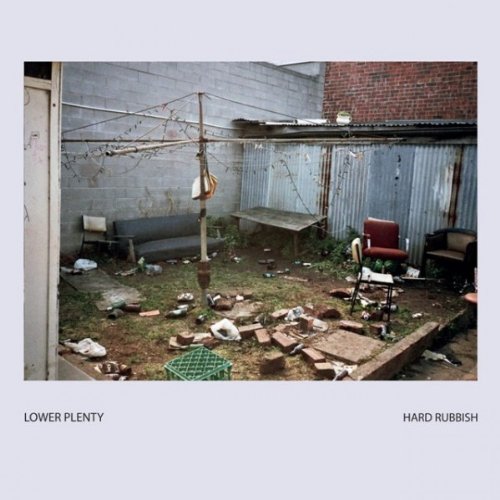

Lower Plenty

Hard Rubbish

(Fire; 2013)

By Chet Betz | 9 May 2013

Droll, casual, immaculate, Melbourne outfit Lower Plenty’s debut Hard Rubbish seems to base its paradigm on oxymorons, to the extent that it’d probably be an oxymoron to call the record oxymoronical. The issue is that it’s both an incredibly easy and impossibly difficult album to categorize and define, which is probably the aim of a lot of musicians when it comes to how they want to be received—but where most strive and fail, Lower Plenty achieve this quality rather effortlessly, organically. I’m tempted to invoke Nick Drake comparisons when hearing that equal parts quaint/melancholic guitar figure that slowly drives “Friends Wait, “ but singer Al Montfort (or Jensen Tjhung, not sure which) croaks more than croons, and yet if it’s a croak it’s a croon of a croak. Call it a croan. Sarah Heyward also contributes a lot of vocals to the record and somehow does so rather atonally while still sweet and neatly on pitch; her percussion loops (from what the band calls a “psych station”) and Daniel Twomey’s drums combine for a rhythmic effect on the record that’s ramshackle yet understated and precise, if that makes any sense. Which it probably doesn’t.

I think to the casual listener Hard Rubbish would probably qualify as a massive bore, or a drag, or any number of things that aren’t true because people sometimes don’t hear with their ears, they hear with their preconceptions. As someone spent on indie rock and who’s a dilettante of folk and country, I nonetheless find myself rapt at the dialogue that Lower Plenty so half-heartedly yet brilliantly initiate with this project. The band members are culled together from harsher, edgier Aussie groups to come together around a kitchen table, to “jam” single takes at an 8-track with just vocals, percussion, and a couple guitars (and sometimes not even all of that) into a record that sounds rich and fulsome through its ambiance and quiet confidence, to put to tape what overcast Sunday afternoons and ever so slightly downcast spirits and the last fifth of gin sound like, perfectly—as if these idioms were really just magnetic signals all along and this, finally, was the band to figure out how to record them. Hard Rubbish reminds me of when I liked Smog records but, unlike Callahan’s lyrical conceits, Lower Plenty never try too hard to draw me in or, conversely, shut me out. They basically just let me sit at the kitchen table, too.

Low fidelity and guy-girl vocals tempt twee descriptors, but here all the cuteness is stripped away without losing an ounce of humor—in fact, the sense of humor is just that much more real and potent for it. And not that you’ll be laughing so much as caught up in a chuckling empathy for something you don’t even understand, which is essentially what is described by a lyric on the opener. It’s as if you are listening to strangers talk about their inner and outer lives in a way that’s both matter-of-fact and oblique, a continuance of a conversation filled with specifics and references that give you absolutely no in…and it doesn’t matter. The words are literate, off-handed, and, in a way, priceless for their blatant disregard for the listener as audience. Because in this unwillingness to explain Lower Plenty achieve an utter lack of condescension. When sentiments are expressed, such as in the titular lyric of “How Low Can a Punk Get,” they feel simultaneously universal and obtuse. I mean, I both do and don’t know what these guys are talking about when they say they’re dancing with a “Strange Beast.” As the record drifts further into abstraction on “White Walls” and then the Low-esque closer, “Close Enough,” it hits not like a growth in pretense but like the hollow clunk of the bottom of the empty gin bottle smacking the table, the band now mumbling about something you really don’t understand…but feel more than ever. It is the record’s emotional core and it is—appropriately, powerfully—inscrutable.

Sometimes it takes a record like this to remind you that pathos can be mundane, bleak, and funny and that artistry can rightfully be a careless craft when it has the balls to believe in its intuitions. Hard Rubbish is warmly prim in its aesthetic and expressive reserve while within that restraint it streams like jazz, both accomplished and impulsive. If it cuts with a dull blade it knows exactly how, for it is no less the incisive for it. The point I’m trying to get across is this: simple, charming, indirect—these are all symptoms of the essential musicality of Hard Rubbish, as if “real music” were actually a thing that could be separated from the imitations, and then few better examples would there be than that of this record compared to all the lazy, amateurish lo-fi folk pretenders that could claim to be contemporaries and categorical cousins. So, to the un-jaded, yes, boring, but to these well-worn ears, Lower Plenty drop some serious knowledge.