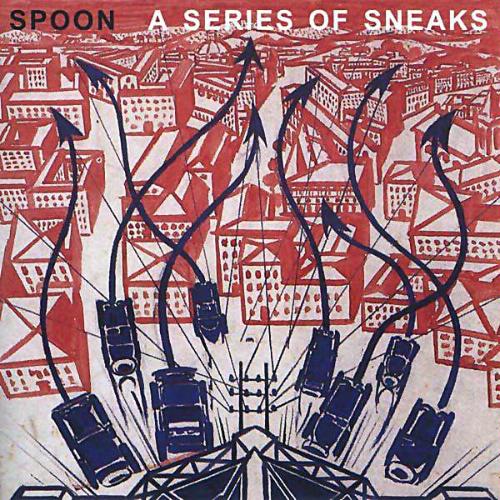

Spoon

A Series of Sneaks

(Elektra; 1998)

By Mark Abraham | 16 March 2006

In 1998 Elektra dropped Spoon’s A Series of Sneaks virtually unnoticed into a three-sided rabbit hole of cultural legitimacy. For its part, Sneaks held its cards close enough to its chest that ubiquity became its greatest feature. Where Loveless’s Hare drowns in the burden of concept, OK Computer’s Tortoise is mired in repetitive bursts of energy, and Nevermind’s Coyote bullies both with its limited character, Sneaks’ Chameleon—a much better student than I—cribs notes from the ideologies represented by all three in an attempt to create music that owes everything and nothing to the behemoths of its cohort. It is art: a concept-driven album that plays inertia and movement against one another as metaphors for individual growth, communal interaction, and persistence in the face of modernity. It is science: its time signatures and arrangements warp and woof off of diagrams penned from intensive studies of the redundant physics of jai alai. It is punk: it shirks conventions while intoning last rites, and, with sacraments fulfilled, circles the corpses, ready to feed. But, above all, A Series of Sneaks is powerful because it is documentary proof that these three ideologies are never mutually exclusive categories.

Brit Daniels may act as the master of this ceremony, but Joshua Zarbo and Jim Eno play equally critical roles here. Much of the beauty and tension comes from the incredibly interesting way Spoon plays with rhythm. The initial sounds that grace your ears, two clangs of a gamelan drowned in static, foreshadow the eclecticism of Sneaks. “Utilitarian” proper begins when the static cuts and a thick crunch guitar plays a Muddy Waters via Wire hook (simultaneously ranging and insular) over which Daniels sings, flails and bends words like “security” and “catacomb” to fit a non-intuitive stop/start meter. After Brit gasps, “I’ve got meat in my arms / I’ve got steel in my teeth / So come on,” a distant voice on a CB radio enters the mix, followed by a delayed percussion note that ricochets in pitch on each echo, sounding somewhere between a handclap and a gunshot. These are minor adjustments to a straight pop song and are subtle in the way they color what otherwise might be mistaken for convention.

“The Guest List/The Execution” features some of the laziest whistling ever caught on tape. “Reservations” opens with a brief reverse-guitar passage that, if looped, would comfortably fit a Fennesz rhythm track; the song proceeds as Daniels alternately syncopates the verses and falls into a reverbed croon for the chorus. “Car Radio” is adorned with brief snippets of shakers that sound patently silly over the fills Eno slips into the mix. “June’s Foreign Spell” creaks with delayed guitar squalls that sound as if part of the mix is skipping while the rest powers through the malfunction; when the heaviest song on the album suddenly morphs into one of its prettiest melodies, the effect is, to say the least, jarring. “No You’re Not” spits and glistens through the return of the distorted handclaps and ends sputtering with reversed vocals and a fucked-up piano take that offer no closure to what would otherwise be a serviceable pop tune. “Advance Cassette” weaves all of these elements into my favorite Malkmus/Olivia Tremor Control collab ever. Tension through humor, tension through juxtaposition, tension through movement, and tension through space—Spoon wages a war of attrition using blitzkrieg tactics.

And it would be easy to end this review here, ‘cause with all of this furious sound, it’s easy to forget there is a message to it all, and one largely missed by the dorm-room crit that presently litters the ‘net. Checking in on Sneaks eight years after its release and four years after its widely available re-release means there’s a lot of dirty laundry to deal with. This album has played victim to a growing aggregate of meaningless modifiers—including meandering, sketch-like, unfinished—that do little more than vaguely characterize a limited view of its purpose. I mean, I guess that for indie kids bred on Nevermind, such unfortunate terms make a kind of sense. Sneaks was released when many of Spoon’s audience (including me) were in the process of pursuing our undergrads, pondering our own futures. The listlessness of the album—and certainly, the 14 tracks shuffle in and out of the album’s thirty-three minute duration like half-jotted stories and unfinished scrub mixes—can be equated with that restlessness, impatience and insecurity.

