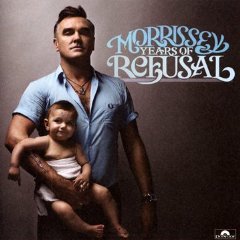

Morrissey

Years of Refusal

(Polydor; 2009)

By Logan Young | 17 March 2009

Diva, animal lover, inexplicable Mexican hero, hirsute bane of both lawyers and record labels alike: as a person, at least, Morrissey is indeed a lot of different things. After all, the reigning master of mope has had almost half a century to fashion himself into exactly the kind of man he wants himself to be. Less dynamic is Morrissey the artist, and for anyone following his brood from Manchester to Rome to present-day Los Angeles, the song remains the same. Formulaic almost to a fault, here’s the thematic template, unweathered and unchanged since 1982, for nearly every Moz song: the promise of romance, the onset of paranoia, pangs of fatigue, love’s impracticality—the ultimate resignation of it all. Heartwarming and uplifting stuff, for sure.

Honestly, it’s probably what’s kept him relevant all these years. Depression has always done the body good, financially anyways, and it’s not like Morrissey was the first to peddle pain for profit. Finding his own creative voice during the “heights” of Thatcherism, it’s only fitting then that his best, most vital sounding record since 1994’s Vauxhall and I comes at a time when America herself is in the shitter: “There is no love in modern life,” he admonishes on the blistering album opener “Something Is Squeezing My Skull.” Not even the psychotropic comforts of modernity (“diazepam [valium], temazepam, lithium”) can help him. “Don’t gimme anymore, you swore you would not gimme anymore,” he pleads.

Tracked live in the studio with swathes of smart pop flair courtesy of 2004’s You Are the Quarry svengali, the late Jerry Finn, sometimes the title says it all: “Black Cloud,” “One Day Goodbye Will Be Farewell,” and, guh, “Sorry Doesn’t Help.” Thankfully, other tunes are a bit more oblique. For the mariachi number “When Last I Spoke To Carol,” Morrissey sounds comfortably numb to the death of a younger suitor; “She had faded to something I always knew,” his detachment bemoans. And on the similarly Spanish-tinged “You Were Good In Your Time”—a mournful portrait of an erstwhile star put out to pasture—he’s deftly aware of the irony.

Written alongside songwriting stalwart Alain Whyte, the album’s apex is also its most contemporary sounding tune. “It’s Not Your Birthday Anymore” is the song Morrissey’s been trying to pull off (in vain thus far) since his twenty-first century renaissance. Callous, violent, and epic beyond reproach, he vacillates only between hushed croon and a soaring, scorching indictment. “It’s not your birthday anymore, there’s no need to be kind to you,” he reasons aloud. It’s as if the pleasures of the flesh he sang about last time on Ringleader of the Tormentors (2006) have finally helped him turn the corner. “Did you really think we meant all of those syrupy, sentimental things we said?” That the track itself is all post-production syrup and sentimental sheen hardly lessens the blow.

Years of Refusal isn’t exactly the phrase best suited for describing more than half a life spent dancing, steadfast, with the tropes that brought Morrissey to his present viability. Severe immutability, chronic fixity or perhaps something more clinically cataract is a better term. For Stephen Patrick Morrissey, it’s not about the taxonomy of change; pain, and his inability to do a damn thing about it, is simply his unfortunate raison d’etre. “I know by now you think I should have straightened myself out,” he readily admits on the first verse of the first track. To this sentiment, what is his retort? “Thank you, drop dead.” And in the end, we needn’t concern ourselves too much with the machinations of some emotionally arrested Peter Pan of pop. Moz will always have the last word, anyways, which makes the barb from the album’s closer all the more appropriate: “This might make you throw up in your bed, I’m OK by myself!”