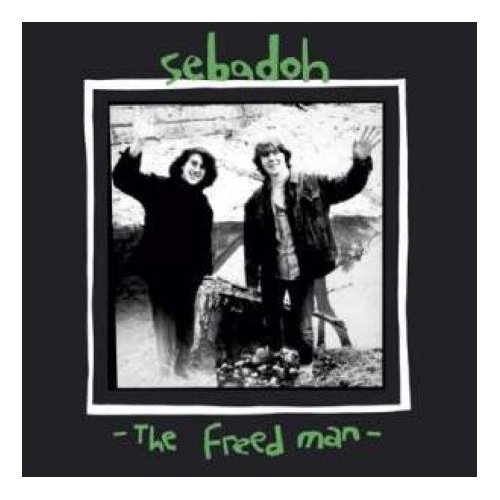

Sebadoh

The Freed Man

(Homestead/Domino; 1989/2007)

By Philip Guppy | 30 November 2007

I bricked up a wall around my cassettes long ago; it wasn’t easy but some things you just have to let go. I started out with them: little annotated documents of discovery mapped out on anonymous brown ribbon, my awkward teenage fug catalogued. Tactile, lovingly scribbled doorways. Sure I took a swing at building a sizeable vinyl collection, that’s what I assumed the serious collector did to blood themselves, trawling car boot sales and flea markets, all giddy when I unearthed that Orange Juice album with the dolphins on the cover from a raft of China Crisis and T’Pau albums (for only seventy five pence!). Vinyl was beautiful and mythical, it existed as an object to be fetishised like a tablet from the mount, but cassettes were my medium. I owned their content, they let me in on the process, gave me the control to select and sequence in a way that vinyl could never do. I received my musical schooling on cassettes.

I can still remember the all-enveloping thrill I got from putting together a C90, two instructional sides that sucked up all of my attention; had to flow, had to be right. Start out with some Triffids, throw some Jane’s Addiction on there, glue it all together with Tom Waits and Elvis Costello; the choices were loaded with such self-conscious importance, imagining how that girl in class would react, the conversation you’d revel in when she’d brim and say “And I loved that one!” Tapes are artifacts, they are who I was, all my faux-caustic attitude and awkward adolescent smegma; the things I stood for, who and what was worth a damn and why. Time pulled and warped them, they aged and became unique, petrified, mortifying, until I really couldn’t recognise who I was when I made them; did I ever really like “Rhinoceros” that much? Really? The Freed Man exists as the squeezed pulp of mix tape culture, its lines drawn by fingers on pause buttons, boozy with hormonal urges and the need to take things further than simple sequencing. Other people’s songs were great, but to really nail that perfect mix you just have to make the music yourself.

I’d like to claim that I was right there when The Freed Man was released, that I got the cassette with its slashing, porno scrawl cover and drove it around town, grinding sticky gears with ketchup and cigarettes to the sound of snoring cats and after hours hiss. I didn’t. I found Sebadoh later: I’d look sour at my speakers whenever Gaffney’s skronk obliterated the fading taillights of “Two Years, Two Days” with another of his serrated goofs. Loved Barlow and Loewenstein, learned to like Gaffney later; I suspect it would’ve been the opposite way around had I come to them earlier. I probably missed out not having that lo-fi breeding at an early age. With hindsight I can see how that early brick-dust fidelity and the cruelly short attention span involved would probably have suited my teenage self. I was a Salinger kid after all, the usual alienated zit-frosted fumble-wiped down with noise and bad hair; my friends would’ve hated Sebadoh for a start so they would’ve been mine to covet and coddle. They should have existed in my world.

The dead pop and blustery whoosh of the tape stopping and then starting is the defining sound on The Freed Man; it’s the sound that tells you the circumstances that moulded these songs, their flashpoint of inspiration. Every inch of this recording was born wounded, bleeding ambient sound and bad jokes; it’s a punctured balloon, a rotting rag left to stink on a counter. The fret buzz and airy harmonies of “Jealous Evil” are diced with a constant undercurrent of boombox interference, a low voice suddenly obscuring the show like a huge face appearing from underneath a CCTV camera. Nothing can be left to simply be itself; there’s always a freak acoustic storm or screaming voice waiting to piss in the punch but if it was shorn of these fevers the album would be nothing but a sketchbook filled with scraps and pointers. They’re its living environment, the constant interruption of the outside world, its raging id tearing at the corners. Filtered through a thousand pop cultural fragments, The Freed Man‘s contents are a blizzard of half-formed ideas and adolescent fripperies. Set adrift on this bleary extremity are the core values of Barlow and Gaffney’s future symbiotic relationship, that jarring blend of exposed emotions and cross eyed ranting in fetal form, opposite but complementary fragments, one offsetting the other in the same way that a destructive episode will futilely attempt to obliterate pain.

There’s a cohesion involved in this collection, akin to some kind of never-ending road trip, but it’s uneasy and indistinct. Is it the frantic sexual juvenilia that runs through “Soulmate” and “Dance” that draws it together? Is it in the love of classic pop that lurks underneath? The Beatlesy refrain that brands “Julienne” is a sly pointer towards a shared passion for melody that can’t be obscured by any number of croaking Melvinsesque dirges and searches for “solid brown.” Its obviously there in the roadrash production, but that’s too obvious, no, there’s wire and string that wrap these songs and they’re made from societal detritus, the cultural drool that washes around us all. Bad television, intrusive advertising, background noise, all of the interference that we tune out like the hum of a fluorescent strip is thrust to the forefront, a hand in your face. NOT TOUCHING! NOT TOUCHING! CAN’T GET MAD!

Barlow’s talent has always been his unflinching ability to land the minutiae of relationship fallout, simple and economical as a razor slice. He was still developing his gift on The Freed Man: it’s tentative, cloaked in a childlike reticence. There isn’t the confidence apparent to present or even craft something as raw as “Think (Let Tomorrow Bee)” or “Love Is Stronger,” but that gives him the freedom to be more relaxed and playful than he would be on future recordings, getting punched in the nose, even MC styling around a sonar ping on ‘Lou Rap’ with cringing results. Gaffney, however, is in his element, waxing retarded about ladybugs and parasitic family members. Arguably Gaffney’s most fitting record, the mixture of slack-arsed, detuned rambling and sonic garbage suits his aesthetic to a tee. Never content to stick with one bug-eyed idea when twenty will do, he’s given free reign to keel and roll, upending excited melodies with his nauseous, stumbling lips. He keeps the sonic freakouts to a minimum, preferring to rent his psychosis to quieter tenants in this term, but it’s clear that that lurching, scrambled synapse propulsion was spilling garbled seeds, even at this early stage.

This really is a record you deserve to have thrust upon you in your youth, whether you want it or not. It has every right to sound busted and goofy, tender and lost; dusty tape box vomit dumped unceremoniously in a gassy place. All that Saturday morning TV gunk and advertising jingle mince that clogs up your memory, all those pinned and hidden mawkish feelings that you never told on, your thrashing pubescent child; all of it lives on in its hulking sprawl. The Freed Man‘s sonic wash isn’t designed to be broken up into individual tracks; there’s too much spit and sinew gluing everything, unwieldy tumour that it is. What’s really telling is that there are extra tracks included on this reissue and there doesn’t seem to be any clues as to where the real album order deviates and the additional tracks muscle in. Everything is sweat stains and bone growth. The root of The Freed Man‘s appeal, is that it unapologetically renders that universal teenage miasma large in all its confused, messy splatter. Like this review, it sloppily chases its own tail in search of an answer when there isn’t really one to find, the topic at hand too large, too compartmental to ever grasp conclusively.