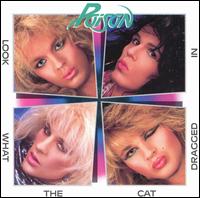

Poison

Look What the Cat Dragged In

(EMI; 1986)

By Scott Reid | 1 September 2005

I’d love to see someone in 2005 give Poison’s Look What the Cat Dragged In an honest, non-ironic, non-hateful review.

Actually, I didn’t pick this album because I have any attachment to it or anything. The first idea that popped into my head was Lou Reed’s Mistrial… but Reed is too obvious a choice for a site such as yours. About two seconds later, Poison screeched in front of Reed from whatever dark corridor my mind had buried them in. Throw the people a curveball, I say!

Thx, Paul

Non-ironic review of a Poison record? Not a problem. I mean, an ironic take on a terrible band is to embrace them, right? Rest assured, this review will be non-ironic.

But non-hateful?

Sorry. No curveball.

First, this review has little to do with the hair, the makeup, the overwhelming reliance on both the MTV just-look-good era and Motley Crue’s success, the co-opting of every superficial aspect of sugary ’80s rock only to do absolutely nothing with it, or the dumbfounding choice to get chicks by—naturally!—trying their best to look like them. Which opens up a whole ‘nother bag of issues that’d surely be far more interesting than their music, but that’s not the request, so….

My real problem with this band, and this album by extension, has something, but not all, to do with how terribly bland and substanceless their music is, even if it was never meant for “polite art gallery listening” or anything besides good times between guys sharing the band’s ingenious quest to use someone else’s music to get laid. It plays a factor, of course; a shitty song is a shitty song is a shitty song. But this…this mostly has to do with C.C. Deville.

Well, kind of. If you’re too young to even remember good ‘ol C.C., think of a really zany (what a shitty word; thanks Shakespeare!) Bill from Bill and Ted mixed with a little Chris Katan and a lot of wigs, hooked badly on coke and really eager to impress. It’s an unintentional schtick—it’s why, like frontman Brett Michaels, he’s memorable despite being in such an unremarkable band, and why a site like this would pronounce him “the greatest Rock and Roll Axe man of all time.” Despite, you know, that being a ridiculous thing to say.

But he’s a “performer,” a personality, exactly the kind of guy who would be in a band that could—and did—only flourish in the ’80s. But even in ’86 this must’ve sounded vapid. Even if you give this band every benefit of the doubt, even if you don’t have an irrational hatred for C.C. Deville, and even if you just don’t care about lyrics like “whole lotta lovin’ satisfaction guaranteed,” it’s still hard to not come out the other side of an album like Look What the Cat Dragged In thinking that this is some awfully pointless music.

And it is.

Ok, so maybe that’s harsh. You ask for a non-hateful review and I unearth some secret rage toward C.C..

I can’t be honest and positive about this album at the same time, it’s just not possible. But how about this: I’ll make a sincere attempt at being balanced, starting…now.

Maybe it’s because I grew up with Nirvana and the other Seattle crop of anti-hair metalists. Maybe I just care specifically about certain aspects of music that Poison are oblivious to. Maybe, and I heard this a lot with the Darkness, "I just don’t know how to have fun." I mean, it is possible that Poison aren’t nearly as bad as I think, right? Hell, maybe C.C. Deville isn’t stupid, either. He did OK on Celebrity Rock N’ Roll Jeopardy that one time, though I’m not entirely sure he realized it. The band did get worse when he was kicked out. Comparatively.

Besides, this is one of the big rock band of the ’80s. For a pointless band, they did well; they have a massively popular monster ballad (“Every Rose Has Its Thorn,” which is not on this record, so maybe that’s a selling point for you, maybe not) that’ll likely keep them a household name, millions of records sold, enough interest to support a (disastrous, to Crue proportions) reunion tour, trainwrecks of solo careers, d-level celebrity, the whole nine.

And, if you want to get really comparative about things, considering the careers lows that would follow, Look What the Cat Dragged In is, without question, the “best” of Poison. It’s good (remember, comparative) hair-n’-makeup pop-metal if you like that kind of thing, good fodder for ironists everywhere, good music for thousands of bad teenage parties, good background noise for people who equate artistic sincerity with a band taking itself too seriously. They helped to fill a goldmine more-entertainment-than-music void in the ’80s music shitscape, one that bludgeoned this trash into the forefront of popular "rock" for many unnecessary years. And when we reach the next pop wasteland that’ll feed us our next "Talk Dirty To Me," albums like this will almost certainly be fondly remembered as a milestone.

Only they’ll be wrong. And I could go into hundreds of reasons why I think Poison are the least worthwhile rock band to ever hit it big, but why bother? How could I possibly explain why one band’s music could bother me so much?

Way back in ’71, Lester Bangs wrote a short story/article titled James Taylor Marked For Death. It’s pages and pages on, primarily, (a) his love of the Troggs; and (b) his hatred for James Taylor’s music, and all music like it, because it, in its own inoffensive and pointless way, is what’s wrong with music ("THE LESSON OF "WILD THING" WAS LOST ON ALL YOU STUPID FUCKERS"). He’s just another nostalgic critic, so of course he’s going to hate everything, but a point’s a point.

He goes on to describe James Taylor as "so relentlessly, involutedly egocentric that you finally actually stop hating the punk and just want to take the poor bastard out and get him a drink, and then kick his ass, preferably off a high cliff into the nearest ocean." Not long after, he reveals a repressed urge to brutally kill the man by stabbing him with a broken-off bottle of the cheapest local wine he can think of. The tone starts to soften after that (somewhat), but his instinctive, stubborn dismissal of Taylor as a disastrously wrong turn for music (and, because he loves good music so much, his own well being) lingers. He calls for sides to be drawn, for separations and distances to be placed between people who listen to "music that’s alive" and people who listen to. . . that. It bothers him that much.

Poison are my James Taylor.