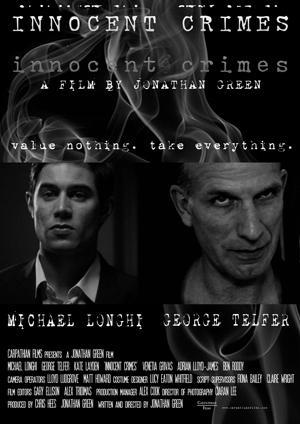

Greg Harwood

Innocent Crimes OST

(Unreleased; 2010)

By George Bass | 27 October 2010

Bucks composer Greg Harwood returns with Innocent Crimes: his second set for an independent feature, and the second time he’s cooked up batches of synthesised strings to ferry us through Britain’s upper underbelly. The underbelly in Crimes is a strange one; a parallel London where you can still smoke in pubs, there’s no burglar alarms and accountants still have jobs. One of these accountants is Farley Chambers, a repressed young shiny-arse who gets seduced by dodgy older company. This isn’t the start of some boy-meets-cougar comedy, though—the older company here is a wizened old housebreaker who leads Farley on a spree round the capital. Harwood colours them in with cues which flit between doom, deep thought, and redemption, and the actor playing Farley, Michael Longhi, follows suit accordingly. He’s got his hangdog chops down to a T—the permanent hunch, the first-time cigarette cough, the hundred-mile-away fall guy tag. Will he keep on burgling until his mentor abandons him? Will he take a deep breath and realise that his mum, disturbing habit of spoonfeeding him aside, was right?

If the story isn’t comfortable exploring the same themes as last year’s indie sleeper Breathe, then Harwood is: he’s ostensibly reworked his cues from that film, and spruced them to big distributor quality. And while the composer remodels his own work, the film plagiarises something a little older: Christopher Nolan’s Following, another black and white micro-budgeter about underachievers lured into the art of housebreaking. However, cameo appearance not included, Harwood gets a lot more involved in Innocent Crimes than David Julyan did in that film. He even deviates once or twice from string work altogether into dapper jazz, such as on “Meaner Business Still” where he does Wire-credits things with double bass. This ident helps set up the smoky mood as the accountant walks meekly into a private bar. It’s here where Farley links up with Charlie—Charles Wells; a man who talks in more riddles than Tom Hardy, and the best gentleman thief in town.

Mr. Wells is a burglar, but one with a peculiar philosophy: only steal items you deem impractical, leaving homeowners to return and face “a state of reanalysis.” In case you’re wondering, he also wears a waistcoat and cravat, keeps his smokes in a pewter cigarette case, and talks like Liam Neeson in Batman Begins. However, he helps Farley grow balls, and Harwood’s work accompanies the double-act as the young half goes on a journey. On the whole, the journey is smooth: “The Refuge of the Innocent” is perfect for those self-actualisation scenes in Farley’s attic bedroom, and you get to taste the bourbon on “The First House Break,” where scratchy fifties blues covers Mr. Wells as he jemmies his way into a townhouse. It establishes the flair and restraint you’d expect from a seasoned cat burglar, and Harwood is as careful as his antagonist, both wearing silk to reduce noise.

Silk aside, the more dominant gist of the score—its clipped symphonics and frisky picks—could be the stuff of a thousand finance ads, with Harwood playing the Junior Manager whose best pens stay chained to his desk. It’s a deft but repetitive set he’s put out at almost forty minutes, with some of the rousing moments hitting the more bizarre parts of the film, such as the playing of the soaring title track as Wells dives out of a window, still in shaving foam. The cryptic piano and clarinet intrigue on pieces such as “The Seduction of the Night” could pass for Eric Serra’s work on the Leon OST (1994), while other moments—“The Knowledge of the Trap”‘s tense drone, for example—seek out the more nervy scenes, like the two chums’ revenge-burgling of Farley’s clown of a boss. You get the feeling that writer/director Jonathan Green wanted to stick it to the bankers hard here, and Harwood’s job was to wrap up the weaponry, making sure it all looked respectable. He does a good job, particularly on the longer suites such as “Escaping the Truth,” where piano droplets and morbid harps steer the film through its slasher-mindfuck twist. This then gets countered by the lighter clips such as “The Cello Player,” which successfully introduces, through feathery piano, the girl with the plummiest accent in cinema history. Elizabeth II, you can eat your heart out. Then wipe your mouth with a Pima cotton napkin.

There are two things that strike you about the eighteen tracks on Innocent Crimes. One is Harwood’s well-observed study of city rich districts, and his responding with the kind of inoffensive music that would light up the mock Tudors of Mayfair. The other is his increased punching power as a composer—though still relying mostly on layering, he can now create themes and redress them to suit the action of the first crucial edits. The sound he’s created for this film isn’t exactly grabby, but when Harwood is asked to make a point he can do it, like “The Herald of Change”‘s burning-your-clothes-in-a-bin-scene or the dark finale of “Old Habits Die Hard.” His brand of twisty-turny drama cues means he must now be The Man to hire if you need music for patriarchal criminals, and his composition here does an accurate job of mimicking every closet nerd’s worst nightmare (except the one about being late for your exams without having revised, and being naked).