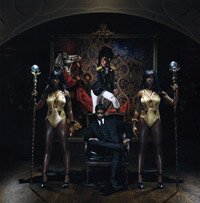

Santigold

Master of My Make-Believe

(Atlantic Records; 2012)

By Conrad Amenta | 30 April 2012

To rely exclusively on what Google burps up about Santigold is to believe that Santi White is operating in a space reserved for the auteur. The Spins and Rolling Stones of the world employ their comfortable hyperbole to describe what is essentially just left of the mainstream’s blinding center. Like M.I.A., to whom White is often compared, there’s just the right amount of cultural and lyrical otherness that we white male music critics like to hold up as evidence of our nuanced taste, and just enough riffing guitars and big polished production numbers to listen to what is recognizable. And so you realize now that, yes, this review may turn out to be another reaction-to-the-reactions review—Master of My Make-Believe is not so bad, but the way most of us are going to write about it is insufferable.

Because there isn’t much that makes Santigold’s music exceptional, and it’s not designed to be. White is comfortably ensconced in sight of the mainstream’s lowered bar. She excels at catchy pop music, much closer to ’80s femme-rock and new wave than the watered down “world” tunes to which critics occasionally allude and play up. (Her music can be reggae, but the way that Ted Leo had that one song that was sort of reggae.) None of these things bar White from credibility, and in fact Master of My Make-Believe is a nicely constructed bit of pop driftwood—enthusiastic, with creative percussive elements and appropriately cynical recurring themes, like “We’re the keepers / While we sleep in America / Our house is burning down.” It’s just that the type of credibility White earns is a lesser badge, and her music changes no aspect of the Teflon surfaces in which she finds her reflection.

Throughout, White affects the posture of the disaffected. It’s tempting to conclude that to be a mainstream songwriter in 21st Century America, with even a passing sense of its pessimism, is to at least make reference to that disaffection. But it’s what’s done with that observation that transcends artists from the hangers on. Master of My Make-Believe, with its many reference to public gatherings and alienation, may be one of mainstream pop’s first to acknowledge the existence of an Occupy Wall Street, but it also reaffirms mainstream pop’s inability to handle that event with a modicum of dexterity.

Judging the album in a vacuum of pop values, it’s an improvement over White’s 2008 self-titled debut, which created and maintained a buzz despite at times sounding like a slightly thornier offshoot of the same power-pop trend that produced Fefe Dobson and Avril Lavigne. “Disparate Youth” is exacting to the point of clockwork, rolling about the dance floor with precise turns and texture, and it’s probably the best thing she’s ever written. Likewise “This Isn’t Our Parade,” “The Riot’s Gone,” and “The Keepers,” which hint at populism and dystopia even if they’re rendered in bulky generalizations, are creatively arranged and beautifully performed.

Lyrically, however, White never pins her work down, and never commits to an actual position on anything. She addresses a nebulous “you,” asking him/her to “come down” and so on. It’s totally unclear if she’s addressing the audience or someone specific, but these rhetorical blips, like the production sheen, are designed to be superficial and inoffensive. She has the curled lip, the pointed finger, and believable outrage, but we still don’t have any idea what she’s talking about. One ends up feeling like the boring “Freak Like Me” and “Look at These Hoes” fall closer to the tree than the album’s supposed spiritual centerpieces.

What White seems like, most of all, is simply a person with access. Her varied collaborations, her long and storied history in the music biz—first as an A&R rep for Epic, then as a co-writer and executive producer, and finally as a full-fledged solo artist opening for Coldplay and Jay-Z—all allow for Master of My Make-Believe to exist as something of a media/brand event. One feels that one is far more likely to encounter it paired with a commercial for lifestyle electronics than the causes to which it seems to pay some minor respect. It’s not the sort of thing one pins their organic, folksy dreams upon, though you get the sense it was born out of that interest and perhaps lost its way over time.