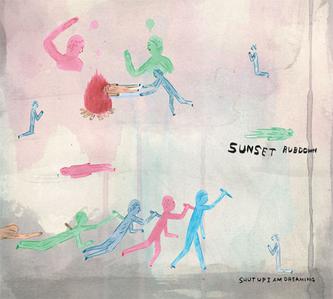

Sunset Rubdown

Shut Up I Am Dreaming

(Absolutely Kosher; 2006)

By Chet Betz | 8 November 2007

I watch American Idol because it’s watching the eternal conglomerate of mainstream culture, mass media and Simon Cowell analogies get its dirty mitts on persons who are pure clay, easily shaped into viable, Billboard-charting pop stars. It’s fascinating, of course. Between the Wolf Parade EPs, Queen Mary and now his shit with Sunset Rubdown, Krug’s currently doing the show one better for me. He’s letting me witness a self-made genesis, and not one to a manufactured celebrity. No, here be the makings of my own actual, personal music idol. Spencer might not have the cheekbone structure of a McPhee, the rock-ensconced cock of a Daughtry, Yamin’s Predator jawline or Hicks’ whatever, but ten years from now when I think all those names were just high school classmates, I’ll still be very conscious of the voice of Spencer Krug. He lifts up hurtling, crumbling tenor strains, mountainous crags of feeling and wisdom. His vocals would destroy Abdul’s soul. A problem that most of these American Idols are gonna have until the day they die, the names of a thousand Dionne Warwicks scrawled across their tombstones, is that they are recording voices divorced from internal voices. No matter how much you might like “Since U Been Gone,” there’s not a chance in hell that Kelly Clarkson’s going to understand a song she sings the way Spencer understands a song he sings.

I’ve already called the man my new Hemingway, even if that only really applies in theme, in his psychological portraiture of the young devil white man’s mind. Krug’s writing is a culture-crosser, though, and he’s a bit like Murakami in how he roots up abstractions from the id’s darker soil with common nouns and adjectives rarely arranged in anything more showy than a compound construct, thus diffusing the danger of pretension while tapping into images both alien and familiar. Compare the opening verse of “Stadiums and Shrines II” (“There’s a kid in there / And he’s big and dumb / And he’s kind of scared”) with the passage from Wind-Up Bird Chronicle (page 301 in my edition) where a nebulous something, “wet” and “slippery” and never before touched, exits a woman’s body during her spiritual rape. I expected Haruki to guest rap verse two. Spencer never lets the clawing undertow of his words drown their catches, though, because most great writers treat language as a plaything, and that playfulness provides levity. “No, I’m not that kind of a whore / But I am a little whore.” The album’s lyrical brilliance is couched in colloquialisms, informalities, rampant contractions and line-starting conjunctions, as a Pynchon or a Kerouac or a Vonnegut or, to be horrifically less flattering, a CMG writer might do. It’s a stripping of self-importance, which is the sexiest sort of strip for my money.

The literary comparisons are out of control, right; clearly, Krug’s not writing prose or poetry, he’s writing songs, and what he’s singing and how he’s singing serve the music as much as the music serves them. Sunset Rubdown players Camilla Wynne Ingr, Jordan Robson Cramer and Michael Doerksen provide really supple support, too, so I hope they forgive me when this piece ends up reading like almost 2000 words of Spencer dick-riding. Shut Up has an unholy strength when its heart spews its life out all at once through Krug’s writ and his voice and the instruments of him and his accomplices. The scree of the anthemic opener gets thrown up in the air and hangs there, suspended, on binary key steps and electric echoes that quickly build then subside to their most primitive and curt, and Krug’s cadence droops past the ends of the bars so that you’re full of belief when he says, “I’m sorry anybody dies in all these days,” shortly before the whole thing falls off a cliff back to earth. On “The Empty Threats of Little Lord,” a discordant mélange of ivory notes clamber in to underscore Spencer’s podium-toppling leap as he sings my favorite pseudo-misogynous line of the year: “There are women with no meaning to their names… when we say them.” The pang of his intonation lets no one off the hook, least of all the name-speakers, and subtle pauses and the emphasis on “them” could end up capitalizing and internal quoting the word, opening up its meaning even further.

There are nits to pick and qualms to stomach, not surprisingly coinciding with those moments where the balance between lyric, vocal and music is off. “Snakes Got a Leg III” is the shit, let’s not get it twisted, but its more tangible greatness lies with those quieter motions where Spencer goes up in to the hills, “not down in the holes,” the exciting gusto of its rock unfortunately compressing Krug’s performance and somewhat obscuring his words. A worse case of the same can be found with “Swimming,” wherein Spence successfully continues his reinvention of the fugue, a heady enough process to distract completely from the singing. And the lyric-vocal two-thirds of the winning Sunset Rubdown formula is excised altogether for “Q-Chord,” your typical keyboard segue between epic tracks; the synth symphonic tones work well enough in execution, but it’s the sort of album construction cliché that feels a notch or two beneath Shut Up’s distinction, which, should it take a flop here or there, seems more suited to flop with the missteps of the adventurous. Case in point would be “The Men Are Called Horsemen There,” a scattered triumph or perhaps just an engaging, seven-minute mess. Its depth immerses its audience in an expanse of otherworldly details, but it’s difficult to bring the sprawl of the experience to a point of focus and to derive proper satisfaction from the conclusion. Exactly the same critique I’d level against Elder Scrolls: Oblivion if I weren’t that game’s bitch.

