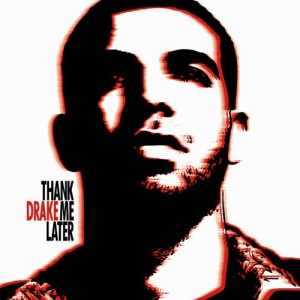

Drake

Thank Me Later

(Young Money Entertainment; 2010)

By Clayton Purdom | 30 June 2010

Hip-hop reactionaries react harder than anyone else—and they always lose, never apologizing, throwing some new shit fit later. Remember how circa-2006 Lil Wayne was fucking contentious? His mixtapes didn’t count because he didn’t have a “real” album! His rhyme schemes weren’t complicated enough! How could he be great when he didn’t have a great single yet?!

But hip-hop—in its constant slow gurgling growth, in its utter unblinking dominance of popular music—remained unphased then, as now, and lo: Wayne is fucking canon today. Because hip-hop swallows everything. Its very nature is assimilation. Debating real hip-hop is an exercise in politics I have zero stomach for, but I have found myself, in loving this thin, divisive new Drake record, positioned to engage in just such politics, and so must remind reactionaries, intemperately stamping their feet, that the come-all cultural credo at hip-hop’s root applied, then as now, musically, too. If we take Illmatic (1994) as a definition, which I am fine with, let’s not forget its etymology as a bastard mutt of electro, punk, soul, funk, dub, and disco, and that it has since swallowed metal, drum’n‘bass, Orlando pop, neo-soul, indie rock, and so on. Hip-hop eats everything because hip-hop refutes irrelevance. It is the Borg of popular art.

And so it’s strange to me that people balk so vehemently at Drake’s sound, which in a jeremiad the venerable Passion of the Weiss assayed as a combination of “Phil Collins, Mase and the Backstreet Boys.” I can’t fuck with this description of it, but I also hold no grudge against the warmly synthesized tones of Phil Collins’ megahits or the point-blank nature of Mase’s slow flow. As for BSB, I assume the reference is to Drake’s heavily manufactured origins, and if we’re going to talk about authenticity, I’m fucking outta here.

Because, hip-hop reactionaries, yes: things have changed a lot since 1994. Drake courts pop audiences unabashedly, tearing a page from Hova’s book and tossing off Tribe and Wu references to keep heads happy but his eyes only on the bottom line. That bottom line, and those pop audiences, are something new today: kids who take their Wiz Khalifa with equal parts kush and Disney music, ones that don’t mind seeing Hayley Williams alongside Playboy Tre on the B.o.B. record. Those reactionary heads that once balked at blog-made mixtape phenoms and trap-hop shit-talkers now turn to them as sacred remnants, with T.I. and Jeezy as new elder statesmen and Hova and Em pushed back further still as “classics,” capable of resting on their laurels, because there is something new happening, and God, do those reactionaries hate it. I’ll call it emo-rap. It’s a horrifying thing to consider. I don’t like how it looks in print.

I shouldn’t. Interesting art affronts, and hip-hop sneakily always affronts through backdoors: a new lowbrow, a new pop form. While Eminem taps into this trend on his totally fucking serious (but, realistically? pretty good) new record, the thrashy, zitty hooks there feel tacked-on to match a trend rather than as a natural growth from the verses. Kanye and Cudi did it boringly, Wayne gratingly, Wiz cluelessly, Roth whitely, Freeway Philly and B.o.B. exuberantly. Drake, on the other hand, comes by emo-rap honestly, like, say, Sunny Day Real Estate or Bon Iver, sounding sad even when trying to sound happy and exuding all this self-centered whininess as though it were an emotional necessity rather than an aesthetic one. He gets laid a lot. He gets sad about it. He lives for the nights he can’t remember / with the people he won’t forget (he actually says this on “Show Me A Good Time”). Then he writes a song about it, probably so he can get laid more. Emo is, if nothing else, a closed system.

None of which (emo-rap, Drake’s honesty) would particularly matter if Thank Me Later weren’t such an outright enjoyable listening experience, dashingly contemporary and rich with sonic pleasure. Like Betz says, he is a motherfucker of an executive producer. This curatorial intellect appeared fully formed on So Far Gone (2009), a combination of midnight soft-rock and Houston thump that played against one another intoxicatingly, particularly when Drake emphasized the thump. On Thank Me Later he has played to the best of its predecessor’s formula by inverting it, eschewing that album’s song-first ethos for an emcee-first approach, and in the process excised all dud tracks, tightened the runtime, and polished each individual song into its own narrative. His in-house producers have stepped their game up immeasurably, draping silky synth lines over plush, easy drums, and the outsourced beats are stunners. “Over” may go down as one of the worst lead-off singles ever, because not only is it completely different from the rest of the record but it requires that context to work at all. Here, its staccato structure throws the sweetly sanguine tones of “Karaoke” and “The Resistance” in stark relief, and its unerring sweep and intensity finds immediate resolution in the ivory-tickling boom-bap bliss-out of “Show Me A Good Time.” That transition alone, and how “Good Time” introduces its musical elements, is worthy of its own essay.

