Kanye West

My Beautiful Dark Twisted Fantasy

(Def Jam; 2010)

By Clayton Purdom & Lindsay Zoladz | 20 November 2010

Kanye West had to do him; and lo and behold, he has. My Beautiful Dark Twisted Fantasy is the most cohesive and assured record in mainstream hip-hop since Jay-Z sketched his Blueprint (2001). But even within that tradition, its lineage is weirder and more unexpected: its gigantic-yet-hermetic orchestral narratives recall OK Computer (1997); its soulful, peak-and-valley pacing, full of wonky guitar interludes and maximalist freakouts, feels like There’s a Riot Going On (1971) or Curtis (1970); its ability to figure a bunch of personalities into one cohesive vision recalls the grandiose pop politics of Rumours (1977). No wonder Rolling Stone dropped a perfect score on it—in order to make his canonical record Kanye had to dodge hip-hop’s self-aggrandizing influence and delve into the epic myopia of ’70s soul and classic rock. That it does all this while still being rigidly, unabashedly hip-hop narrows its direct precedents to one record: that is, the masterwork Aquemini (1998).

But where point zero for Andre and Big Boi was their artistic communion, Kanye’s is both simpler and shiftier. Kanye, like we’re saying, is doing Kanye. At last, he proves up to the challenge. In the past two years he gave up a portion of his self-image, took the fish-stick jokes head-on, realized not just that people hate him but why they do, and, lastly and most importantly, agreed with them. Off with the king’s head, then.

In this context 808s & Heartbreak (2008) feels even more like a crisis of identity than it did initially. Who can argue, now, that it doesn’t sound two-dimensional and slight? Kanye’s melancholy was acted out in a vacuum. It felt sterile, taxidermic, the spectacle of Melancholy put on display like a museum piece. At best, it found triumph in unexpected places, like the stupid sublimity of “RoboCop.” At worst, it was the album-length equivalent of the sputtering “I’m cold / I’m cold / I’m cold” at the beginning of “See You in My Nightmare.” Either way, it was his heartbreak, but for Ye and for us, it was ultimately without catharsis, ending as cold as it began.

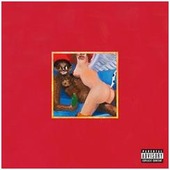

That phoenix he’s fucking on the cover of Fantasy (again: Kanye doing Kanye) is the first clue that this is meant as a resurrection, from scandal as much as from the inarticulate dead end that was 808s & Heartbreak. His melancholic impulses are collapsed with his triumphalist ones, and the resulting duality is revelatory—mostly, it seems, to Kanye himself. Both here and throughout his string of G.O.O.D. Fridays releases, he marries the long-form posse cut of Late Registration (2006) triumphs “Gone” and “We Major” with something new. It is the melancholy of its predecessor but flipped in its details to something angry, like the ominous sweep that re-introduces the beat on opener “Dark Fantasy,” or the martial bass drum, suggesting a sort of Caligulan debauchery, on “POWER.” Sadness and glory ebb together, utterly twinned. Baleful horns gird tough raps and get-it hooks on “All of the Lights”; Hova confesses a naked desire for love on the otherwise giddy “”Monster”; on “Blame Game,” a Chris Rock monologue plays out as tragedy. Indeed, his guests here are all subsumed by his vision, his influences treated as subject to his emotions. Pusha’s lovely closing couplet on “Runaway” might sound like shit talk on a Clipse record; here, amidst black-swan strings, he sounds like he just glimpsed infinity and came back terrified.

But while his superlative skill as a producer has succeeded in doing the impossible—making a Thornton brother sound vulnerable—the most quantum step forward here comes from Kanye as an emcee. Vaulting past the Chicago-leaning conscious-rap of his early career, and past the sharp, lewd wit he debuted in 2008 and 2009, on Fantasy Kanye at last perfects a style that is truly his own. Less eager to please, and more substantial in his message and vision, he packs verses with spit-take punchlines and acidic ruminations on race, often simultaneously: “I treat the cash like the government treats AIDS / I won’t be satisfied till all my niggas get it.” He has taken piecemeal the parts he likes from his favorite emcees: buoyant politics from Common Sense and Q-Tip, generous use of blank space from Jay-Z and Murda Ma$e, freewheeling lasciviousness from Pusha and Weezy. And then he has channeled this flow into song-length conceptual arcs: the red-eyed freakout “All of the Lights,” the cackling fuck-you of “So Appalled,” or, most dazzlingly, the celestial braggadocio of “Devil in a New Dress.” His lyrical clarity recalls, again, Andre 3000; yet his submission of private affairs to public discrimination recalls no one so much as 2pac.

Which is, then, what makes My Beautiful Dark Twisted Fantasy what it is: our perception of its author. Over the past few years, most conversations about Kanye have turned away from his music, propagating instead a stubbornly persistent notion that he’s nothing more than a broken silhouette of Internet memes, Twitter koans, and public temper tantrums—the definitive celebrity of a particularly substance-less moment in pop culture. But My Beautiful Dark Twisted Fantasy is defiantly substantive; it’s not (despite what its fourth-grader art project title implies) simply Ye’s assertion of self. It’s the large-scale greatness of mainstream art played out in 2010: not so much a snapshot of a moment as a meticulously sketched plot to break out of it. Because “lost in this plastic life / let’s break out of this fake-ass party” is a sentiment utterly un-meme-able.

And totally universal. What’s strange is how good pop’s biggest asshole has suddenly become at sharing things, how everything—the passion, nihilism, self-loathing, and fury—feels as much his as it is ours. It’s a sprawling monument to wholeness towering over an artistically and emotionally fragmented landscape. It’s Kanye, like we said, doing him: a circuit at last complete.