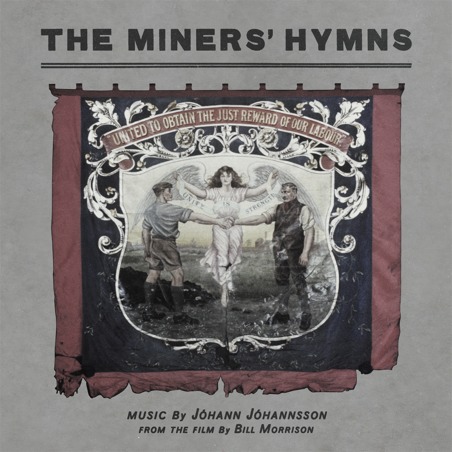

Jóhann Jóhannsson

The Miners’ Hymns OST

(Fat Cat; 2011)

By Conrad Amenta | 7 January 2013

I’m late to the party on this one. Jóhann Jóhannsson’s astonishing, beautiful, politically timely and historically literate soundtrack to Bill Morrison’s film of selfsame importance is the kind of release one wishes they’d become aware of, you know, when it came out, which in this case was mid-2011. Why review it now? Tripped over while scrolling through an iTunes library of forgotten promos, it’s since nestled its way into my listening circuit, wedged itself firmly in my brainpan. Part of me thinks I’m just an ambient fan talking about a nice bit of instrumental brass filtered through electronics. Another thinks this record has only increased in relevance since its release and so needs to be revisited.

Judged entirely in a vacuum, the soundtrack is dismissed as dour—it was, rather flippantly, reviewed by another publication with which you’re probably familiar as something that “will not make a stellar accompaniment to your next barbecue.” That review goes on to talk about the album entirely on the basis of its aesthetics: six-pieces arranged for a sixteen-piece brass ensemble, recorded in a cathedral, cycling ethereal melody through space. Far from the bright tonal presence one might be accustomed to when listening to brass, these tracks are distant, obscured, and faded. Listening to the album without first reading the one-sheet, I assumed that Jóhannsson was working with field recordings or historical documents. Its arrangements build, reminiscent of ambient work of Tom Recchion and William Basinski, and are deceptively inhuman and precise. These are very deliberate choices.

The Miners’ Hymns shouldn’t be listened to in a vacuum if it’s to be really appreciated. The key is to think of Jóhannsson’s use of aesthetic as a central rather than peripheral component for historical contrast. Here aesthetic is not merely a stylistic flourish—something to superficially distinguish product x from y—but an attempt to use the listener’s temporal associations to comment on the subject of labor and consumption. The film around which this soundtrack is built is a documentary which presents wordless archival footage. “Focusing on the Durham coalfield located in northeastern England, it depicts the hardship of pit work, the role of Trade Unions in organizing and fighting for workers’ rights, the years of increased mechanization and the annual Miners’ Gala in Durham,” reads the film’s synopsis. It’s not an excoriation or a celebration of one of the dirtiest, most dangerous vocations in modern history. There is no narrator to frame the footage with an argument or an ideology; the conditions are presented as fact. And so Jóhannsson’s soundtrack does most of the emotional heavy lifting, establishing sentiment and tone. We rely on the romantic, sweeping gestures of Jóhannsson’s arrangements and the haunted, anachronistic sounds of his production to align the subject matter with our contemporary understanding of these same issues. A transmission from what is literally a forgotten period in our history, Jóhannsson’s work captures the perseverance and the desperation of the miners, literally glorifying them as they too glorified their work with music, but then dapples that light through effects to fade that glory.

What makes the album interesting today is how loaded a time it is to be talking about organized labor, energy politics, working conditions, and how music is used to both celebrate and distinguish local culture. Simply by lifting archival footage and presenting it again, Morrison reminds us of how hard previous generations fought for rights that are slowly but inexorably being degraded today. Jóhannsson’s music serves this mission well; even the titles of the pieces—titles like “Industrial and Provident, We Unite to Assist Each Other,” and “The Cause of Labour is the Hope of the World”—are so loaded today as to prevent their utterance by anyone who hopes to be taken seriously. Likewise, Jóhannsson presents the triumphal arrangements as something that struggles to travel distances to the listener’s ear—that swims upward through heavy water towards air, suffocating to be heard. The music is beautiful, to be sure, but it has a constrained beauty that is entirely the point. At a time when the politics of labor is at the forefront of our national dialogue, one half of the equation is marginalized to the point of silence.

Here in Ontario, Canada, where my provincial government struggles to wrestle with deficits it created with one of the lowest corporate tax rates in North America, health care providers and public school teachers are having new contracts unilaterally imposed on them and their collective bargaining rights removed. Being Canadian I know less about what’s happening in America, though I’ve read about “Right-to-Work” legislation in organized labour’s back yard of Michigan, and the elimination of collective bargaining in Ohio and elsewhere. What we accept as the new reality of globalized competition today, like this album and film, shouldn’t be viewed in isolation, but as distinct points in a long dialogue around the rights of the individual and the collective. Jóhann Jóhannsson’s soundtrack and Bill Morrison’s film succeed in creating a useful contrast to better understand just what we’ve begun to lose.