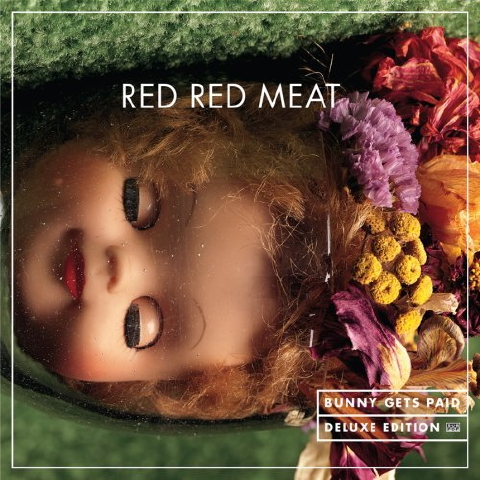

Red Red Meat

Bunny Gets Paid

(Sub Pop; 1995/2009)

By Peter Hepburn | 17 April 2009

Even though it has been out of print for a while now, Bunny Gets Paid is a known substance. A small core of critics and fans has rightfully sung the praises of this record for years, to the point where, even before this reissue, it had taken on a semi-classic status as a potential mid-‘90s Chicago rock staple that slipped by while the Pumpkins and Phair and Urge Overkill and all those others got big. It is better than anything any of those bands ever put out because it’s better than most indie rock in the ‘90s, but in the same way that Califone—the foremost band to emerge from the hull of Red Red Meat—seems to now exist on a plane of their own, RRM were just elsewhere; they weren’t competing with Pavement or Sebadoh or Archers of Loaf or Guided by Voices, just making extraordinarily beautiful, indecipherable rock music. On Bunny they got it very right.

Approaching a record as respected and well-loved as Bunny, one I’ve spent so many years and built so many personal associations with, is tough. Possibly beyond my critical prowess, even. So I figured the best course of action would be to call up a guy who claims not to have listened to the record in years: Tim Rutili, lead singer and songwriter of Red Red Meat and Califone.

I was interested in Rutili’s read on what set Bunny apart from the band’s other records. To my ears, Jimmywine Majestic (1994) has always been where Red Red Meat brought the Stones and the Faces to the grunge era, and Bunny is where the drugs got the better of them, where everything started ripping apart around the edges. By the time they got to 1997’s There’s a Star Above the Manger, they’d found Can and recessed entirely into those edges. For this one album, though, they captured the prettiness and the damage of a very particular moment—for Rutili it was about the recording process and the reaction that the band members had to a constant year of touring in support of Jimmywine. Having really come into their own as musicians out on the road, they decided it was time to move in a more experimental direction: “We wanted to make something that we liked and not something that was necessarily expected.”

Part of this approach involved going into the studio less prepared than they were with the previous albums. Both Rutili and drummer Brian Deck also had new children and the studio schedule was accordingly more flexible than it had ever been. Since they only had five or six songs ready, the rest were written together in the studio, and the record bears the mark of something built together, organically, over time. Even the prepared songs came out looking different in some cases; Rutili wrote “Rosewood, Vox, Waltz + Glitter” prior to recording, but the hugely percussive track on Bunny is a far cry from what he had originally envisioned. “That was the first time we really got to stretch out and experiment in the studio. First time we wrote music in the studio. It’s where we kind of became ourselves, figured out a bit of who we were and wanted to be.”

It’s the second half of the album where this comes through most. All of those songs, except “Oxtail,” which Rutili singled out as being particularly fun to revisit, were written together in the studio and also happen to be the songs that seem to benefit most from the careful remastering that went into this reissue. The woozy, half-lit “Variations on Nadia’s Theme,” the track that gives the album its name, really stands out now: the band is playing underwater, restrained but still inventive (listen to that wobble and creak), and Rutili is just barely mumbling over the swells of noise. The fever-dream “Sad Cadillac” and blues freak-out “Taxidermy Blues in Reverse” draw everything toward the darkest extremes that RRM could manage only to have the band close the album with a rendition of the Rudolph the Red-Nosed Reindeer song “There’s Always Tomorrow.” It’s a weird, ambitious final set, and I don’t think Bunny would be nearly as memorable without it.

I also asked Rutili about the record’s lyrics. On Jimmywine there are plenty of moments of clarity—just think back to “Braindead” and that simple, albeit indecisive, declaration of “I know where to find you / When I want you / But I don’t.” Bunny doesn’t have those. “Gauze” has all the build and splendor of a Talk Talk anthem, but the central refrain of the song is “Mink eyed / Marble eyed / In the gauze / In the weeds.” I don’t have a clue what any of it means and, ‘til I went back and checked, I wasn’t half-sure what most of the lyrics were. “Meaning is overrated,” says Rutili. “It gets in the way of real creativity.” He was writing free verse, pulling himself inward, and the band members just sort of picked up on what it was about; he says he is willing and able to explain songs when needed, but that his band mates almost never ask. I get the impression that they were so clued into one another and working together so closely that the tone and meaning emerged almost spontaneously.

As for how the reissue came together, Rutili made clear that it was done at the request of Sub Pop, and that they’d be happy to do more. They sifted through the old tapes and then sent Deck, best known now for his production work with Modest Mouse and Iron &Wine, to do the remastering work. What comes through is the tone and depth of the album: Brad Wood did a great job with the original production, but hearing “Rosewood, Wax, Voltz + Glitter” as intended—that is, as an absolute lumbering monster of percussion—is breathtaking. Throughout the album, Deck both draws out the mean bite in Rutili’s guitar tone and highlights the sheer percussive power of the group (by 1995, the band was half drummers, both of them phenomenal). The effect is enveloping and gorgeous. Even “Sad Cadillac,” probably my least favorite track on the original, is here recast as a creaking, sludgy, all-swallowing beast, grotesque and enthralling.

The disc of bonus material presents a half hour of alternate versions, covers, and b-sides. All are good, especially the Rutili solo version of “Chain, Chain, Chain” and the rollicking “Saint Anthony’s Jawbone,” but none are really essential and they lack the sort of cohesion that defines Bunny. The package as a whole is worth it, though, even if this is a record you already own and love. I asked Rutili how it was for the band to go back and revisit Bunny, to which he less-than-enthusiastically responded, “Well, we went back and we all still kind of liked it.” It’s strange to find myself more passionate about this record than the guys who made it, but I’ll chalk it up to modesty and argue that “kind of” really doesn’t cut it. This is a phenomenal record, has been since its release in 1995, and it’s to Sub Pop’s credit that they put it back in print. This reissue serves as a reminder of what a substantial leap forward it was for the band and what a beautiful, powerful, and well-structured album it still really is.