Erykah Badu

New Amerykah, Part One (4th World War)

(Motown; 2008)

By Chet Betz | 11 March 2008

The first real song on New Amerykah, Part One: 4th World War is “The Healer.” Over Madlib’s stagger of a chime melody and samples from God only knows (I doubt the Beat Konducta himself remembers) Erykah Badu’s singing creeps, the coming record’s themes sticking to her nails. Those themes? Badu’s own singularity existing as a summation of her influences, artistic empowerment as a bullhorn for politics driven by compassion for people, demolition of self-perpetuated slurs, spirituality made more communal through individualization, missing Dilla, the importance of sonic awesomeness, and: “Hip-hop is bigger than the government / Hip-hop is bigger than my nigga.” The song’s title refers to hip-hop or Badu herself or really it’s both at the same time, that statement owing to the very next track finding Badu metaphysically equating herself with savior, martyr, and also Louis Farrakhan. And to the fact that on New Amerykah there is no longer any distinction to make between Badu and hip-hop. Except that, maybe, Erykah Badu is bigger than hip-hop.

Badu’s made a subtly radical shift in how she’s welding together her performance with the tracks, creating a symbiosis between singer and beat that might be without a complete precedent. It’s a lot like what she’s done in the past, just controlled in a new and exacting way that makes her voice sinew to the bones of these hip-hop grooves. The restraint in the singing and its mixing is remarkable, all while being craftily intertwined through the music’s cadences and punctuation; “The Healer” has a handful of examples, a couple being the way a burst of static pops right before Badu utters the word “programmed” and then when she and what sounds like a sick theremin reach in tandem for an insanely high closing note. Even more blatantly, “Me” ends with a sort of scat exercise where Badu and a sax run hand-in-hand through a complicated melodic line. This is dynamic musical chronology with foreshadowing and double exposures, not just the production responding to Badu or vice versa. The end result’s a long, mutating chain of vocal hooks (perfectly complemented by all manners of multi-tracking and backing) that forms a genetic strand chemically bound to the other half, the beat. Quid pro quo, New Amerykah has a bizarre strength, an evolutionary step away from its genre ancestors.

Aaron Newell calls this freak a “weird mess of an awesome record,” which seems totally right at first but then maybe even a little too derogatory after multiple listens have let it seep in. Badu here handles opulent ambition with funky kid gloves and fierce intelligence, as if in the process of laying down the initial tracks she and her collaborators got absurdly high (Madlib passing around blunts the size of sequoias and telling obscure jokes in his Quasimoto voice) but then when it came time to finish and mix and sequence they all got cold ‘n sober and made tough decisions resulting in a shockingly cogent album. The taut reins even lash down the foibles of some star contributors, ?uestlove treating his poor snare drum to a rare brush caress on “Telephone” while “Twinkle” features—probably contrary to the belief of many a Mars Volta messageboard—the most tasteful and effective application of Omar Rodriguez-Lopez wankery since, well, ever (big props to Sa-Ra’s Shafiq Husayn and Taz Arnold on that count). This is probably what Badu’s on about when she calls the record’s approach “science.”

Clayton Purdom opines that it’s like Badu “jacked the sonic palette of golden era hip-hop and its source material and smelted it all into something strangely relevant and challenging.” Riffing off that thought, it could be said that New Amerykah uses hip-hop as a way of recalling idea-driven, somewhat esoteric soul and funk like Curtis Mayfield’s Curtis (1970), Sly and the Family Stone’s There’s a Riot Goin’ On (1971), and Marvin Gaye’s Here, My Dear (1978) while being simultaneously tighter and more diverse than those records. After the two-part “Me” and the interlude-like (yet cool) “My People” one might be tempted to think the album’s conceptual drive is about to have it peeling rubber and spinning out into episodic eccentricity. Then Karriem Riggins’ gauzy keyboards and warm-as-cocoa kick put a hand up on next single “Soldier.” This is a groove that goes on for miles and its position in the track list makes it an assurance that carries through the rest of the album: ladies and gentlemen, the well that New Amerykah is tapping is proven.

