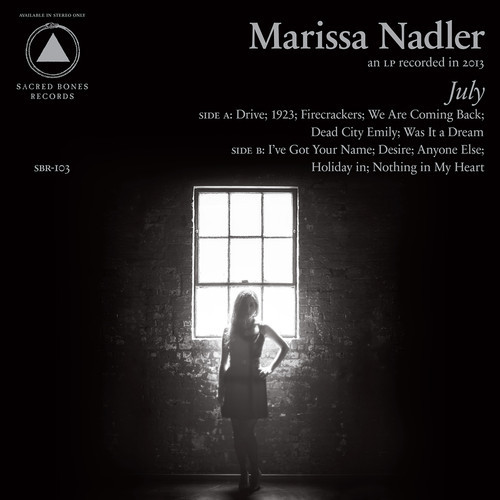

Marissa Nadler

July

(Bella Union / Sacred Bones; 2014)

By Corey Beasley | 14 March 2014

In the permafrost clutch of a relentless winter, it can be easy to forget how oppressive the heat of the summer can be. Marissa Nadler calls this album July, but you’d be forgiven for wrapping it around you like a cloak in January, abandoning the struggle to keep warm and diving headlong into the cold. At least you’d be making the choice. Nadler populates July with characters who understand that sort of small victory—they’re worn down, deeply wounded, but at least they know enough of themselves to lean into the darkness instead of cowering at it.

Over the past decade, Nadler has proved expert at making music that works like mist: their spare arrangements come on with an immediate, quiet beauty, but their gentle weightlessness belies how quickly they can envelop you, as well as the bewitched, eerie sense they leave behind as they retreat. July has Nadler making two subtle but effective tweaks of this style. Here, she worked with producer Randall Dunn, whose experience on projects ranging from drone metal (Sunn O)))) to psych-folk (Akron/Family) makes him a perfect choice to suffuse Nadler’s songs with a touch more heft and a palpable dread that runs through the record like a slick of oil on a cool, clear stream. Nadler also boils away some of the layers of metaphor that had come to mark her densely-woven and evocative lyrics, writing instead with what remains, a more direct and confessional style that can often be sharply bracing. When she sings, “If you ain’t made it now / You’re never gonna make it” on opener “Drive,” it properly stings—she’s tapping into the alchemy at the heart of decades of folk music, the way that second-person pronoun makes a line full of ambiguity and generality feel as personal as a slap to the mouth. But Nadler reveals those lines to be snippets from a character’s inner monologue, zooming out in the next lines to show a singer onstage and the image that provoked the character’s initial burst of despair: “Seventeen people / In the dark tonight / You see some familiar faces / Behind the cellular lights.” This talent, the way Nadler blends the universal with the intimately heartbreaking in the space of a few breaths, makes July in its best moments as vivid as a film, its characters projected to life right in front of you.

But the additional swath of color Nadler and Dunn daub onto these songs allows, when compared to much of her past work, the music itself to carry almost as much of July’s emotional payload as Nadler’s lyrics do. The record’s centerpiece, “Was It a Dream,” showcases that compositional strength, as Nadler’s relatively vague lyrics pick up extra force by passing through bright walls of reverb-laden electric guitar and Eyvind King’s economical string arrangements. On the other hand, a track like “I’ve Got Your Name” lets Nadler’s words float to the forefront, carried aloft by her remarkably beautiful voice, as a simple keyboard melody knows enough to set the tone and get out of the way. “Changed in a rest stop into my dress,” she sings in a dead-eyed quaver Lana Del Ray would give millions for, “Be sure not to touch the floor / I’ve done that kind of thing before.” The song, like all of July’s high points, isn’t a showstopper because it crescendos to an obvious climax—it’s a showstopper because it doesn’t, letting the listener instead soak in the tension of Nadler’s chanted coda, “I saw fire then,” until you realized you’ve been holding your breath for almost three minutes.

If there’s a fault to be found in July, it’s the record’s tendency toward monochrome. The album, at a distance or on a first handful of spins, seems to blur into a single song cycle. The tempo remains steady, Nadler’s immaculate voice hypnotizes with its swung-pendulum power, and the subtle sprinkling of additional instrumentation can be light enough to breeze by on a first or second pass . But let July breathe with you for a time, and its rhythms—the small shifts in mood, the way Nadler sprinkles barbs throughout the album to play off of more ruminative lyrical material like tripwires springing a trap in the instant you realize where you’ve stepped—become distinct. This is a break-up album, a cohesive work embodying a singular mood, and Nadler, like any great artist, sets the scene with such careful, immersive depth that it can be difficult to the seams in her work until you explore every inch. “July 4th of last year,” she sings on “Firecrackers,” “We spilled all the blood: / How’d you spend your summer days?” Later, on “Was It a Dream,” she admits, “It’s true I lost a year stumbling from room to room / Hoping I’d wake up somehow next to you.” That sense of lost time, of the way losing someone can make them seem at once irrevocable and, in the way the pain of it nags and scrapes at you long after they’ve disappeared, never quite gone enough. That’s the spirit of July: a forever attempt to put your hand around something that’s not completely there. It can be a difficult album to hold, but it gets its arms around you.