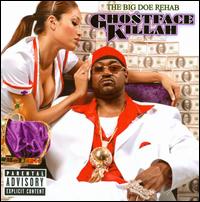

Ghostface Killah

The Big Doe Rehab

(Def Jam; 2007)

By Clayton Purdom | 3 February 2008

Because I heard it too much, because it’s only got a handful of good beats and only a Raekwonful of good guest spots, because I read too often how great it was by clowns who don’t really get Ghostface like I do (scoff now, this is only gonna get worse), and because I find too much pleasure in being a contrarian, I hereby reject Fishscale (2006). Fuck you, too.

Give me instead the circus panoply of More Fish (2006), the smudgy brilliance of Bulletproof Wallets (2001), the nervousness of Ironman (1996) or the autistic Lynchian decade-killer Supreme Clientele (2000). Give me anything, really, but a goony self-caricature of my poet laureate, this Ghostface Killah.

Because this Ghostface Killah — the Ghostface I hear on The Big Doe Rehab — is not the guy who stepped out of the Wu with dazzling charisma and a blunted mic prowess that conflated all that was high-art and low-art about hip-hop into one electric erratic entity. With the Wu and on his first, third, and fourth records that emcee whispered street tales to the stars and boomed the concerns of the infinite down in street language, collapsing pretension and building a playground with the rubble. On Supreme Clientele — his second solo album — these qualities congealed momentarily into a style of absurd opacity and freshness; inasmuch as hip-hop is a platform upon which to restructure the meaning of words it is the most impressive album of its kind ever released. By my timeline, and with my hallmarks, this emcee is a leviathan shooting around the outermost stratosphere of hip-hop greatness for almost a decade (1995-2004). But that rapper is gone, and in his place is a dude that looks like Ghostface and sounds like Ghostface but resolutely is not Ghostface — at least, not the one I described above. I’m willing to be alone here: Ghostface has fallen off, completely. What’s strange and upsetting about this is that it happened a few years ago and none of us noticed, because like theatergoers swept up in a standing ovation we were too enthused with being enthused to question the performance.

Now, a lot of what I’ve just said contradicts shit I’ve said before, in print and in person. So, I’ll say now: I recant. Anytime I ticked Ghost off as one of the best emcees working, I was wrong. His last three records, on their own and to someone who doesn’t really care about such things, are okay, I guess, but even so these are for reasons having little to do with Ghostface: generally great production, a cabal of great guests to pull from, balanced sequencing and some deft PR moves that’ve kept him on the cool side of things. But I don’t really care about PR, guest spots, album flow. Not with Ghostface. This artist means too much but has since hollowed. I have been slamming my face against the reality that I don’t like this emcee anymore since Fishscale, which had, yes, “The Champ” and “Underwater” and some sharp darts but which signaled the death of his old wild furious style. I knew it then, I just didn’t let myself know it. I was not ready.

The path here was not smooth. Upon first hearing The Big Doe Rehab I felt total apathy, then mild distaste, and then finally a strange and embarrassingly uncritical thing occurred: On the fourth or so run-through I decided I liked it. I told myself this was the case. It wasn’t a classic, I knew, but I allowed that the beats weren’t exactly attuned toward my tastes and let the record roll. It was a “fun” record, if slightly off-point. If I had reviewed it upon its December release it may’ve netted a 70% from Cokemachineglow, but by this point in the new year I’d be back where I started, carefully avoiding giving it any thought, and feeling uneasy when I did. Something felt wrong about this reaction, but my gut was (as always) correct, if I listened to my gut. I was confused, caught up in the other reviews and the fact that it was Ghostface, just as I had been since Fishscale leaked and it never clicked for me no matter how many times I let it bang from my speakers.

So my positions have wavered wildly, but I am now at the root. What I’m saying right now is not a matter of new interpretation. I am not interpreting these records differently than you; I am listening to them clearly, and you are not. The light of sanctity that has been cast almost universally on Ghostface recently isn’t unlike the critical favor Bob Dylan currently enjoys. We all just kinda assume that “Bob Dylan’s on point again!” because he doesn’t suck, and we all just kinda assume that Ghostface is putting out good records because nobody is telling us that he isn’t — except for me, starting right now. So, I mean, yes, Time Out of Mind (1997) was a classic record. Bob Dylan jumped back on point right then. But, I mean, is fucking Modern Times (2006) a five-star effort? Of course not. We all know this. The same is true of Ghostface Killah. We are clinging to a decade-old triumph. We are not listening to his records like we care about them. So I’m saying now: Other critics, get ahold of yourselves. Put your goddamn critic pants on. The hard line on Ghostface right now — mainly capitulated by the man himself, but regurgitated tirelessly by the critical establishment — is that his mic style has evolved from the obtuse wordplay of early releases through a good if unprofitable stint at Method Man style pop-rap crossover into this newest and best incarnation as an elder statesman and consummate storyteller.

