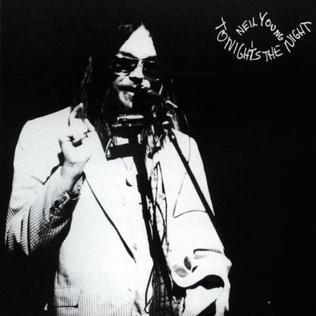

Neil Young

Tonight's the Night

(Reprise; 1974)

By Christopher Alexander | 16 February 2005

“You could strike sparks anywhere. There was a fantastic universal sense that whatever we were doing was right, that we were winning. […] we had all the momentum; we were riding the crest of a high and beautiful wave. So now, less than five years later, you can go up on a steep hill in Las Vegas and look West, and with the right kind of eyes you can almost see the high-water mark – that place where the wave finally broke and rolled back.”—Hunter S. Thompson, Fear and Loathing in Las Vegas

“I don’t think I’ll be going back to Woodstock […] I’m a million miles away from that helicopter day.”—Neil Young, “Roll Another Number (for the Road)”

John Lennon famously proclaimed the dream to be over in “God,” his penultimate song on 1970’s Plastic Ono Band. Certainly he meant it as a reference to The Beatle’s implosion, and many have been content to leave it at that. Seeing as how such a bold declaration comes after the abjuration of many revered figures – several key to the flower-power ideal, such as mantra, Gita, Kennedy, and Zimmerman—Lennon clearly had bigger things on his mind. When the author of “Revolution” and “Power to the People” spoke of “the dream” he meant the capital-D Dream. The Dream that youth would take over the world, that justice and compassion would take root, that cynical, unaccountable and warmongering governments would be toppled by sheer good will. The Dream that collapsed under its own weight, deferred and sagging like a heavy load over the entirety of the seventies.

Neil Young takes a few of his cues from Lennon on Tonight’s the Night. Both records are ragged and loose; both backing bands sound like they’re learning the songs for the first time. They’re both essentially cathartic performances, the primacy placed on conviction rather than perfection. Most of the albums are about people the writers know well. Where they diverge are its subjects: for all its audacity, Plastic Ono Band is primarily an insular affair, dealing mostly with Lennon’s fame and how much he hates it. While just as autobiographical, Tonight’s the Night is, put simply, a record about death.

Ostensibly, it is about the death of two of Young’s close associates – erstwhile Crazy Horse guitarist Danny Whitten and CSNY roadie Bruce Berry. Their deaths had much larger significance in 1973, though: punk had just begun teething at this point, and Young was unsettled by the casual nihilism of Lou Reed and David Bowie. The dark clouds had rolled in, and Young knew it. Whitten and Berry weren’t just any sad drug casualties, but, in his mind, the latest in a lineage that included Hendrix, Joplin and Morrison.

The album is humanized by Young’s dualistic performance: he gets blind drunk to perform songs deeply suspicious of the prevailing drug culture. It’s to his credit that his commentary is never hampered by this. Indeed, no longer encumbered by sobriety, he holds nothing back. “Though my feet aren’t on the ground / I’ve been standing on the sound / Of some open hearted people going down,” he sighs on “Roll Another Number (for the Road).” He can’t even bring himself to sing the unembellished story of a drug murder in “Tired Eyes;” the half that isn’t sung is creaked instead, but the emotional resonance is always pitch-perfect. Placed at the end of the record, it comes off as a desperate plea, a quixotic cry to wake up from the nightmare of 1973.

Neil’s vocals on Tonight’s the Night deserves its own review (as does each and every track; Jimmy McDonough rightly asserted that an entire book can be devoted to the dread-laden piano warm-up that opens “Tonight’s the Night”). It is literally the sound of someone losing their innocence. Compare his hoarse bark on “Tonight’s the Night” to anything on Harvest (or, for that matter, anything from the Homegrown sessions that were scrapped in turn for the sudden release of Night). Take, even, the shaky “Borrowed Tune,” a holdover from Time Fades Away but wisely included here. Here, we find him isolated with his piano and harmonica, watching the world from his room and copping melodies from the Rolling Stones since he’s “too wasted to write my own.” It’s as devastating a vocal performance you can find, even in Young’s formidable canon, and it sounds positively genteel in the face of the rest of the album. His trademark sweetness is gone, replaced by an ineffable but palpable dread. It’s nasty, caustic, and jagged. Aged 27, Neil Young had become a bitter old man, and didn’t give a fuck.

Not about fame, at least. “It’s just a game you see me play,” he shrugs in the harsh “World on a String;” it “doesn’t mean a thing.” “I’ve been down the road, but I’ll come back / Lonesome whistle on the railroad track / Ain’t got nothing on the feelings that I had,” falling a few notes south of the high note in “Mellow My Mind.” He sounds perpetually haunted by ghosts throughout the record; so when a ghost really does show up on record it’s almost unsurprising. Danny Whitten co-wrote and sung “Come on Baby Let’s Go Downtown,” an almost comically frivolous old song. Placed squarely in the middle of Tonight’s the Night, though, it is at once a commentary on a feeling lost and a way to place the album’s raw emotions in more subtle relief.

Like John Lennon, Neil Young had the honesty and the artistic wherewithal to hold nothing back, to be “wide open to his pain,” as some would say. Like Dr. Thompson, Neil Young had the right kind of eyes to see the high water mark. Tonight’s the Night is a title that suggests an attempted recapture of the sixties halcyon: “sparks can go in any direction, the time is now.” It also suggests a harrowing finality, and in its drunken mourning, a sober recognition of the end. The wave was never rolling back, and the hippie dream was forced into its day of reckoning. It’s all coming down. Tonight’s the night, yes it is.