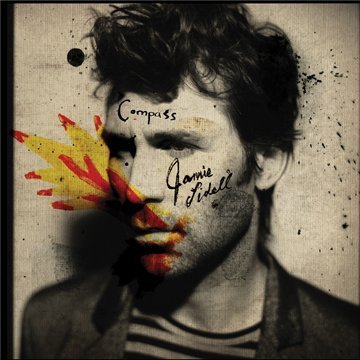

Jamie Lidell

Compass

(Warp; 2010)

By Andrew Hall | 15 July 2010

Since discovering his singing voice and outgrowing his IDM roots, Jamie Lidell has struggled to balance his futuristic pop and retro-Stax/Motown aspirations—in essence a push-and-pull between his roles as producer and singer/performer. Multiply (2005) came off as much neo-soul as Jamiroquai, while Jim (2008), with its even more straightforward revivalism, reigned in the experimental edges and delivered several immediate hook-laden pop songs that both substantially expanded his audience and prompted derisive nicknames like Jamie Winehouse. While Lidell may be an eccentric, and a strange thing to witness in person, his recorded output had simultaneously become more approachable and less engaging; Jim‘s three minute pop songs, more novel because they were being sung by a thirty-six year old British man in 2008 than because of the music itself, sounded utterly joyous but ultimately felt rote.

Compass sounds like it was deliberately made to shake this criticism. Compared to its predecessors it’s a massive, fractured thing, the production once again imaginative and out-there. He enlists a number of major collaborators—Feist on a few tracks, most of Grizzly Bear sans Ed Droste or Daniel Rossen appears in some capacity, as does Wilco’s Pat Sansone—but none seems to shape the material more than Beck, who gets a coproducer’s credit here. Rather than a simple showcase of Lidell’s voice, this record embraces chaos much like Spoon’s Transference did, but it doesn’t so much strip down and sound unfinished in places as much as it simply diversifies. It throws idea after idea out, often within the space of a single song, and though the finished product is overlong, much of the material both validates Lidell as both singer and producer, revealing his damaged headspace as one far more interesting than one built entirely on stability.

Lidell makes this clear from the outset. “Completely Exposed” begins with a vocal approximation of of Tom Waits-ish junkyard percussion that repeats throughout much of the song, and the vocal layers deliver the song’s best riff—not one of the vocal lines is presented cleanly, and each is in its own way wounded or subdued. The percussion in the bridge most closely resembles Bangladesh’s kick-snare work for Lil Wane on “A Milli” and the finished product has an undeniable propulsion. “Your Sweet Boom” sounds like it could be utterly conventional, and the soul melodies are there, but they’re mixed quietly and sung in a whimper hard-panned to the right. In every way the production serves to emphasize the vulnerability of Lidell-as-narrator. The title track sounds like Lidell’s take on the balearic revival, perhaps recalling a more sophisticated version of jj’s basic aesthetics than anything else, and “Big Drift” sees him simultaneously take on Grizzly Bear’s most cerebral work and the vocal interplay that suddenly made Dirty Projectors an event band last year, perhaps at least partially a consequence of both Christophers Taylor and Bear’s playing on the song.

When the album reaches its songs that exhibit the confidence on display in his earlier work, it’s deliberately overtaken by the dense, layered production. “She Needs Me” refuses to deliver its gorgeous chorus until three minutes in and “I Wanna Be Your Telephone”‘s best point of entry is probably all the time Lidell spends making noises that sound vaguely like machinery. “The Ring” sees him work through funk-gospel and “You Are Waking” opens as AM radio fare, then turns violently aggressive with screeching noise and relentless percussion, with the one-two punch brought on by their sequencing proving hugely effective at drawing forth something almost apocalyptic.

If there’s one major complaint to be made, it’s that Compass is simply overlong. These fourteen songs are proof that there is far more longevity in Lidell’s work, even if at over fifty minutes too many moments seem frivolous or forgettable compared to the striking highs. His previous two outings, whatever their own problems, at least kept things brief, showcasing the singer-songwriter’s strengths and getting the hell out. Clearly that wouldn’t have meshed with this album’s overall aesthetic, but some pruning would have turned this from a record that’s quite good—and still no doubt his best since Multiply— into one of the year’s best.