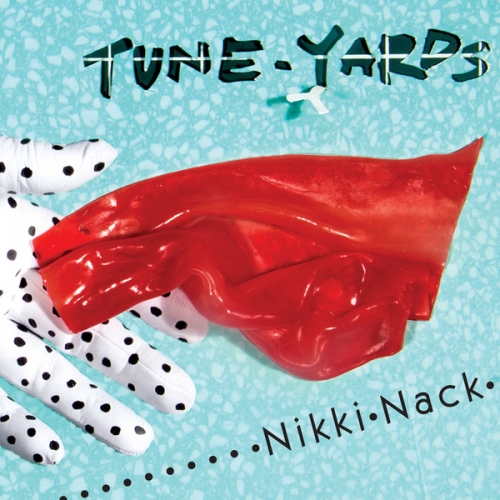

tUnE-yArDs

Nikki Nack

(4AD; 2014)

By Corey Beasley | 6 June 2014

Find me in the basement of the CMG mansion, where they keep the dreamers, the crackpots, the loose cannons. The believers. I prop my feet up on my desk, worn soles finding space between old coffee cups and scattered Illuminati-truther pamphlets. Maura knocks and walks in without waiting for me to answer—her pantsuit is charcoal or navy, but either way it’s a new haircut for a new season, and I wave my partner in from the cocoon of my enormous Jos. A. Bank suit. As always, her eyes flit to the poster hanging behind my desk: a black-and-white photo of Merrill Garbus, fingerpaint or some shit on her face, a defiant look in her expression. I WANT TO BELIEVE, says the poster, and brother, do I ever.

See, some people don’t believe in Garbus. They see the stylization of “tUnE-yArDs,” all those capital letters, and they think, “This couldn’t possibly be real.” Even with all the evidence—her rapturous live shows, her unapologetically political lyrics, her creation of a firebreathing contemporary classic in 2011’s w h o k i l l, her defiant ability to write music on a ukulele that you actually want to listen to—still they won’t believe. Sure, you win Pazz & Jop for your last record, but if you think that business ain’t rigged by Skull & Bones, I got a bridge to sell you. No, I’ve got my ears to the street, and I’ll tell you, plenty of people think Merrill Garbus is taking the piss.

Maura folds her arms, waits for me to look up from my papers.

“McAndrew,” I say.

“Beasley,” she says.

“That theory I was talking about. Ezra Koenig isn’t a reptilian humanoid from the Babylonian Brotherhood after all. It’s Chris Baio. They always think you won’t pay attention to the bassist.”

“Uh-huh. Listen, Beasley, we have a new case.” She digs around in her purse, pulls out a cell phone the size of an eggplant, and then a compact disc. She slides the latter onto my desk. “Nikki Nack,” she says. “Fresh material from you-know-who.”

“This is big, McAndrew.”

“Don’t get carried away, Beasley. Music is just an aural artform governed by pitch, rhythm, timbre, and other essential auditory qualities.”

“I’ll get back to you on that one,” I say and smile. She gives me a wry look and shuts the door behind her when she leaves.

Nikki Nack. I click open my CMG-issued Magnavox boombox and remove the CD in the tray—a promotional copy of an unreleased Panda Bear single made entirely out of weed, and possibly released by the CIA into fashionable Brooklyn neighborhoods for purposes of mind control—to make room. Don’t let me down, Merrill. Help me make them believe. I press play.

It doesn’t take long before I’m sorry for doubting her. At the same time, I’m worried. I’m not the one who matters. I crack a Red Bull from the case sent to me as a thank you for reviewing the Perfect Pussy record, and I take a long pull. Thing is, if w h o k i l l, with its five-hooks-a-minute pace, couldn’t make believers out of the masses, Nikki Nack almost definitely won’t be the record to do it. Where w h o k i l l took call-response dynamics and brash, infectious grooves straight into the red on most of its material, Nikki Nack’s songs largely take their time to breathe and open up. Garbus’s magisterial voice has never sounded better, but it also lives in her throat more than her chest these days. Less bellowing, more of a controlled attack. What if people don’t take the time to listen?

