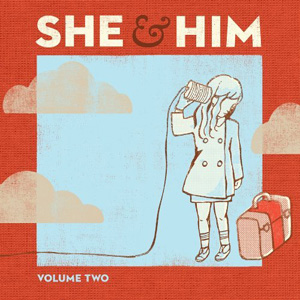

She and Him

Volume Two

(Merge; 2010)

By Sam Donsky | 20 April 2010

I don’t have enough synonyms for “ironic” in my vocab-holster to attempt a full thesis on why Zooey Deschanel’s critical ascent off the pop-singer ground floor has thus far eclipsed Scarlett Johansson’s, but I’ll point out for the record that the quality of their output has been roughly the same. Scarlett debuted with a Tom Waits covers record, which flat-lined with a vengeance and invoked protective language about anti-ethics and Benicio Del Toro. She then followed with a Pete Yorn duets LP, a rather competent Parisian nostalgia rip-off. Now she’s the seventh lead in Iron Man 2. Apologies if that was super-morbid!

Deschanel collaborated with the I-guess-cred-bearing M. Ward to form She & Him, and their debut, Volume One (2008), summoned a shocking surplus of favor for a record with three good songs. And when I say shocking I don’t mean it: on the level of mere product, Volume One‘s deadpan vintage could not have felt less like those Scarlett records. While a cynical ear might have sensed out ScarJo’s M.O. as an urge for indie bona fides (“I like…Tom Waits?”), Volume One seemed to showcase Deschanel’s genuine wish to suppress those same urges, and to keep her iPod to herself.

The pair’s follow-up, Volume Two, feels equally immersed in this wish. Every one of its elements borrows from the same throwback formula, and feels like an extension of a singular, almost anthropological context. Which is not quite to call its context narrow. The record skips around through a variety of touchstones, most from the ‘60s and ‘70s and all indistinguishable from those pursued by their predecessor. AM pop, Cali soft-rock, and straightforward country each take up a healthy slice of She & Him’s aesthetic resolve.

And yet for as much variance as it ostensibly allows, Volume Two feels burdened by a different type of repetition. It is as though its thirteen songs, unable to agree on precisely the time or place, instead converged upon their lone common thread: a shared resistance to pop’s present-day notions. This convergence seems to sum up the band’s idea of timelessness to a T—earnest-as-fuck classicism with a vacuum-lock seal. The vacuum part is crucial; as a record that could pause for plenty of winks, Volume Two manages hardly to do so at all.

I’ll let you decide for yourself whether this is cause for acclaim. Personally, I prefer the winks. They are my hints that I’m engaging with something that’s real. Which I suppose is part of the problem: Volume Two isn’t real. Pleasant or not, its context never escapes past the pose of contrivance. It’s never not shtick—and that’s fine. But even in a world of one pastiche or another, one must ask: what is the difference between this and, say, that desperate “Hov’s still a gangster!” record? Or, at the risk of true belligerence, Hannah Montana? If one is honestly going to take She & Him at face value, isn’t “pastiche” even a bit generous? This is how I am reminded of how bat-shit crazy Beyoncé is: I accept Sasha Fierce because I assume she’s schizophrenic. She probably isn’t, but the point is that those are the stakes: the lower bound here is not “a ‘blah’ record”; it is dishonest art.

Such, in a way, is the paradox of pop music, of what fifteen years ago we might have called radio: that pop is itself a time signifier. Good songwriting may be good songwriting, but it’s almost never timeless in the market sense. It is ultimately but an expression of one or two things: music and lyrics. There is so much else, of course. And from where one culls this else (crudely speaking, from the past or present) necessitates the sliding scale that then becomes criticism. In this way Volume Two feels almost perversely thrill-proof, an exercise on the margins of the pre-consumed. It might sound fresh to a certain set of listeners (insert Urban Outfitters joke), and such cycle-for-fashion might even be its avowed goal. But let us consider this phenomenon on par with re-gifting: as an aggregate it remains cloaked in second-hand news.

And that, finally, is Volume Two’s apex of insincere. Of course it knows that it’s, excuse my language, an indie record. It is exclusively as such that the thing works (exists?) at all. Which is why Deschanel’s Queen Twee repute is a point of such relevance. Not only is it demonstrably true, but it endures here as her record’s very persona. Volume Two‘s is not the definition of indie that means something-for-short. It is the version that signifies quirky on purpose, manic for fun, above the self-constructed fray. If I sound defensive then that’s part of the point: Volume Two is a record, of occasional charm, that comes off all-too-aware of how cranky a response to it other than “charming” will seem. Perhaps its most efficient qualifier is not thrill- but critic-proof.

Which is the long way of writing: Dear Zooey Deschanel’s Shtick, Yes of course I’ll marry you. I am always joking when I say this; she is always joking when she asks. One might call that innocent, or preservative, but I prefer creepy. Volume Two is a harmless record but a finally repellent one. It is the sound of a band breathing through the mouth of a wax sculpture: waving its hands, thumping its heart, whispering some vague something-something about the beat going on.