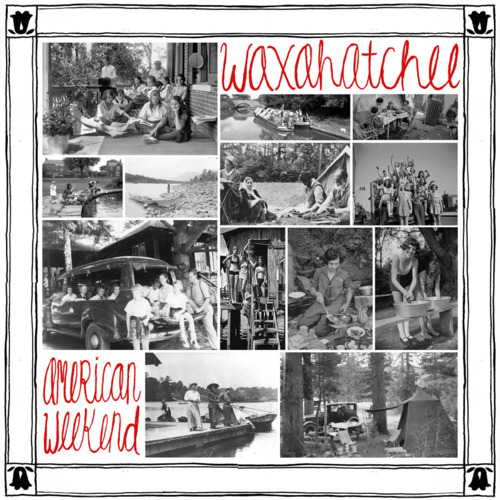

Waxahatchee

American Weekend

(Don Giovanni; 2012)

By Christopher Alexander | 10 January 2013

American Weekend begins during a heat wave. Katie Crutchfield finds a suitable four chord round to send drifting over a languid tempo, appropriate for weather when, as the lyric to “Catfish” declares, it’s ninety degrees at one AM. It conserves its energy. Half notes abound. Static flickers on a television set. Memories move in slow-motion. The window-streak fret noise—the accidental sound that guitarists make on their acoustic guitars when moving their hands across it—is as prominent as the half-whispered words sliding across the edge of her teeth. She’ll sing about Sam Cooke and whiskey—a combination that would make “soaking wet” sheets on the coldest nights–but the song is an exhausted lullaby from humidity. She gives it away when she exclaims “you’re a ghost, and I can’t breathe.” And that’s why this slow, sad song is first. This isn’t the afterglow of lovemaking, it’s the migraine halo of grief.

So things aren’t what they first appear, which makes sense: this song, like the rest of the album, was recorded in a blizzard. Waxahatchee is Crutchfield and Crutchfield alone, snowed in at her mom’s house in Alabama after the dissolution of her band and a relationship or two. Her former concern, P.S. Eliot, were typical of other bands on the Plan-it-X Records roster: they were loud, catchy, and lo-fi, emphasizing folk and twee melodies while hewing fast to the Blake Schwarzenbach lyrical model of sweaty rooms, telling heartbreaking detail, and booze as a community builder, pain reliever, and breakfast substitute. The songs on American Weekend would fit right in, if they were a little quicker and fully arranged. The very next song, “Grass Stain,” cries out for kick-snap drums to back its syncopated “Baba O’Riley” chords, no matter how ostensibly slow it may be. But she’s enough to carry the tune, and, truth be known, she misses her lover more than her old band: “I’ll fish for compliments / And I’ll drink until I’m happy / And I’ll wonder what you’re doing, but I won’t call.” (I, uh, have no idea what that feels like.)

American Weekend, released almost a full year ago, found its way to a few reputable top 30 lists. It isn’t hard to see why from a strictly vulgar, crossover trend-spotting point of view. The lo-fi recordings make her sound very similar to John Darnielle’s work as the Mountain Goats (and there are a few melodic similarities as well, particularly “Rose, 1956” and “I Think I Love You”). The story of its making has strong reminders of Bon Iver’s similarly situated For Emma, Forever Ago. There was also a particularly weak Best Coast album last year, and it’s a vacuum Crutchfield could fill if one is simply inattentive to their musical heroes.

Finally, though, it’s just a damned great album. Think of it as a kind-of Blue (1971) for the basement punk set. Like Joni Mitchell, Crutchfield displays a rare emotional intelligence in singer-songwriters. True, it may be the minimally decent admission that she is capable of being selfish and sad with her lovers. She ignores one all night in “Bathtub,” isn’t sure she even wants to be attached to another in “Be Good,” shrugs when the boy says the same to her. But there’s also the lived-in observation that heartbreak, while it can be reckoned, can’t merely be wished away. Like Blue, American Weekend ends with a staggering one-two. “I Think I Love You” is not the pseudo-vulnerable piety of its title but a terrifying realization that one plus one equals two and broken cell phones and emotionless cigarette smoking equals “You will hurt me / And I deserve it … / I want you so bad it’s devouring me.”

“Noccalula,” named after a picturesque waterfall in Alabama, is a perfect analog to Mitchell’s “The Last Time I Saw Richard.” Crutchfield can’t believe her childhood companions—including her former bandmate and twin sister Alison—are staying in place, getting married, letting the thoughts dance in their head but nowhere else. This isn’t a false farewell to that; like Mitchell, she’s not ready to move on, but she can see it happening. “You’re in the Carolinas and I’m going to New York, and I’ll be much better there, or that’s what I’m hoping for.” She knows the score, and is simultaneously relieved and anxious over fate’s final verdict: “And we will never speak again.” One can scarcely believe this song isn’t modeled after Mitchell’s masterpiece, which is a high piece of musical inspiration as well as lovelorn maturity. Alone with a piano or a guitar, Crutchfield may not want to be left by herself, besotted, at her own table. But if she has more records like American Weekend in her, I think she’ll do alright.