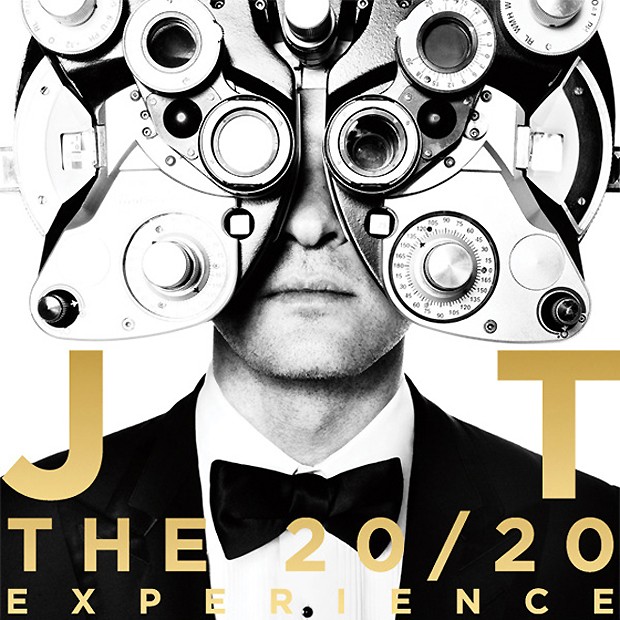

Justin Timberlake

The 20/20 Experience

(Jive; 2013)

By Clayton Purdom | 1 May 2013

A note, to begin, on the outros. Because they’re where this album lives or dies, at least in the public consciousness. I’m a fan, for reasons I’ll get to later, but the point is that this is the dirty secret of Justin Timberlake’s career: we never quite think he can pull this shit off. And we love that about him, for the most part. It’s not even that he started off in a boy band, which is a tired narrative but certainly part of the reason why we balk at the eight-minute tracks here. It’s just that everything he does seems like it’s the most ambitious thing he’s ever done, even if it isn’t. Celebrity (2001) was a concept album; Futuresex (2006) was a concept album; Justified (2002) was probably more high-minded than any of it, a sort of doctoral thesis on Virginia Beach’s influence on milennial pop. Justified posited “hip pop” as not a term to spit disdainfully in mid-album Talib Kweli skits but the natural evolution of hip-hop on its path toward global assimilation.

It’s impossible to overstate the importance of Timbaland to this narrative arc. With “Cry Me A River” he found a melancholy sweet spot that simultaneously played off of and expanded the public perception of Justin Timberlake, Star, and in its aftermath Justin Timberlake stepped into a role which had previously been held by Missy Elliot and, before that, Aaliyah. Timbaland always worked best behind someone else (with Magoo, he briefly tried a sidekick); Timberlake always wanted, well, a good producer (shots fired @ Wade Robson). On “River” they locked eyes, on Futuresex they fell in love, and on The 20/20 Experience they make a beautiful baby, perfectly of both of them. 20/20 was reportedly recorded in a couple weeks, and even as produced as it sounds this “couple weeks” theory holds water. The whole thing has the feel of a creative burst. When Timberlake coos that his spaceship coupe only has room for two, don’t get your hopes up: that’s Timbaland beat-boxing in the passenger seat.

At a svelte ten tracks—which is a glorious, almost holy quantity for an R&B album—there is only room for both artists at their absolute best. At first, you will be forgiven for thinking the album Timbaland’s triumph. In sheer sonic magnificence, the album rivals Watch the Throne (2011), but its aims are warmer, more human. You are being asked, in other words, to dance, but Timbaland will not make that unagreeable. He will, right at the outset, pop you with gigantic D’Angelo neo-soul (“Pusher Love Girl”), then with glorious James Brown disco (“Suit & Tie”), then, on “Don’t Hold the Wall,” he will slyly sound a lot like circa-2003 Timbaland, and it will sound incredible; it’s almost like Timbaland is making a case for his own greatness by setting his own musical signatures into a canonical context (check the alien percussion switch-ups in the fourth measures, the minor-key found sound samples). The result would be encyclopedia-thumbing pastiche if it weren’t all so carefully curated, and if the production wasn’t so intricately, lavishly produced that as each track stretches into the fifth or sixth or eighth minute it was not still revealing permutations, secrets, strange little surprises.

What holds all of this disparate influence-spotting together (we hear 2010 Kanye or primo Aaliyah on “Tunnel Vision,” 2001 Bjork or actualized Imogen Heap on “Blue Ocean Floor,” etc.), is, of course, our endearing host from Memphis, Tennessee. The record’s obsession with JT’s wifey has been well-parsed elsewhere, but it sounds like bona-fide inspiration and it unifies the record with gusto. Timberlake’s no Marvin Gaye, so it’s perfect that his Janis Hunter is big sister from 7th Heaven. Then, vocally, JT’s always been criticised for the thinness with which he tries to loverman croon, but as big as these arrangements get, they leave plenty of room for him to operate. Sonic elements are chosen with care: of all the components on “Strawberry Bubblegum,” for example, the majority is careful ornamentation. The beat itself is almost austere. (Conversely, “Mirrors” is the album’s sole misstep for this exact reason. It’s an arena-rock song on a nightclub album—but, oh wait, damn, here comes the outro, nightclub death swoon resplendent). More importantly, though, is the way Timberlake finds the pocket on each of these grooves such that that thinness doesn’t matter: the kid is rapping in honey-coated melodies. After that opening on “Suit & Tie,” which is just pretty much Timbaland farting, Timberlake locks into the 2 and 4 and makes the most of every drop the beat provides him like he’s fucking OJ Da Juiceman. So ably does he keep finding new entry points that, when Jiggaman shows up on his own switched-up beat, he sounds dumpy and out-of-sorts, struggling to catch up.

The Jiggaman should not have touched the mic, is what I’m getting at. Really, the only rappers that have managed to guest alongside Timberlake admirably were Malice and T.I., dudes who sort of specialize in finding room for themselves. Making Hova sound like a tubby forty-year-old trying to do a layup was probably not the idea when they locked him into the first single, but it does prove the point here: that there is not room for other people when Tim and Tim are operating. The triumph across the ten tracks here is that of a hip-hop producer and a pop star merging their visions into something that is both completely wonderful and also completely non-revolutionary. It is a paean to the glories of listenability. What we hear in the outros, then, is their creators simply enjoying this. It is them holding on, unwilling to relent, whether it’s the sanguine understated half-minute that closes “That Girl” or the breathless burnout of “Tunnel Vision,” the sly metamorphosis of “Strawberry Bubblegum” or a Lionel Richie lullabye on “Let the Groove Get In.” On the outros we hear something rare in pop music these days: musicians enjoying themselves. We are invited to, too.