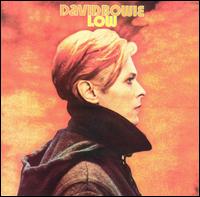

David Bowie

Low

(Virgin; 1977)

By Amir Nezar | 1 September 2005

I would like to see your reviews of David Bowie’s ‘Low’ and Sonic Youth’s ‘Daydream Nation’, seeing as PF rated them the best albums of the 70s and 80s respectively.

–Ed Gordon

An illustrative anecdote about the universal greatness of David Bowie’s Low:

I was once in my family’s house, and after a good livening cup of coffee, decided to put in some music into my dad’s decades-old Onkyo receiver/CD player, to play out of his decades-old JBL speakers. My mom was in the kitchen, making an omelet, and I said, “Listen to this. Do you recognize it?”

My mom started shaking her shoulders a bit, saying, “This is so good! Who is this?” When “Breaking Glass” started, she laughed and said, “This is my generation’s music. It’s David Bowie. This is great. It’s better than that stuff that you discover.”

Tempted as I was to defend my generation’s music, there was no way of denying that she was right. Kid A or OK Computer aside, there are hardly any albums from the last 15 years that can even measure up to the mastery of Low.

To begin with, the thematic genius of Low is a thing to behold: an album that starts off with perfect pop rock, the lyrical subject of which is deeply saddening loneliness. As a reflection of the ’70s, it’s a powerful statement that the image of everyone fucking, snorting, and partying obscured the deep loneliness embedded in their discos and dens (in no small part a reflection of Bowie’s own experience). As a fundamental reflection of the human condition, it’s timeless. You can phrase the plight different ways: sadness has always had a curious way of inspiring song as a coping mechanism (slave songs); or that no pop song can retain the perfect innocence its pretty choruses would imply.

Low is, of course, about being low — being depressed, isolated, and yet subsisting. Perhaps it’s best summed up by the words of “Breaking Glass”: “You’re such a wonderful person / But you got problems / Ohhhhooooohhhhooohoooooohhh / Let me touch you.” Or “Always Crashing in the Same Car”: “I was just going round and round and round / The hotel garage / I must have been touching close to 94 / But I’m always crashing in the same car.” Or most succinctly by “Be My Wife”: “Sometimes you get so lonely / Sometimes you go nowhere.”

Pick your expression of low spirits or loneliness—it’s eloquently expressed in every one of the album’s first seven tracks (not unlike Kid A, incidentally). But to deepen the album’s rewards, Bowie also writes picture-perfect pop rock to go with it. His immense hooks are simply inimitable, his orchestration so deft, that no group I’ve heard since has been able to top his mastery. Cerebral and deeply affecting, the grand melodies of “Be My Wife,” and the classic “Sound and Vision” are matched by their catchiness, energy, and depth of organization. Bowie positively rocks the pop paradigm with “Breaking Glass,” with its unforgettable rising soul chorus in the middle of effortless hooks and an unstoppable bass lead—all of which wrap up in under two minutes.

He goes even farther, though, with his experimental pieces, which embody the prophetic daring of truly brilliant artists. The brooding “Warszawa” is the kind of symphonic fusion of the electronic, tribal, and orchestral that changes the paradigm of melancholic expression from the rocking to the emotively primal. It also anticipates the looping of electronic music, ambient drone, and IDM. The alien “Art Decade” weaves a peculiar minimalist hypnotism that seems a dead-on precursor for Boards of Canada’s Music Has a Right to Children. And “Subterraneans” would be vintage IDM of a nearly Keith Fullerton Whitman cast, if Bowie hadn’t somehow tapped into that vein three decades before Whitman started composing his masterpieces.

Ultimately, what Bowie did with Low is what every great artist does: he displayed his mastery of his chosen genre—pop—and then proceeded to break to glorious pieces the paradigm he set for himself (hence the mannerisms of pop dissolving into primal, wordless enchantment). In that way, my mom’s claim that Low was her generation’s music is unfair. Music of this caliber, inventiveness, and daring feels new for every generation—no matter who has the courage to make it. So it’s my generation’s music, too. It ought to be every generation’s music for ages. It still sounds that alive, urgent, and powerful.