Patrick Wolf

The Bachelor

(Bloody Chamber/NYLON; 2009)

By Conrad Amenta | 17 June 2009

The Western world of 2007 seemed determined to wile away at its post-apocalyptic mores. It shuddered under a defining cultural agitation, dark, unthinkable complexity, nebulous morality, and inescapable doom in the form of unending war and global warming and pandemic disease and the looming precipice of the Western decline. It was a year that seemed to culminate in the previously unthinkable event of the aesthetically and morally terrifying No Country for Old Men and There Will Be Blood winning both universal acclaim and Oscars, as if we were all in on the same sick joke. Mainstream cinema and music alike caught up to the festering subtext of anxiety, paranoia, and apocalyptic change. Artists seemed to paint almost exclusively in shades of grey as a result. I think that, years from now, 2007 may come to represent a reckoning of sorts, the year Western artists decided to hold up a mirror, not to the brilliance of their countries’ past achievements, but to their darkest, totalitarian, hegemonic fantasies and the tragic, inevitable, unsustainable nature of it all.

It was into this fascinating and vital year, one which may come to define at least the first few decades of 21st Century moral thought, that Patrick Wolf, once thought to be among the early century’s most vigorous and unapologetically romantic songwriters, bore the insipid and utterly disposable The Magic Position. An artist that seemed to embody all of the qualities necessary to drop a resonant, cultural bombshell, that seemed, with The Wind in the Wires (2005) to presage 2007’s complex ambitions and insecurities, was thoroughly self-neutered, relegating himself to explorations of ego and pap. The album seems much more appropriate for the easy self-congratulation of these early years under the messianic Obama. So, it was with some pleasant surprise that I concluded, on first listen, that The Bachelor sounds like what I thought The Magic Position should have been. That surprise, as that score up there gives away, turned out to be fleeting.

Here Wolf is darker, visceral, aggressive, at least acknowledges “hard times,” even if then quickly dismissing them with “we’ll work harder,” and the record is characteristically bombastic in a way that is clumsy and staggeringly overproduced but also displays the range of Wolf’s abilities and skill, especially when he brings that cornerstone of a violin into the mix. But the album is one long red herring, informed and diluted by the consistent distraction of overstylized fluff. “Count of Casualty” seems like a caustic tributary, and “Who Will?” seems like it marches alongside the gladiatorial balladry of U2, and the album seems to have groped around long enough to have found its testicles. But that’s just it: Wolf has become the primary subscriber to the mythology of Wolf as exciting and burgeoning writer. He dispenses words like “revolution” like so much Halloween candy, thus emptying them of any meaning or value; he hits all the pleasure points of important songwriting, thus allowing critics and fans alike to hit their quotas for appearing vicariously politically and culturally engaged, all without saying a single thing worth remembering. Confusing, considering The Bachelor was apparently conceived as an overtly political effort. I wonder what that would have looked like, because it’s apparent that Wolf instead opted for ego writ large; Depeche Mode with less of David Gahan’s complicated, thoughtful self-inspection; a zeppelin’s worth of hot air and writing that sounds prettily and moodily like it has something important to say without ever getting more specific than that.

I can’t help but wonder, when Wolf sings “I don’t fear oblivion,” if it’s one, or some of, or simultaneously the following: that he’s overused words like “oblivion” into meaninglessness; that the sustained critical blowjob he’s enjoyed since Lycanthropy (2004) has imbued him with a sense of indestructibility that makes statements of vulnerability impossible; or that all of these character masks and costumes and performances are unconscious attempts to put distance between Wolf and his insecurities, the indisputable fact of his mortality or whatever. The canny and predictable effect also being that there’s some distance between Wolf and his audience, too. A song like “Damaris” is so paradoxical, so confusing, precisely because it’s fundamentally a gorgeous song that’s then blown into regions so far from accessibility by its series of indisputably bad decisions, the worst but only one of which is the song’s (and the album’s) excessive use of a passionately chanting choir. And speaking of that random trend and I-pray-soon-over piece of kitsch, The Bachelor reminds me the most of the intolerable Passion Pit. They both employ a kitchen sink approach to songwriting that, at its best, reflects a hyperglossic generation of shoppers and social networkers and, at its worst, incoherent and uncontrolled self-indulgence. The only way the inclusion of a song like “Battle,” with all of its horrible vamping and electric guitar and “fight!” chants, can possibly be forgiven is with a well-nourished sense of irony—Patrick Wolf seems like one of the least ironic people in the entire world.

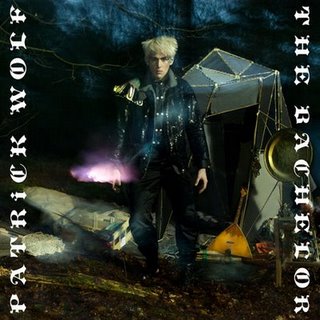

As one might guess from the cover image, in which Wolf emerges The Man Who Fell to Earth-like from some kind of prismatic tent with a scattering of lutes and ancient bard implements on the ground, the songwriter imagines himself as either the passive conduit of a grander narrative or counts himself among chameleonic artists like Bowie or Gabriel or Bjork who refract their music as much through the performativity of image as through what is actually spoken. Those writers, too, have been guilty at one point or another of deriving their music of their image as opposed to vice-versa. But Wolf is driving what still sounds like a visionary take on songwriting farther and farther from his true breakthroughs on Wires, relying on what is as much a satirical characterization of Patrick Wolf as an actual Patrick Wolf album. The best of The Bachelor—the title track, “Casualty,” “Who Will?,” the saccharine textures of “The Sun Is Often Out,” some nice percussion—is mitigated by an almost Corgan-esque inability to self-edit. And, like Corgan, Wolf seems increasingly exiled to the island of his own mythologies, imposed in part by critics casting about for farsighted, creative writing and in part by a narrative thread he’s, however knowingly, veined throughout this bloated aesthetic.

Patrick Wolf still engenders a puzzling and sometimes fascinating discussion about romanticism and pretension and authenticity and songwriter worship, but what’s disappointing is that he seems to no longer be a part of that discussion, simply the subject of it—so much so that even his own music seems to be about whether or not he’s for real. His bravest gestures seem to be wardrobe related, stoking and inflating the listener’s gradual epiphany that to be a fan of Wolf is to reinforce the difference between Wolf and his audience, the singular, self-legitimizing artistry of the artist and passivity of the audience. In the universe of his albums, Wolf is the alpha and omega, Apollo and Dionysus. Ultimately, the mirror he holds up is not to the world, be it that of 2007 or 2009, but to his own face.