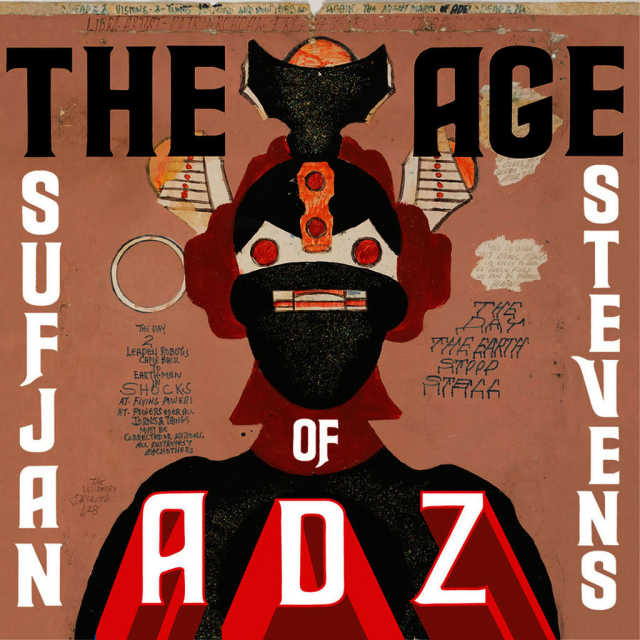

Sufjan Stevens

The Age of Adz

(Asthmatic Kitty; 2010)

By Dom Sinacola | 23 October 2010

No argument: The Age of Adz is the work of a terribly talented guy. Shit is bristling with talent, voluptuous with it—but also beholden to it? See, no one’s arguing Sufjan Stevens isn’t a singular artist; no one’s trying to rain on his parade or tell him what’s what; no one’s hoping he’ll stop being such an ambitious cultural Katamari ball, leveling genre distinctions as if they’re pleasant picket fences dividing identical shades of green. No one’s even really that peeved that his albums are always concept albums even when they aren’t. Everything he does is big and labored and exhaustive, which just means that everything he’s done has always had the potential to be exhausting. And no one is criticizing Stevens’ ace in the hole: his innate comprehension of arrangements, and the way that, animal, vegetable, or mineral, he is able to arrange all of his sound into a fastidiously embroidered corset that binds and holds in his swollen, melancholy core. And since we all know what Sufjan Stevens’ sad, sad heart sounds like, maybe The Age of Adz is just that same, beautiful sound, only now in technicolor. Because obviously this is his best record, right? Because it’s just a lot more of everything we already liked?

I think we’re overlooking some crucial information here. Perhaps the glow of Stevens’ ego is blinding our ultra-sensitive eyeballs. I’m not sure if the way The Age of Adz has been received, heralded, and kept bereft of salient criticism is due to the relatively long length of time between it and Illinois (2005), or due to how universally accepted Stevens’ existential and emotional crises have been, or even due to the simple realization that we’re no longer buying a Sufjan Stevens album but instead Stevens himself. What I am sure of is that The Age of Adz, bastion of ambition and aspiration in the face of your typical uninterested indie posture or not, isn’t all that special. It’s the big box store of Sufjan Stevens albums: something for everyone, but it’s easy to get lost in the wrong aisle.

See, it’s not that Calum’s totally wrong with the basic details: after five years of waiting to see what Stevens would do next, we’re finally offered a Stevens who’s subverted his intentions with the States Project to inflate his own narrative, “making his personal history sound like the history of the world.” Sure, but…have we all forgotten about Seven Swans (2004)? On the heels of Michigan (2003) and as a quiet precursor to the majesty of Illinois, Swans was clear evidence that Stevens had, at the core of all his bombast, a singer-songwriter heart with a penchant for extremely touching melody. The title track of that album, especially, presents a microcosm of what we’ve grown to know intrinsically, over the past decade, about Stevens’ craft: the song is long, it aches with spiritual struggle, it grows towards a climax meant to stir goosebumps from subcutaneous slumber, it exposes his atavistic dread and guilt, and it chides us into accepting his struggle as a universal constant. “Seven Swans” is, for these reasons, an appallingly gorgeous song, and also—despite its seven minutes and choir of voices and grand narratives delivering in gasping, sacred detail a Fatima-like portent blazing in the sky—a concise piece of epic folk. Every instrument has a place, a purpose, and together the purposes collude; when they fuse I’m ravished.