This is horseshit. Ghostface has been a storyteller through and through since his earliest Wu rhymes. Check, for example, the legendary final verse of Forever’s (1997) “Impossible,” or the dense neighborhood portrait narrated in the first verse of “260,” off Ironman. The first of these needs no further commentary. The second could only loosely be considered a story, but what of it is being told is remarkable: Ghost flits between characters, inhabiting voices, drops Five Percent references alongside extraterrestrial and fast food ones, pulls that “Peace, Keana” moment right out of the explosion of words he’s created as a breath of air before letting Raekwon take the story home, the stage set so comprehensively. This whole “transformation into a storyteller” bit is a lie; his career is built on an old reputation for shaggy dog stories, bildungsroman, anecdotal confessionals, and noir capers. Calling him a storyteller was once the barest description of what he did; today, it is comprehensive.

And, at this point, charitable. Flashes of the old dynamo lingered on the last two records. There was fun to be had, fleetingly. But on The Big Doe Rehab the stories aren’t good, and they’re not even being told well. Let’s be nice and start at the top. The obvious best track here is “Yolanda’s House,” wherein Ghost, I dunno, fucks some girl and Method Man fucks some other girl too and there’s some blow and cops or whatever. The point is not the story, the point is the beat, which is a fairly swooning little banger, and the rhymes, which melt effortlessly from Meth and Rae after a rote laundry list of clichés from Ghost. We’ll just use this rap as an example, but the encyclopedic use of lowbrow reference points and the singular grasp of microscopic detail are entirely lacking on Ghost’s verse here. The best line is the bit about Yolanda making fish sticks; beyond that, weed makes people paranoid, Ghostface has a penis, Porky’s Revenge is a movie, etc. This has the scope and tonal complexity of an Xzibit rap. As on Ghost’s last two records the sense of narrative urgency is fabricated by just running places constantly. Here he’s “jetting through bushes and backyards” and later “jetting up the steps,” his verb choice even shorn of invention. It bears mentioning that back when he was in touch with the celestial, inspiration oozing from every word he spit, he realized the limitations of this device and so just called the fucking track “Run.” It was, if you’ll recall, incendiary.

We have no such bangers here, of course, just “Yolanda’s House” and a couple hot mic tosses on “Shakey Dog Starring Lolita” (thanks again, Raekwon) and “Killa Lipstick” (peace to Masta). Beyond that, we have the failed potential of “Toney Sigel,” all chintzy guitars and Beanie phoning one in, garish lead single “We Celebrate” (which contains one of Ghostface’s very worst lines: “If you fat, I might take one for the team / But I gotta get drunk first / Know what I mean?” to which I’m just like, yes, I get what you mean, it was pretty straightforward), the breathtakingly ill-advised attempt at zaniness “White Linen Affair,” and so on. Even the bright lovely beat for “Slow Down” feels squandered here — the guy who finished albums with “All That I’ve Got Is You” (kinda) and “Love” takes this wistful wonder as an excuse to just outline all the great shit he owns. What moving sentiment! What utter dross!

Really, the sad emptiness of these raps needs little explication from me. I can merely set them up near older counterparts and watch them crumble. Check the breathtakingly cocksure “bugling” imagery of ”Black Jesus” and the tired recitation of decade-old slang on ”Rec Room Therapy”. One verse cannot contain its enthusiasm to a single image; the other barely musters a “must stay paid.” Or witness if you dare the Heironymus Bosch-like sexual Armageddon of his verse on “The Projects,” the phrase “ping-pong pussy” conjuring images more terrifying than any girls sharing any poo in a cup, and then slug through ”Supa GFK,” wherein Ghost achieves Snoop levels of faux-pimp self-parody. I’m not reviewing 8 Diagrams, but Ghost’s raps in that vein are further evidence of an intellectual divorce. This verse begins with promising if jumbled imagery before devolving into the type of spell-along gymnastics that impress Talib Kweli fans. (And need I link to examples of better Wu raps?)

Ghostface, then, is adrift. Wanderlust drew him from the Wu but now, unable to gain the mainstream acceptance he wanted, he has lost entirely his sense of humor, his artistry, his unbearable passion. He has lost everything that made his venom poisonous and his wit beguiling. He is a goony, leering shill. He peddles his skateboards, his doll, his book. He sees you — yes, you, CMG reader — as an inadequate fan. He wants the pop airwaves, fuck your messageboard enthusiasm. He doesn’t rap on “Life Changes.” He doesn’t ask why the sky’s blue; he doesn’t care why water’s wet. The flow remains sound but the artist is a liar.