If one simply considers Brit Daniel’s lyrics on the page, it’s such an easy mistake to make. All of this “meandering” comes off as open space (which Texas, where he’s from, has a lot of). He sits in a stationary car. He descends a staircase to make it “just halfway across the world.” He’s got the potential of a thirty-gallon tank; he opts for action in the backseat. He watches the faces of men and women who drive by his stranded body on a Texas highway. He sets off metal detectors; he can’t get through them. He suggests that the prerequisite to walk in another’s shoes is to “drop two steps back” in your own life. He’s staring (again) at the board in Central Station. He’s inert, he’s utilitarian, he’s jaded and he’s gotten caught. On the surface this seems to be a celebration of lonely On the Road wanderlust.

In hindsight, however, I’m not so sure Daniels wanted all of us to pack our backpacks and head to Europe. Moreover, I think that Daniels has all of his movement (or lack thereof) planned. During “Utilitarian” he notes that he’s walked “46 blocks” without obstacles. Maybe he only wanted to make it “halfway across the world.” While stranded in “30 Gallon Tank,” he still knows exactly where he is: “going down on the century.” He privileges “action” over “abstraction.” On “Car Radio,” he’s “foolin’ around / just a minor on the interstate.” When he gets caught by the metal detector, that’s his cue that he’s “not gonna fake it no more.” In “Metal School,” he has both movement and destination, and he’s conflicted about both. He’s constantly deriding redundant or meaningless movement and talk: the “lazy sue” in “Metal School,” the questions answered before being asked in “June’s Foreign Spell,” the lies in “No You’re Not,” or the inability to provide “a cheap little answer” in “Reservations.” This is not a glorification of the journey over the destination; I see him constantly revelling in both. When he says he’s jaded, I don’t really believe him. When he says he’s stranded on the Texas highway, I suspect he’s kind of happy. I think he’s actually stranded himself, momentarily, to blow kisses on the dusty desert wind (where the boundaries between art and science are incomprehensible) to the very sentiments he’s expressing.

Which are? Bound up in Spoon’s subversive sonics is a calculated centrifuge of music’s past. And I could lazily play spot the influence because, sure, you can hear the Pixies, Pavement, Wire and the Fall. But no matter which influences I point to, they don’t, in my estimation, comprise a valuable way to judge this album unless they are placed in the context for which they are invoked. In 1998, the future of post-punk/indie rock was seriously in doubt. All of the bands Sneaks pays homage to are on its guest list, but they all faced execution. Spoon presides over this ceremony of ghosts as all good hosts should: each time Daniels gets stuck, I hear him seeing one of his guests to the door. With the legacy of his influences behind him, and the possibility, if he stays on their race track, of eventual inertia—of stopping—in front, the directionless nature of Sneaks isn’t about meandering, or enjoying the journey, or trying to catch up with your heroes. It’s about honoring the past and then circumventing the process altogether.

Elektra unceremoniously dumped Spoon soon after Sneaks’ release. The album therefore inhabits a space with other seminal late-nineties works like Secaucus, Con-Art and Emergency & I, works lost in a crucial—and eventually beneficial—shift in the industry. After the great band-grab of the post-Nevermind period, it quickly became apparent that sop like the Goo Goo Dolls, the Gin Blossoms, Bush and Collective Soul were more radio-friendly and profitable than, say, Sonic Youth. The bands that anticipated (and in some cases, still participate) in the indie industry as we recognize it today had to go underground. In so doing, they found new ways of communication, new methods for creation, and new ideas to express musically. A Series of Sneaks is a frustrated but optimistic portrait of this period.

I’m not saying that Sneaks is some forgotten ur-masterpiece that would stand high amongst a forest including Loveless, OK Computer or Nevermind. Its roots, however, spread wide throughout the ground that bore those same trees, feeding off their energy and yielding a gem of an indie rock album. This is the sound of my youthfully irreverent (and irrelevant) nihilism dying. This is a subtle manifesto that “genre” is as arbitrary as the route you choose to get there. This is a damn fine album and as good as indie rock gets, at least before it got way better.