“Horsemen” also serves as the most extreme example of the way in which Krug carefully disorders the plots and perspectives of his songs into non-linear impressionism, like Nolan editing Lynch, for the purpose of fresh dramatic builds. Structurally, “Same Ghost Every Night” was perhaps most prototypical for how Krug creatively arranges towards resolution, but where that song discovered a huge harmonic, Shut Up more often plays to a sense of duality. The coda of “They Took a Vote and Said No” starts with Krug making his key line red-rover back and forth, then out of the fissure erupts an electric guitar, the explosion of which causes Krug to bang out the opposing chords, forced to wax now that the gap has widened. Draped in watery production finish, “The Empty Threats of Little Lord” ends on a split created by the line breaks Spencer uses to separate “You snake” from the condemning lines that he repeats. As it tickers down, “Snakes Got a Leg III” tries an acceleration of its slow movement into the fast one, combining the two without blending, and “Swimming” finishes with fine music for keyboard that might as well be a counter-melody to the rest of the song that preceded it. And so the resolutions powerfully resolve their respective songs, but feel open and askance and caught in the middle, as well. You best believe I’m headed to Big Statement town.

Compacting fractured particulars into hints of universals, Krug’s speaking to the hallmark flaws of me and my and his generation, our emotional malaise, our social stagnation, our stoned indecision, and he’s transforming those mundane shortcomings into tragedies, bruises into wounds, from which he tears the sutures and so bloodlets like some neo-Romantic. Now I’m rolling my eyes at myself because I swore I wouldn’t deal this album too much presumption. After all, “I’m Sorry I Sang on your Hands That Have Been in the Grave,” taken with its title and sludgy tempo and certain lyric samples, could be labeled necrophilic just as easily as it could be considered desperation’s sequel to “A Day in the Graveyard II” off the EP. Krug’s too smart to show all his cards; I’m too clueless to pinpoint what he’s holding back. Besides, Newell’s Rubdown interviews indicate that Spencer’s songwriting M.O. doesn’t lean much towards capital-c Concept album. Nonetheless, I have to think/project that when the album’s closer drops with its basis for the album title, there’s some import. Because Shut Up finally allows a song to end with a sense of musical and lyrical oneness, one melodic line repeated beneath one imperative mantra of “Don’t make a sound,” which brings a new kind of duality to the context of the whole album.

Musically, “Shut Up I Am Dreaming of Places Where Lovers Have Wings” concludes by repeating the acoustic picking it opened with and then reforming that into a melancholically innervated ‘80s dance affair; Krug’s tone becomes beseeching. When he says “Don’t make a sound,” it feels directed to everyone: to the listeners, to the characters in his song who try telling stories to each other, to himself. Spencer’s asking, it seems, why we even bother communicating and relating as it disrupts the liberating nonsense of our individual oneiric worlds. If life could be described as a solitary marooning, and here we are with all our chat and music and sound-making, trying to bridge the gap, Spencer’s got a bucket of brimstone to dump on the whole ratty shindig. Human expression is incomplete and inadequate, and Shut Up is art about when art’s no longer enough, the sobering after-party to Wolf Parade’s debut. A good example of expression’s inadequacy is my attempt here to show with what nuance and pathos Sunset Rubdown broach the shit out of that simple thesis, for one has to consider the real desire behind “Don’t make a sound.” Krug doesn’t want to lose his dream wings because he needs them, and he needs that need and its hopeless consequences. “So if I fall into the drink / I will say your name before I sink / But oceans never listen to us anyway.” The only thing that’s really changed is that Spencer realizes that, because it is inherent to human nature, the failure to truly connect is inevitable; however, Spencer also realizes that the struggle and the failure can be beautiful. A few knowing steps ahead of Icarus, foresight affords Krug the poise to paint his own fall into a shared vision that is empathetic and stunning.

By turning his voice back on itself, Krug makes his work perfectly deprecate his work to the point where you think for a fleeting moment that just maybe, by virtue of its awareness, Shut Up is uniquely adequate and complete, at least as far as you can mistake it to be. Then you remember “Q-Chord” and the other nits and qualms, and you let your panties dry a bit, even if the distorted burying of words and vocals makes a certain conceptual sense. Still, listen to “Us Ones in Between” with the perception of what this album might be saying about people saying anything in an effort at impossible communion (the album itself party to that effort), and the ballad becomes utterly crushing. Floating up on helium BGVs, the song’s climax peaks: “And I will mutter like a lover / Who speaks in tongues / We speak in tongues / I speak in tongues.”

In the spirit of inanity, I’ll now finish succumbing to my inner Randy Jackson. America, we’ve got a hot one tonight. Three fucking futile exclamation points.