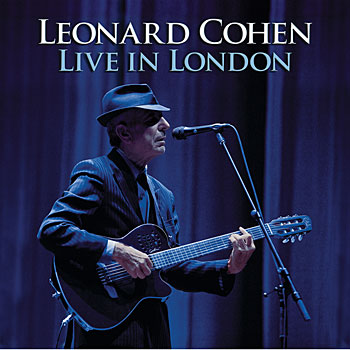

Leonard Cohen

Live in London

(Sony/Columbia; 2009)

By Joel Elliott | 1 May 2009

For starters, rather than listening to the CD you should just go out and buy the DVD. The 74-year old grins throughout like a child, constantly taking his hat off and bowing like a beggar being offered a hot meal and a place to sleep. “It’s wonderful to be gathered here on just the other side of intimacy,” he opens, as if this was just the warm-up for the after-show. You get the feeling Cohen could fade completely into oblivion tomorrow and he’d die happy; a recent Globe and Mail profile described him as a Canadian icon who “dances in our heads mostly unseen, like a beautiful idea.” And this humble opening comes just before “The Future,” a song of immeasurable cruelty. It’s just the first of numerous contradictions that the live document spanning four decades of music musters up.

Sometimes the humility can be overwhelming. Cohen’s constantly calling out the names of his soloists, even after he’s introduced them five times. Maybe he’s trying to give them as much publicity as possible (it worked, I hardly have to consult a one-sheet now) but its effect is to constantly rob the listener of whatever immersion the music could offer on its own and draw too much attention to their status as “session musicians.” A similar awkwardness is found in Cohen’s occasional reciting of lyrics from a song before he sings it. If you’re a fan you’re probably aware of this tendency to over-interpret every single tic and gesture he makes. Remember those old NFB docs from before Cohen had even started making music, where in one scene a panel of intimidating literary critics grilled him on his philosophy and in the next he’s in the bath and sleeping? Even then, he was central to our country’s longing for a kind of kitchen-table warmth, for someone who practices real life with sagacity.

But the reason why a live set comprising his entire career is daunting is the discrepancy between his older and newer material. While many folk singers who started out in the ’60s wound up awkwardly embracing synthesizers and modern production in the ’80s, Cohen embraced it completely and semi-ironically on I’m Your Man (1988), an album which can be found almost in its entirety strewn throughout this two-disc set. The approach didn’t work for most folkies, who thought they could just give their usual songs a different backing, but it worked at least partially for Cohen, who entered the second phase of his career with apocalyptic songs that seemed to comment on the technology itself. It also worked because his lyrics have always had a way of transcending the music behind them, and even the karaoke arrangements can sometimes be forgiven when they back such beautiful songs (at the beginning of “Tower of Song” he wryly refers to the synthesizer: “it goes by itself”). But that doesn’t mean that a masterpiece like Songs of Love and Hate (1971) doesn’t stand out chiefly because it mixes his most harrowing and dense lyrics with tortured vocals and orchestral arrangements. This is what has really been missing in the last few decades: the music is still occasionally dark, often tender and beautiful, and sometimes hilarious, but it rarely captures that emotional core. Sadly, there’s no songs from that album on here, not even “Famous Blue Raincoat.”

But perhaps I should get to what is. Cohen manages to find the happy (and probably most obvious) middle ground between his spare origins and the sheen of his later work with light, jazzy instrumentation, with the songs stretched out to allow for several solos and interludes. It’s not really as bad as it sounds: Javier Mas’ work on the archilaud (like a classical 12-string guitar crossed with a lute) and Dino Soldo’s various wind instruments add a lot of diversity and even highlight the sometimes understated quality of Cohen’s songwriting, particularly on “Who By Fire.” The band is also wise enough to back off on “Suzanne,” which somehow manages to be just as euphoric as the original, yet that much more enthralling coming from Cohen’s increasingly cracked voice. And I’ve already expounded on the virtues of the brilliant seven-minute version of “Hallelujah.”

Apart from these, most of the material is presented as you might expect it to be. Most of the selections from I’m Your Man benefit from their arrangements, in particular “Tower of Song” and “Take this Waltz.” Perhaps because these songs are the only overlap between his brilliant songwriting (rather than just beautiful lyrics as on his most recent work) and his more contemporary production, and so are fitting for a warmer re-arrangement—except for “Ain’t No Cure for Love,” which I always suspected was a really dark joke coming before the AIDS-crisis doomsday romance of “Everybody Knows” on the album. Here the two tracks are separated by an almost unrecognizable “Bird on the Wire,” so whatever.

Despite the arguable quality of some of the songs, there’s no accounting for how incredible it is to watch Cohen still performing. He’s far from irrelevant even now; Book of Longing (2006) is one of his strongest poetry collections, including some startling and immediate self-portraits that have inadvertently launched his side-career as visual artist in his septuagenarian years. To say that Cohen’s a shadow of his former self, well, he’d probably take it as a compliment.