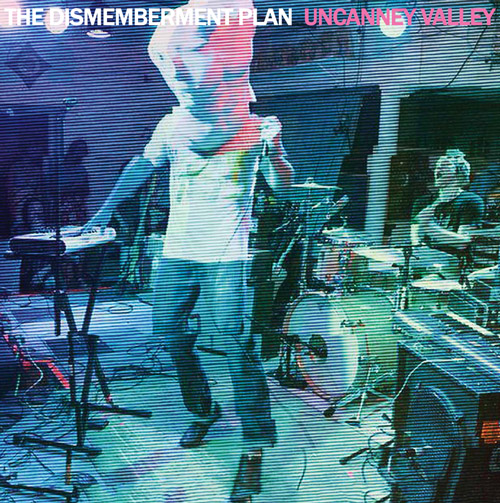

The Dismemberment Plan

Uncanney Valley

(Partisan; 2013)

By Robin Smith | 23 October 2013

Back when they were kids and they rode the train home after work, picturing the apocalypse as any place their friends had moved out of, the Dismemberment Plan weren’t speaking for you. They were delivering you messages. The details were shady and dramatic, the landscapes deceptively barren, the drums chaotic and disorientating, but the important thing was that they had a messenger. Travis Morrison, an unimpeachable indie rock poet regardless of what you and I make of Uncanney Valley, handed listeners his unwound stories like a telegram with the word STOP imprinted at the end of it. His way of finishing the message, though, was with a “Yea”: it confirmed the devastating break-up, or wearily affirmed there was no God (or worse, no one around to party with). Looking back at the band’s two anxious masterpieces now, it’s hard not to hear that word ringing nimbly around the edges. I hear it as a striking double negative in “Gyroscope,” a moment of self-actualization in “A Life of Possibilities,” and the prominent motif of “Ellen & Ben.” As that song breaks out of its bridge, Morrison can’t stop blaring that word at us. He delivers the letter three times over.

The “yea” in “Ellen & Ben” is important. It’s absolute, a signature stamped on the D-Plan’s story at the last moment. I don’t know if Morrison knew Change (2001) was goodbye, and I think he reserves the right to change his mind, but I can’t deny that he elevated the record in its last song. He turned the D-Plan’s story into one that was ending, with characters called by proper nouns and referenced by their possessions. He name-checked Springsteen’s Nebraska (1982) as a side note to unwanted PDA, which is as funny as any full frontal nudity he offered us prior to Emergency & I. Then he ran the song into a rejected-memoir anecdote related to its main story tangentially at best. It was a total curveball to Change, but a whimsical, charming curveball. It feels summative of the band, in its own way. It brought back the side of them that referenced Gladys Knight while their boozy heads spun around and around. Morrison said “yea,” and it was enough.

If “Ellen & Ben” stamped its signature, Uncanney Valley feels like that signature written out again and again (and again, as Morrison stresses on “No One’s Saying Nothing”) until it feels unreal. It has the formula of “Ellen & Ben,” but, you know, twelve years on. Dinky synths chill in the background just because; Morrison’s lyrics sound deliberately asinine, stretched out to make an absurd point rather than a guarded one; even the oscillating trade-off of the band’s emotional state is simplified because it’s suggested they can resolve it. Morrison is looking back on his young and miserable rock ‘n’ roll story with an inevitably charmed disdain for it; like an embarrassing thought he’d care to forget, he faces old anxieties as if he’s clawing his eyes out, or laughing about it with his loved ones. It’s a literal reading of their music, despite its delightfully vacuous bent, rather than figurative. The choruses exist in rubrics, stated once and then twice. Worst of all, if Emergency & I or Change is your collegiate bible (this is not a slight—I am one of you), Morrison’s words stay in one place. Instead of a “yea” that ties up the knots, his stories are laid out on the table.

