Regina Spektor

Far

(Sire; 2009)

By Christopher Alexander | 13 July 2009

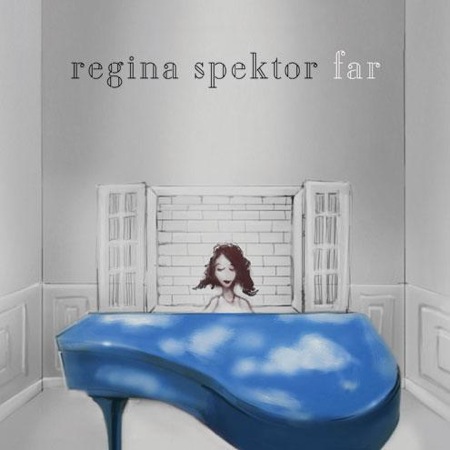

The window of Regina Spektor’s apartment may be walled in, but on the cover of Far her piano is made of clear skies. The image is obviously meant to be an inversion of reality to strike at some beautiful metaphor, but one instead wonders if her real piano is actually made of bricks. I find the image striking for another reason: the record features strong writing augmented and driven by Spektor’s irrepressible quirk, but, like Begin to Hope (2006) before it, is less free, less personable than her best record, Soviet Kitsch (2004). Far features a murderer’s row of big-name production talent—Jeff Lynne, Jacknife Lee, David Kahne, and Mike Elizanado (Dr. Dre’s longtime bassist, who also worked on Fiona Apple’s defanged Extraordinary Machine [2005])—to ostensibly augment the pianist’s vision, but the effect instead is to largely strip the songs of vitality and humanity. The album’s artwork is a perfect visual accompaniment to its album: effortless, natural songs performed by an enigmatic performer and trapped in a chrome, hermetic casing.

This is still a better record than Begin to Hope, on which Spektor had one foot in her anti-folk past, one foot in her handlers’ vision of neo-Lilith Fair, and both hands thrown up in the air in the classic “I dunno” gesture. Far benefits from a basic hegemony the prior album lacked, save for the Elizanado production “Building” (which began life as a David Byrne commission for his Playing the Building installation), featuring expected machine-like percussion, atonality, and fortissimo cello. I’ve no idea how this played in the installation, but lyrically this is Spektor’s laziest writing, the singer playing the role of Kurzweilian automaton and rhapsodizing the joys of being updated/downloaded daily. Elizanado’s two productions at the album’s start are more representative and, for a man of his CV, shockingly sympathetic. Spektor sings of a computer hand-made from dry macaroni on “The Calculation,” and he applies a deft, subtle processing of her cooing to approximate the vocalist’s imitation of an ancient Moog. Even more stunning is the dramatic dynamic changes that moor “Eet,” and she responds with one of her best falsetto performances. Would the same could be said for Jeff Lynne’s productions, each one featuring drum loops or patterns that his engineer probably knocked out on his lunch break.

Spektor remains a great songwriter, although a fundamentally misrepresented one. I have many of the same problems that Conrad does with “Laughing With,” but I disagree that the song is the stereo equivalent of the classic “Hang in there” kitten poster, or a soundtrack for the brainless motto that there are no atheists in foxholes, har har. If anything, it turns the axiom on its head: the “ha ha” Spektor (literally) sings in this song is more spiteful, more cognizant of the indisputable fact that, in the totally improbable event that there is someone at the helm, He’s exceptionally cruel. (“God can be funny … when presented like a magician who does tricks like Houdini / or grants wishes like Jiminy Cricket and Santa Claus / God can be so hilarious.”) That’s why nobody likes Him, which makes the insincere cliche to all ridiculed kids everywhere such a kiss off—they’re not laughing at God, they’re laughing with God, while He wears that stupid striped shirt with wet pants and pulls the wings off of flies besides.

But Conrad gets the general problem with post-DIY Regina Spektor completely right: whereas before Spektor’s humor could get her through fearless personal self-excavations, with observations as startling as they were uncomfortable (or juvenile), she has since scaled back. “Folding Chair,” in spite of the funny line “I’ve got a perfect body / because my eyelashes catch my sweat” isn’t helped by its “Heart and Soul” moon/spoon/june line scheme (or Jeff Lynne’s production autopilot—a solo live version is floating around that puts Spektor’s vocal tics in starker relief, benefiting this pastiche to no end). “Eet” may be her best song, but the lyrics are mostly placeholders about a life lived inside of headphones (the woman who wrote “Summer in the City” can do better than “It’s like forgetting the words to your favorite song / You can’t believe it, you were always singing along”). “Human of the Year,” which has all the portent and production of a major set piece, envisions a ceremony in a cathedral for the titular award. It’s an idea that has a lot of potential, but the best image she can muster is the sound of car horns creating the character’s theme song—an image which, you may have noticed, isn’t all that exciting. And I have no idea what cerebral short-circuit made her think “Dance Anthem of the ’80s” was a good idea, but with an excessively syncopated bass line (doubled by Spektor’s voice) this borders on self-parody, and then crosses over and mates with the local populace.

The album has been used as effective wallpaper for the corporate bookstore where I work; I never notice that it’s on until it stops, much like a refrigerator. I was surprised that it holds up well to close scrutiny—in spite of my reservations, the album is well performed and crafted, with a surprisingly mordant thematic unity touching on mortality and the soured promises of childhood—but I’m still bothered by its anonymity. Even Dar Williams succeeds in at least annoying me at work. I keep thinking that Soviet Kitsch would never fly in this environment—certainly not the meter shifts of the contemptuous but playful “Poor Little Rich Boy,” or even the trill piano that begins the should-be hit “Us.” There was a lot of Regina Spektor in her best work, and while the tics and idiosyncrasies remain, Sire records has spent a lot of money to safely couch them in malls (hence her smiling enigmatically on that Mona Lisa cover). That music remains throbbing at the center is a testament to the Regina Spektor’s talent; that this record can be so antiseptic is proof of the poverty of her acumen.