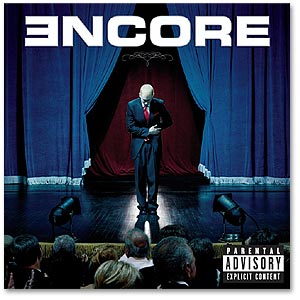

Eminem

Encore

(Aftermath; 2004)

By Matt Stephens | 5 September 2007

During his peak years as a rapper, with the Slim Shady and Marshall Mathers LP’s, Eminem was the best kind of shock artist: he challenged our notions of art and celebrity, cleverly mixed messages of love, envy and contempt for his audience, and offended the sensibilities of people from all walks of life (indeed, anyone who can unite the religious right and the gay community against anything or anyone deserves to be commended). It also helped that as an artist his aesthetic was so singular, drawing subtlety from obscenity and finding obvious glee in making his audience squirm, but leaving the more discriminating listener asking themselves why Eminem’s words made them feel the way they did. Most importantly, he was perhaps the most technically proficient rapper of all time, as good at toying with mind-bendingly complex rhythms and meters as any rapper in history.

It is for this reason that his gradual mainstream approval, beginning in 2002 with The Eminem Show and his impressive screen debut in 8 Mile, has felt so awkward---God sent Eminem to piss the world off, and it’s hard to imagine him ever finding much delight in being part of the status quo. In the months leading up to the November release of Encore it became clear that Em’s days as a shock artist were behind him, and his new record would have to both address and accept his embracement by the mainstream if it was to be as honest and intelligent as its three predecessors.

It does so, but all too briefly and all too early. Encore begins as strongly as any album in his catalogue, with the anthemic “Evil Deeds,” and “Never Enough,” followed by three consecutive show-stoppers that, in addition to acknowledging Em’s new place at the vanguard of mainstream culture, find him exploring uncharted topics, sonic boundaries and lyrical methods with surprising ease.

In “Yellow Brick Road” Eminem tries his hand at genuine story-rapping for the first time, rhyming about his formative days in the slums of Detroit with clarity and skill. It concludes with the album’s most-discussed moment, when Em addresses the infamous Source tape released earlier in the year, admitting plainly “I was wrong.” “Like Toy Soldiers,” over an infectious Kanye-inspired beat, examines his much-publicized beef with Ja Rule and Murder Inc. with grace and smarts, and also reflects on how quickly such petty conflicts can lead to tragedy. On the album’s finest track, “Mosh,” Em envisions himself as the leader of an army of political dissenters, attacking Dubya with stirring but restrained vitriol in what may be his finest single track to date.

Encore peaks six tracks in with “Mosh,” and thereafter suffers one of the worst collapses I’ve ever heard before on any record. The next track, “Puke,” opens aptly enough with fifteen or so seconds of vomiting noises that launch Em into a docile rant against his ex, telling her that the thought of her makes him, you guessed it, want to puke. The chorus, as with most on the album’s last two-thirds, is unbelievably puerile and aggravating, with Em’s colourless whine telling Kim “You don’t know how sick you make me/You make me fucking sick to my stomach.” “My First Single” follows, with a chorus built this time around vulgar non-sequitors and equally pointless belching and farting noises.

The album’s real low-point, though, is its middle section, beginning with the unbearable “Big Weenie,” in which Eminem tells his dissidents, be they FCC censors or rapper adversaries, that they are all (sigh) "big weenies." Elsewhere, first single “Just Lose It” is almost as bad, featuring yet more fart jokes and ADD-influenced lyrics, all behind the worst beat Dre has ever committed to tape.

Bad as they are, none of it comes close to the musically abominable and possibly racist “Ass Like That,” on which Marshall lets the object of his affection know, “You make my pee-pee go da-doing-doing-doing,” between verses where he raps in what must be an attempt at an Arabic accent. These are not songs that will get concerned parents or conservative lobby groups too frazzled, nor will they do anything to reassert Eminem’s self-proclaimed role as Generation Y’s pied piper; they won’t really offend anyone, and outside of 10 year-old boys, they probably won’t appeal to anyone either.

Encore redeems itself slightly near the end, with “Hummingbird,” an obligatory lullaby to his daughter that is nevertheless far more affecting that The Eminem Show’s “Hailie’s Song,” as well as serviceable closer “Curtains Down,” which features Dre’s best production on the album. Both are solid cuts, but cannot erase the damage done by Encore’s disgraceful middle section. Eminem is as entitled to make a bad album as anyone else, and it seems logical that, in an obvious state of transition, this was his time to do it. His dichotomous approach to accepting his new iconoclast status (mixing rousing protest numbers with fart jokes) is tedious and awkward, and is ultimately what makes Encore as bad as it is. And while the best of it is good enough to promise a fruitful and substantive future, the worst of it suggests that in a few years time, Mr. Mathers may be little beyond a slightly intimidating class clown.