So he murmurs “You hit the spacebar enough, and cocaine comes out / I really like this computer,” and the problem isn’t the lyric, but its suppression. It’s an “OH FINE, MOM, HOW’S WASHINGTON?” moment without the dramatic stutter or the impassioned yelp; this, because Uncanney Valley resembles most distinctly The Dismemberment Plan is Terrified (1997), their stand-up comedy punx record, but doesn’t spark with its spirit. The reaction to Uncanney Valley is likely to stem from how you feel about Morrison muting his dramas, and how that spills over to his band. Joe Easley’s drumming is tightened, and Jason Caddell’s guitar is asserted less spontaneously, but their understanding for what’s going on is manifested superbly. Uncanney Valley isn’t riotous, but that’s half of the reason it makes me laugh. “Waiting” is the kind of middle-finger love song Morrison would have once made the world’s problem (um, “Following Through”), but in the now it grooves smoothly, the slinky synths brightening the song as if it’s situational comedy: ex-lover walks into a bar, when will she leave? “Invisible,” a skyscraping cut that could have existed on Change, also seems to satisfy itself with a tired wink. Its suspenseful string sample rounds on itself with choruses in which Morrison just accepts his state: “Invisible, yeah, that’s me.”

I’ve accepted that Uncanney Valley is a joke, and presents itself as such—the question is when it lands. I can giggle when Morrison taunts us, squealing “Don’t be such a nerd” over synths that try to place us in a spy thriller. It’s the ridiculousness of the gesture that lands. There’s no direction to it, which explains why the logical conclusion of “Mexico City Christmas,” a song that talks to God, is choruses with “Hi-eeyiii-eyiii!” as their central refrain. Really, though, the saving grace of Uncanney Valley is its resolute tenderness, an emotion the band never coaxed out of their twenty-something gloom. I’ll admit Morrison makes cracks both too stupid and too repetitive for me to want to hear them cracked again—“White Collar White Trash” especially—but like an occasionally out of step friend, most of these songs have a kindness to them that makes me happy for the D-Plan to have aged. “Daddy Was a Real Good Dancer,” with its alt-country guitar swoons, is something I would have never expected to hear from them, because it externalizes. It links two depressions together and shares in them, uniting them over something dumb, like “Daddy’s dancing shoes.” In moments like this, Uncanney Valley uses its silliness like therapy, its jokes like catharsis. Maybe it’s not the weightlessness I feel, but the weight lifted off.

“Let’s Just Go to the Dogs Tonight” is the same. It doesn’t need validation, even though the D-Plan have more access to it, if they want it, than they ever did as a niche indie band fresh out of DC. Its lyrics and melody are straightforward, marching in tandem, and as if pre-empting how surprising that is from one of their records, they invent their own dialogue with their listeners: “When I say what the, you say hell / What the / (Hell!) / What the / (Hell!),” Morrison sings, baiting a crowd he has constructed artificially. He moves onto “Cluster / (Fuck!) / Cluster / (Fuck!),” winking once more, because there isn’t a single clusterfuck to be had on Uncanney Valley. It’s too easy; it’s only surreal if it intends to be. In one of the record’s most offensive tricks (and also its most fitting), the band inject applause into their own song. Their final chorus is cut into by a satisfied crowd, even if the D-Plan have to carve them from their imagination.

Uncanney Valley can clink its own glasses, and I have to wonder if that applause will erupt from the real life crowd I’ll be experiencing the D-Plan with in November. Will it even matter? I felt skeptical of Uncanney Valley in the way I feel skeptical of Robert Pollard’s continued musical presence. It supervenes on something very important, not as much a whole musical narrative is destroyed as the finality of it. Like how “Huffman Prairie Flying Field” will always be the perfect strip landing for Guided by Voices, “Ellen & Ben” is irreplaceable. But it’s also not the last moment of fun to be had, or the last jam either artist thinks they have in them. How do you applaud an artist revoking their crowning moment, but also, how do you blame them for it? I commend Morrison for still being funny, even if he’s not emoting about his shit as significantly, or exploding because of the same pre-adult dramas.

And ultimately, I like that Uncanney Valley is self-administered. It’s why I blame nobody for being unable to empathize with the D-Plan, or care about their music post-Change. I should take a moment here to borrow from Christopher’s reviewing anxieties to say that this record doesn’t really warrant anything. It doesn’t deserve this overlong spiel, nor does it need thought experiments, when all it does is done so easily. Morrison has always been one to present his records’ theses within their first twenty or so seconds, shoving us through the door or having us spin back out of it. Take Emergency & I’s assertion of solipsism: “You dig deep underground now.” Take “There’s no heaven and there’s no hell,” the hopelessly longing, presented-as-fact introduction to Change. Now Morrison’s initiation isn’t about loneliness, or personal philosophy; he has invented a cocaine-computer. It is repulsive, maybe, and certainly stupid, but Morrison is being responsible for himself. That is kind of sweet, even if the message never gets to us.