Indeed, Thank Me Later is a structural masterclass, the seven minute slow-fuck centerpiece “Shut It Down” segueing softly into “Unforgettable,” which takes over a minute to form into a rousing Jeezy hook. Guest utilization, like sequencing and beat selection, proves to be another of Drake’s strong suits, whether it was the attention-grabbing indie lifts of his last mixtape or the sequence of gigantic co-signs he receives here, each guest emcee masterfully matched to the beat and the album’s overall ebb and flow. It is unbelievable to me that an album called Thank Me Later ends with a track called “Thank Me Now” and that this works, a six minute stretch of deep-breath “straight” rap that feels like a toast at an underdog’s victory party. Because let’s not mistake that, commercially and critically and sonically, this record is just that: a success where so many, myself included, expected embarrassment. I mean, we all heard the Kid Cudi record, right? No? Exactly.

But we have all heard this record, and will continue to do so throughout the summer, and this will apparently according to the Internet be awful for a large subsect of the population that fucking hates Drake. Thank Me Later has received so much criticism that Village Voice‘s Zach Baron collected and gingerly counterpointed—an act which then warranted its own counterpoint, the fan sucking all the shit back onto its blades. Would, for example, that I could address more of Betz’s points in this counterpoint, but, as I’ve suggested above, I simply do not understand his arguments against this record. Betz’s and my Taste in Things are normally two Venn diagrams snuggling serenely, but here is a wild aberration, cutting against the core of his person and nourishing mine, and I do not get it. It seems like he’s okay with Drake’s emceeing, loves the guest spots and a few tracks on here, and is okay with the rest; he even rated it pretty highly—for Betz—at 64. And yet, he fucking hates it. Read the review: it’s vitriolic, despairing. Aren’t we hearing the same record? Don’t we both pretty much like it (only: me moreso)?

It’s not Drake on the mic. The people that hate Drake held his limited mic skills against him initially but have let those beefs drop. His flow is tight but unfettered, with punchlines that work as easy as a key turns a lock (“She was fine like a ticket on the dash”), and he gilds these verses with auto-tuned melodies. While these qualities rile detractors somewhat he proves himself completely capable of carrying a record vocally—he is an unobtrusive presence, at least sonically, which is more than can be said for many of his peers. He is pleasant. And it is not this unobtrusiveness that they hate, because it is unobtrusiveness that T.I. has made an art. What people hate about Drake has little to do with the actual music he makes and everything to do with the person behind it. It is not a cult of personality supporting Drake—we can all admit there isn’t much personality to make a cult around—but it is a cult of personality against Drake. They abhor this kid whose origin is not so much nebulous as both Jewish and Canadian, a well-fed born-rich child star, his cred unearned but infuriatingly immediate. This is not a charge of racism, xenophobia, or even classism so much as nonhiphophobia, these people terrified and furious that Drake has not earned the narcissism or pessimism he exudes. These people could most accurately be described as “haters.”

Still, charged as I am with reviewing the actual music here and not its cosmological implications, I’d prefer this argument have been finished with my conclusions about the artist’s sonic creation, which Betz’s criticisms don’t much apply to. His reasons are supernatural and debunk themselves in the space it takes to consider them. To wit: if you are hearing this music and like it, then you like this music. Drake is not God; he is an egotistical pop star within the greater genre of hip-hop. Any pop star would ascend to Heaven if we let them, which is why we don’t. The way to the top of the pop charts is paved with false and fallen gods. Those who rise untethered either crash horrifically to earth (Britney Spears, Michael Jackson) or inflate until their artistic heart is forgotten within the bloat (U2, Jay-Z). Drake may do any of that, or none at all. He is guilty of narcissism, cynicism, even a blank sort of stupidity—so, indeed, are my other fifty favorite rappers, to a one—and, as Ryan Dombal smartly points out, he should also be credited with a lot, too. The people that hate Drake allow his music hesitant merit but despise him personally, and will scoop from anywhere to justify this distaste, but they more often than not mistake his music for the people it supposedly appeals to. This is an act of intellectual weakness. Rallying together on the Internet, these haters do what they gonna: hate, blackly fostering a little web of antipathy that exists because the Internet’s lifeblood is argument, necessitating a counterpoint to any point, even if that point was initially nothing more than a very nice, very pretty, and sort of sad pop record by a kid with no interest in keeping his genres straight.

All of which can be distressing for a guy like me, but it’s okay. I can always just go outside.