Similar synergy seems like it’s going to happen throughout The Age of Adz. The title track rages out of the gate with fireworks fizzles and spaceship landing noises and strings trilling their brains out—hell, Stevens seeming utterly spent in under 50 seconds. But “Adz” only mounts in calamity from there. The title “Too Much” is just a cute joke; the song suggests there are apparently never too many rhythmic components to run through “mermaid farting” filters. “ I Walked” maps the same landscape, as does “Now That I’m Older” after it, as does “Get Real Get Right,” and so on until the already much-ballyhooed “Impossible Soul” crams 25 minutes down our already exhausted brainpans, getting away with Auto-tune, cheerleading, whatever else is left of any modern mainstream detritus to which Stevens has been partial in the past five years. Even “Bad Communication,” the album’s shortest track at all of two and a half minutes, throbs impatiently with lazer zaps, bloops, blibbles, splashes of turpentine, more and more voices, kadiddles, a mandolin maybe, the ploopy facsimile of E.T. picking his nose—I am running out of conceivable onomatopoeia for this crap.

I’m sure you get the point. And by “you,” I mean one of two kinds of people on this planet: those who see The Age of Adz as half full, and those who see it as half empty. Or, to use Stevens’ vernacular: those who see the album as too much and…those who see the album as too much. Because I think we all see the same thing here (and him scaling the Billboard charts means he’s reaching more “you”s than ever)—we all see an album absolutely aureate. We all see something loaded to the gills, pulsing with ambition.

Please don’t get me wrong: I’m not trying to draw a line in the sand here, to encourage our readers to pick a side, mine or Calum’s, and then from my Hate Fort whip mudballs at Calum’s cherubic face lit rosy by the enjoyment of The Age of Adz, his attention ignorant of my grumblings because he’s focused on the limitless heavens while I’m steaming in the gutter, which is where my Hate Fort is, next to some exasperated f-bombs. See, I think it’s pretty obvious that Calum and I are talking about the same thing here. He calls him Sufjan and I call him Stevens; he’s a big fan who’s been waiting for this for a long time, interest only mildly piqued by the All Delighted People EP (2010), and so am I, scout’s honor; he sees The Age of Adz as the latest testament to ambition from an insanely prolific musician, and so do I. But where Calum revels in that glut, loving how Suf’s peeled back the distance of his historic narratives while re-peeling the stinky onion of his globular sound, I find a musician at his most unsure, no longer in control of his mighty talent and ambition, no longer capable, as he was on “Seven Swans”—as he was on Michigan and Illinois—of making essential music.

Consider: “I’m not fucking around,” Stevens declares, working blue, knowing he’s never used such language in public before, but by that point, waist-deep in the cosmic mess of “I Want To Be Well,” we already know that. The Age of Adz is not the sound of a guy fucking around; in fact, it’s far from anything I’d call “fun.” It is long, harrowing, sometimes even thankless, like long division with too many remainders or an unbalanced equation with Xs, Ys, and Zs hanging in the ethereal void to forever remain unfilled. It’s math; it’s empirically, logically unempirical. It is indescribably overblown. And voila: people fall all over themselves to unlock the secret of this new, experimental approach Stevens is taking to music, conveniently forgetting that he ended Illinois with a near-perfect homage to Steve Reich’s Music for 18 Musicians that also worked thematically in the context that album. All of this particular clatter doesn’t add up to much beyond a claustrophobic awareness of the UI grids that mark off measures in whatever DAW Stevens stitched this stuff together. Because let’s be clear: The Age of Adz is unsettling not because Stevens deploys this new palette; it’s unsettling because he’s had five years to figure out how to make this shit work and…it really doesn’t, I don’t think. The new experience this album provides, at least to me, is that for the first time you can hear the seams of Stevens’ overwhelming arrangements.