Adam, from his office above mine, stomps on the floor to tell me to turn the bass down. He’s up late vaping, no doubt. But he has a point—Nate Brenner’s bass holds a place of primacy in these songs, his simple, hips-tugging grooves often anchoring Garbus’s compositions in a dub-inflected holding pattern rather than letting them explode into pop maximalism in the manner of her previous material. Listen to the bridge in the fantastic “Sink-O”—the way we’re nudged to pay attention to Garbus’s refrain, “If I went up to your door, you wouldn’t let me in / So don’t say you don’t judge by the color of skin,” when the percussion drops out of the mix to emphasize the vocals, and how Brenner’s groove subtly sucks the air out of the familiar build-release rock ’n’ roll trick by locking right back into place for the final chorus. His simple riff remains the focal point of the music, instead of ceding ground to a fuzzed-out ukulele and honking brass or a caterwaul of looped and layered drums in the style of earlier songs like “My Country” or “Bizness.” Garbus takes her cue from this restraint, too, finishing the song without resorting to the simple thrill of ecstatic vocal run. In other words, Nikki Nack tends toward stoking tension without breaking it, its hazy, lightly stoned ambience providing a sharp counterpoint to the firebrand progressivism of Garbus’s lyrics.

And with less dissonance in the mix, those lyrics take more of the spotlight here. As ever, Garbus blends self-lacerating confessionalism and political barbs with a hefty slathering of imagistic, sound-oriented wordplay. You could’ve, I suppose, listened to a song like “My Country” and ignored its leftist bent while you danced at the Sig Ep house party, but you’re unlikely to be able to do so with a stunner like “Real Thing,” even though its rhythms and hip-hop textures beg for as much movement as anything Garbus has ever put to record. “I come from the land of slaves,” Garbus sings, her voice front-and-center, “let’s go Redskins, let’s go Braves!” And while some critics are crowing about “cultural appropriation,” it shouldn’t take a cultural studies PhD to see the “land of slaves” is America, and “Real Thing” lays bare Garbus’s deep ambivalence about her homeland’s bloody past and her place in a country that still has a gulf a few thousand Turner Fields deep separating it from its egalitarian ideals and the casual, daily bigotry reflected in every facet of its popular culture. If you want cultural appropriation, she’s saying, take a look at a stadium full of white, Southern men doing something called “the tomahawk chop” with their smiling blonde children every weekend. Otherwise, if Garbus’s use of Caribbean-influenced counter-rhythms inflames your sense of cultural propriety, I’m sure you’re going through your record collection right now to throw away every rock ‘n’ roll LP dating all the way back to Elvis, Jerry Lee Lewis, and beyond for the sake of consistency. I’ll wait.

Point being, save for “Rocking Chair”—a near caricature of a tUnE-yArDs song, all handclaps and embarrassing faux patois—Garbus deftly combines a multitude of various musical styles into a sound all her own. There’s a difference between studying Haitian drumming and using that experience to write a song like “Water Fountain” and just naming a song, you know, fucking “Cape Cod Kwassa Kwassa.” “Water Fountain,” for its part, uses its insistent percussive backbone to lend urgency to its fragmented critique of the way poverty reinforces itself when its grip tightens on communities with scarce resources (“no water in the water fountain, no phone in the phone booth”; an image of a young person saving pennies to exchange for a “blood-soaked dollar” that can’t be cleaned “but still works in the store!”). And just like the sports fans blissfully cheering, with straight faces, a team named the Redskins, the narrator in “Water Fountain” has to deal with people seeing her circumstances and their vice-tight grip and nevertheless condescending to ask, “Whatcha doin’ there?” Whether or not Garbus experienced the conditions she writes about is irrelevant; the force of her music and the incisiveness of her words color the song with an indelibility, an evocation of injustice that sticks in your head and plays on a loop because of the way she marries it to a great melody and undeniable rhythm.

That’s why I believe in tUnE-yArDs in a different way than other acts I love or admire. Forgive the earnestness, but you’re in my damn office, after all. It’s heartening that, to listen to the blissful harmonies and lush beauty of “Wait for a Minute,” one also listens to Garbus wrestling with body image in revealing, affecting intimacy. “Monday, the mirror always disappoints,” she sings with desperate loveliness, “I pull my skin back ‘til I see the joints.” Or, to hear one of Nikki Nack’s precious few flashes of vocal pyrotechnics in “Time of Dark,” the way Garbus’s wordless backing chorus dissolves into a blistered guitar solo and an acid-funk groove worthy of carrying the torch for Fugazi’s End Hits (1998)—how these moments come paired with a story of dejection and oppression, and the liberation to be gained through artistic expression. Protest music offers its pleasures at the cost of having to think about unpleasant things while singing along. Garbus makes it go down easy.

I finish my notes, lean back in my chair. Long night ahead. I’d planned to finally finish pinpointing the Freemason hall where Ryan Schreiber and Sufjan Stevens first met to strike their Faustian bargain. But maybe there are more important matters to consider. I give Nikki Nack another spin.