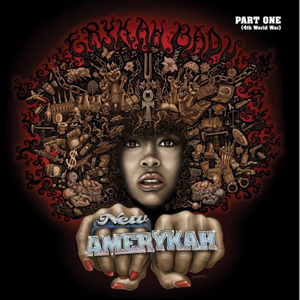

Seriously, one could spend all day finding things to dislike about this record before the album’s sovereign context exposes most grievances as petty niggles that, on a different day, could be considered positives. Like, who needs the extended lounge outro of “Master Teacher”? It doesn’t really do much but contrast past jazzy Badu with new boom-bap Badu, showing how the musical synergy gives a completely different character to the way Badu’s voice and words emerge…oh wait. The initial tastemaker reaction to 9th Wonder-produced “Honey” was understandably muted. “Sure,” they said, “it’ll make a good single but this is a bit too fluff a direction for the Badu we know and love.” New Amerykah is so very far ahead of us, fellas. “Honey” not only appears as a mere bonus track, its preamble connects it back to the consumerist mantras of album intro “Amerykahn Promise.” Badu’s adorable when she winks. Why, the full album title itself looks ridonkulous on paper but when seen on the cover with the different placements and proportions of the text and while listening to the splash ‘n sear of coke-attack “The Cell” into youth-attack “Twinkle” it’s like, “shit, yeah, feeling you on that title, Badu!”

Not content to smooth wrinkles, this same arching context stretches meanings to the extent of their corners. On “Twinkle” an obvious line reading would put Badu at “they don’t know their god” but the Five-Percenter bent of earlier tracks “The Healer” and “Me” could also give that a second shape, “they don’t know they’re god,” smoothly setting up the central question of “Master Teacher”: “What if there were no niggas / Only master teachers now?” This depth exists within songs, too. At face value it would seem Badu’s being broadly situational about getting over “That Hump,” but the wah guitar and deep bass BGV on the hook drip sex, which lends a bit of antagonism to when Badu cries in the middle of the song as a mother who needs a “better house that comes with a spouse,” which in turn serves as a dramatic prelude for the sudden gospel breakdown wherein Badu confesses to her lover as they lay in bed. Then, of course, the slow jam returns. “That Hump” becomes like a Common entendre, one of the good ones. Thank goodness, though, that here there’s no Common or Talib Kweli or any of the suspects one would fear appearing on a Badu record; something this big has no room to be lessened by emcees who are currently thinking too small. Newell, referring to some choice lines from “Me”: “Does she take a dig at herself for having babies with rappers? I think so.”

Yet this whole exemplary record serves up honor to Badu’s peers, most specifically J Dilla and how he represented the essence of hip-hop. The first track proper dedicates itself to him and the final track’s based on a story Dilla told his mother shortly before he died about how he received a call from ODB to take the “white bus” and not the “inviting red bus” once he reached the other side. Beyond Badu being close to Dilla (who produced four tracks on her excellent 2000 LP Mama’s Gun), it’s easy to see how this kind of tale would appeal to her. There’s spiritual mythos (a fork in the afterlife road) slightly twisted by appropriation of distinct cultural elements (getting a phone call from Ol’ Dirty) into something unique. For all of Badu’s ideological and musical unification she’s not doing it in an arrogant way that contradicts or steps outside of the traditions that inform her art, or at least not the good those traditions offer; that’s a big part of why this record is both the most progressive and absolutely accessible release to drop so far in 2008. And talk about context: on “Telephone” a sample of Dilla’s own signature sirens set the scene for his hospital deathbed. No wonder that at song’s end Badu shudders out a quiet “thank…thank you.” This record doesn’t just describe hip-hop as it dreams it, it gratefully wraps itself in the canon that formed it, and it treats that canon very personally.

It’s hard to imagine how Badu could possibly top this first installment but still exciting to think that she’ll be expanding the New Amerykah bigness when later this year she drops Part Two: Return of the Ankh (title’s going to be awesome, right, and if there’s additional auspice it’s in the expectation of at least one Dilla beat). So, yeah, Badu is bigger than hip-hop. Or, perhaps to be more truthful about it, what she’s doing now is bigger than my perspective of hip-hop is—or at least once was. I’ve always felt pretty comfortable parsing hip-hop records, saying, “Here’s the rapping and it is good/bad, here’s the beat and it is good/bad, here are the rhymes and they are good/bad; and the three shall be wed in the name of Holy Concept or lack thereof.” Badu’s elevating and/or altering key characteristics of each member of that trio and then blurring the shit out of the delineations, meaning that the Holy Concept is very present and its name is ringing a little more powerfully than I can handle or take for granted. In every which order I could put it: Badu is people is hip-hop is god is nation, the title of her work grafting her first name into this country’s. So this is the face of New Amerykah. Nearly 1700 words and I still feel like this record’s left me speechless. That’s an epiphany to cherish.