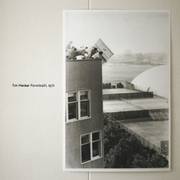

Tim Hecker

Ravedeath, 1972

(Kranky; 2011)

By Joel Elliott | 3 February 2011

I went to Turkey to shoot a documentary on the Armenian Genocide, but I ended up sidetracked by the ruins of the Byzantine Empire. A lot of the relics survived the iconoclastic period heavily damaged: statues with noses smashed in or frescos of Christ and the saints with eyes scratched out. The irony is that, while officially denouncing the visual representation of the sacred, many of these icons were allowed to remain in vandalized form, suggesting belief rarely (if ever) exists without visual form (even the ornate displays of passages from the Qu’ran and Torah are heavily iconographic). It’s about power as much as orthodoxy: when the Byzantine Empress Zoe had her and her husband’s likenesses painted on either side of Jesus, it was to legitimate their rule; the destruction of these images served a similar function.

Tim Hecker claims he was obsessed with images of digital garbage when he came across the photograph of the annual piano drop at MIT which graces the cover of Ravedeath, 1972. He mentions it in the context of the destruction of the physical instrument and the rise of digital music, though I think it’s just as interesting (and somewhat related) that what began as a radical avant-garde gesture in the Fluxus era is now what he calls a “sanitized and sterilized and dignified” frat tradition. It seems particularly relevant in an era where deconstruction carries just as much credibility and legitimation as its object once did; where lo-fi, distorted pop is, at least in some circles, really just pop.

Hecker has always made noisy, metallic sheen sound almost pastoral, but on Ravedeath he comes close to the reverse: analog elements known for evoking nostalgia occasionally veer towards something harsh and uninviting. On “In the Fog I,” piano and organ build into high-end scraping and feedback. The track lumbers and groans, each chord change like lifting a foot encased in concrete. Even after rhythmic pulses are introduced in the second part of the suite, the loops still veer tentatively into the red. A whole album like this suite would be oppressive: it so freely adopts both sacred spaces (the album was recorded in an Icelandic church) and post-industrial landscapes that it sits in a kind of ambivalent void.

In this sense, the echo of memory in the barely-there beats of “No Drums” are a relief, as is “Hatred of Music I,” ironically the most gorgeous track here with its melodies twisting and spiraling upwards. Hecker has always seemed to treat his titles with a somewhat tongue-in-cheek attitude, although “Hatred of Music,” “Analog Paralysis,” and “Studio Suicide,” even if meaningless, suggest at least a lack of resolve that plays out to some degree in the level of emotional return that these tracks allow. The final “In the Air” suite, like so much music that rides the ambient-noise dichotomy, at least provides some sense of quiet melancholy in the insular spaces of its environment (wherever you decide that may be).

Generally speaking that’s good enough, especially since trying to find specific meaning in this kind of music is a largely futile exercise that I and others at CMG still occasionally agonize our way through against our better judgment. Perhaps the appeal of this music lies in nothing more or less than how painstakingly moulded it is, and in that respect Hecker will probably always release really impressive records. Considering all the movements in electronic music that have come and gone in the decade-plus he’s been working—and the degree to which he’s been given a privileged place within that world—he seems remarkably unconcerned with creating massive upheaval, despite being preoccupied with destruction on an intellectual level. Maybe his ultimate aim is to recreate the moment of tension on the cover, just before the piano drops.