And even that would be fine, since the other thing that nobody is arguing is that Stevens must necessarily remain tied to an acoustic, intimate, confessional aesthetic, or that overdubbing wasn’t a necessary component of his previous works. The problem I have is that this sound that Calum sees as exciting and rife with possibility I find unnerving: “when will ‘Vesuvius’ will fall apart?”, I wonder. “Is it when its sweet and awe-struck melody is overrun by that obnoxious squeal Stevens shunts into the midst of an otherwise hushed, patient piano ballad? Not to mention the background gibbering, the gasket-blowing ‘beat,’ the endless echoes, the flute-lead intermission shat all over by that infernal squeal?” I can just imagine that conversation in the studio: “OK, I’m going to give you a kazoo and a distortion pedal, and on the thirtieth time I sing the refrain I want you to just flat-out ruin the whole song. Sorry: fucking song.” It’s infuriating to listen to Stevens kill every pretty, unadorned idea, and then beat every tainted idea to fucking death. And that’s when the excitement of this album becomes a chore, when a song’s already tumbled in on itself and the listener can either give up or strain through the rabble to find the one sound, the one note or splash of humility, to keep the thing grounded. And even that approach is flawed, frankly. Consider the middle section of “Impossible Soul,” the album’s triumphant, cheerleading-led, anthemic centrepiece, so exhilarating for the four minutes or so that it lasts. Some might find solace there, but in the midst of a 25-minute track, bookended by auto-tuned vocals and portentous builds and ebbs, this beautiful moment is so underlined and highlighted and starred and bookmarked as the clear thematic Moment of Clarity for the rest of the album that it becomes its own negation. And then, to make sure that point is driven home, the entire sequence is essentially replayed at half-speed, which…valid creative decision? Sure. Fun to listen to? Meh.

It’s perplexing. Stevens seemingly knows enough about complex song structures and composition that it seems odd that he’s built each of these songs and then layered such incongruous, distracting, unearned, manic noise on top of them—which is another frustrating issue, because rarely does the noise seem integrated into the song structures. He’s done the intimacy thing before; he’s pared down his talent before; all this he’s done before, but never before has his work been so buffeted on all sides by contradictions: that glut is the same as ambition; that ambition is enough because it’s ambitious; that spare, colloquial lyrics are concise; that electronic instruments only make electronic music; that A Sun Came (2000) and Know Your Rabbit (2001) represent both past Stevens and future Stevens; that Sufjan Stevens is alone in his existential crises, his problems voluminous enough to sink this noisy world. CMG’s Mark Abraham has pointed out that the closest analogy to The Age of Adz he can think of is Todd Rundgren’s A Wizard, A True Star (1973), another tortured, labored example of a studio genius drowning his own work in half-assed gropes towards “experimentation” but still offering, in the form of “Just One Victory,” a stunning example of cathartic release. It’s a sad comparison, because that album essentially marked the end of Rundgren’s relevance as a musician and composer in his own right.

Here’s hoping that doesn’t happen to Stevens. See, I used to get inspired by him, and I still want to be: here is someone who has talent on a level I can only dream of; here is someone who comes from the same area where I come from; who writes about all the places that influenced me deeply throughout my whole life; and who, despite his grandiosity, speaks with such warm understanding of all the homes and people who have shaped me as a music fan and as an aspiring artist. But I can’t not be confused that The Age of Adz is as shamelessly is as it is. I don’t want to say Calum’s wrong, because I can’t experience his experience with this album. But when Calum talks about how the lyrics are so personal and first person, that Stevens is no longer playing characters, I have to admit that the music itself, at least to me, belies that notion: where he used be be so proficient at letting us hear the sound of his sad, sad heart, the directionless elliptical clutter that defines The Age of Adz just sounds to me like he’s manufacturing an idea of what a sad heart might sound like. What’s worse, it sounds self-indulgent.

But maybe we should have expected this? Really, the criticisms I’m levying at The Age of Adz are not so different than the criticisms I defended Illinois against in 2005. That was, for some, a bloated album. The difference, I think, amounts to two things: the bloat with Illinois was the album’s length (and the ludicrous song titles). But more importantly, Illinois could be grandiose because it was part of such a grandiose—and, in hindsight, possibly self-defeating—project. But we adapted. Before The Age of Adz, those of us who had carried a candle for Stevens had, as the years since Illinois grew and the apparent death of the 50 States project became apparent, decided that we would be just as happy with something simpler: something that didn’t aspire to encapsulate a whole region, something without lengthy song-titles, something that doesn’t have to answer to a whole state’s population, but only Sufjan himself. It turns out that was not so impossible; it turns out this is exactly what The Age of Adz is.

Boy, we made such a mess together.