant cover of “Foxy Lady." “So What” is a catchy, convincing kiss-off, even if the lyrics were read off a sugar packet. Better still is “Object," a broken-hearted fist-pumper that would be misogynistic (chorus: “You’re just an object in my eyes”) were it not for Smith’s delivery, which sounds like he’s the bruised one—that petty middle finger of a chorus is his attempt to convince himself he doesn’t care that she’s gone. The title cut is the sort of go-nowhere slow-burner that gets the group lambasted these days, but in this setting, it’s a heart-stopper—a swirling minor-key lament, like the world’s dropped out from underneath, with a mid-song guitar solo that sounds like a slow motion video of a wildfire.

The rarities disc contains some fantastic cuts—check the sneering proto-punk of “I Want To Be Old” or the atmospheric stomp of “Winter”—but Rhino has also unearthed a lot of garbage. The demos are either unlistenable due to shoddy recording or unnecessary because they’re near-identical to the album tracks. It’s baffling why Rhino would exclude “Killing An Arab” from this collection, especially when the band’s other early American singles, released on Boys Don’t Cry, are present. Too much has been said already about <I>that</I> album’s epochal title track, so listen to it again on this collection and remind yourself why; it’s one of the most vital recordings in pop music, stunning in its simplicity and absolutely crushing in its sentiment.

It’s also one of the primary reasons we can thank the musical gods for this reissue. Because when most critics lazily refer to a group as “inspired by early Cure," they’re citing the angular riffs of “Jumping Someone Else’s Train” to a certain extent, but what they’re really talking about is “Boys Don’t Cry." This collection of songs represents one of early alternative’s most influential bands working at its absolute peak. While every gloomy band with half a pop sense claims them as a predecessor, the truth is that the Cure’s influence is much greater than just that. And it’s thrilling to re-hear them — most of all Smith, whose signature voice is already present at 19 — before they were bogged down by celebrity and ambition and were free to make reckless, giddy pop music sound very, very sad.

Read it again. Enjoy it, bask in its warm glow. But get it out of your system: because as much as I’d like to pontificate about “Lullabye," the one problem that’s plaguing a modern interpretation of the Cure’s 1978 debut is the context we keep trying to place it in. Robert Smith even voices mixed feelings about it, and everyone else — even fans of the album — view it as an oddity in the band’s cavernous canon, meaning that every analysis of the album as a precursor to what came in the decades that followed is, essentially, a waste of time. Let me put it this way: nobody talks about Duel’s influence on Schindler’s List, even if they do like movies about evil trucks.

When Smith, Tolhurst and Dempsey entered the studio as disaffected, literate not-quite-punks, their aim was to lay down an album of angry pop music with the same raw, unfocused venom of their live shows. The album’s packaging and marketing was hijacked by the label, but upon its release Three Imaginary Boys was acclaimed by the British press as no less than a musical revolution. (The same could be said for Muse, but still.) A year later, the label trimmed up some of the album’s rough ends, tacked on a few more radio-friendly unit-shifting tracks, and re-released it to American audiences as Boys Don’t Cry. The labels were right: the record blew up in the right spots, and the rest is, as they say, history.

So now comes the deluxe Rhino reissue of The Album That Started It All, niftily repackaged and liner noted, with a disc full of demos, rarities, b-sides and live cuts — ostensibly everything a fan could ever want. But my point is this: Elektra didn’t reissue this album so hardcore fans could finally hear where it all began. They re-released Three Imaginary Boys because every post-punk, new-wave, electro-pop, and nacho-funk band of the past four years worth a quarter-column in NME is supposedly “influenced by early Cure."

From last summer’s overblown Curiosa Festival to Gwen Stefani’s ceaseless name-dropping, it’s become oddly fashionable to sheepishly admit to having been a die-hard Cure fan--kinda like KISS was when Weezer first hit, for example. Now artists like Hot Hot Heat, Interpol, Elefant, Saves the Day and the Used are proclaiming themselves devotees of Smith & Co.’s work. Hell, I bet Ashlee Simpson’s worn a Cure t-shirt or two. Call me cynical, but it seems obvious that Elektra’s cashing in on this trend.

Now, I can only spend 425 words talking about the album’s influence and the label’s opportunism because the album itself remains an absolute revelation that, quite simply, speaks for itself. When Smith finally sings, one tense minute into “10.15 Saturday Night," it’s no less than exhilarating; the guitars and drums pump symmetrically alongside one another, now quieter to echo the dripping faucet, now louder to taunt the frustrated protagonist, now tripping over a few beats to emphasize the ached crack in Smith’s voice when he says, “and now I’m cryin’ for yesterday."

There’s not a bad track here (excluding the gag closer), and the range of emotion is astounding by Cure standards, from the cocksure strut of “Accuracy” to the startling, jubilant cover of “Foxy Lady." “So What” is a catchy, convincing kiss-off, even if the lyrics were read off a sugar packet. Better still is “Object," a broken-hearted fist-pumper that would be misogynistic (chorus: “You’re just an object in my eyes”) were it not for Smith’s delivery, which sounds like he’s the bruised one—that petty middle finger of a chorus is his attempt to convince himself he doesn’t care that she’s gone. The title cut is the sort of go-nowhere slow-burner that gets the group lambasted these days, but in this setting, it’s a heart-stopper—a swirling minor-key lament, like the world’s dropped out from underneath, with a mid-song guitar solo that sounds like a slow motion video of a wildfire.

The rarities disc contains some fantastic cuts—check the sneering proto-punk of “I Want To Be Old” or the atmospheric stomp of “Winter”—but Rhino has also unearthed a lot of garbage. The demos are either unlistenable due to shoddy recording or unnecessary because they’re near-identical to the album tracks. It’s baffling why Rhino would exclude “Killing An Arab” from this collection, especially when the band’s other early American singles, released on Boys Don’t Cry, are present. Too much has been said already about <I>that</I> album’s epochal title track, so listen to it again on this collection and remind yourself why; it’s one of the most vital recordings in pop music, stunning in its simplicity and absolutely crushing in its sentiment.

It’s also one of the primary reasons we can thank the musical gods for this reissue. Because when most critics lazily refer to a group as “inspired by early Cure," they’re citing the angular riffs of “Jumping Someone Else’s Train” to a certain extent, but what they’re really talking about is “Boys Don’t Cry." This collection of songs represents one of early alternative’s most influential bands working at its absolute peak. While every gloomy band with half a pop sense claims them as a predecessor, the truth is that the Cure’s influence is much greater than just that. And it’s thrilling to re-hear them — most of all Smith, whose signature voice is already present at 19 — before they were bogged down by celebrity and ambition and were free to make reckless, giddy pop music sound very, very sad.