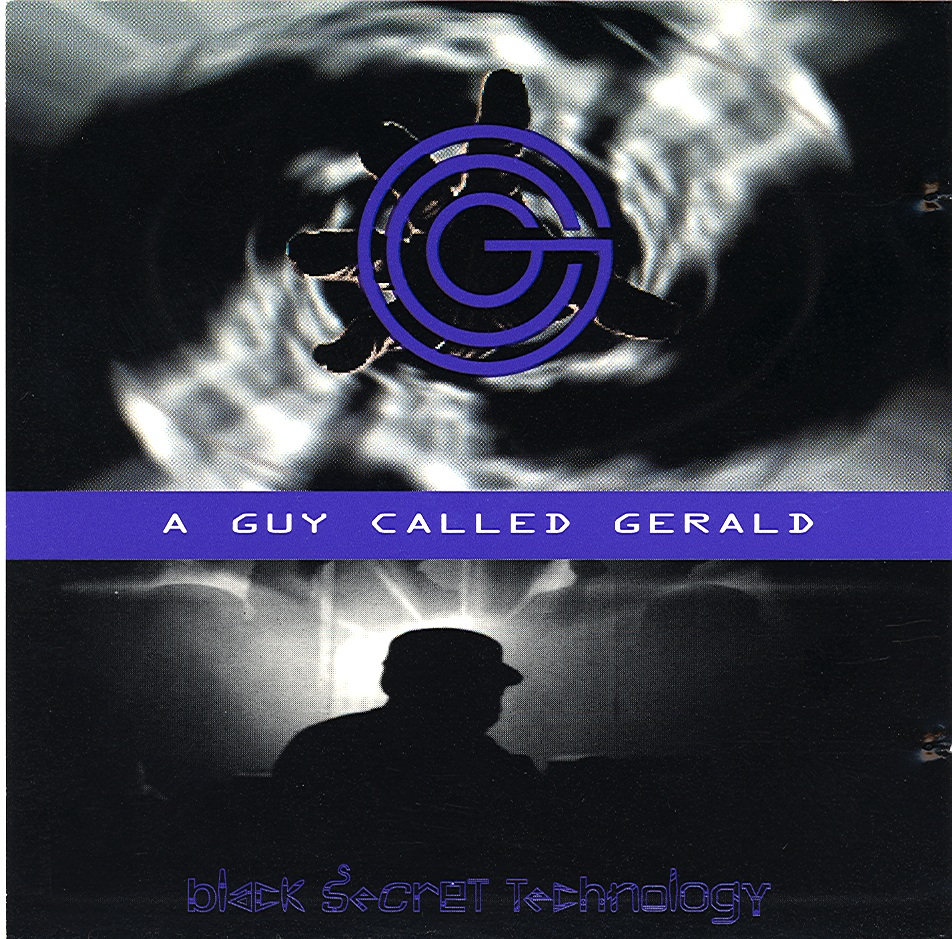

A Guy Called Gerald

Black Secret Technology

(Juice Box/A Guy Called Gerald; 1995/2008)

By David Abravanel | 17 October 2008

What is the value of futurism? It is an aesthetic escape route to a realm of humanity’s greatest hopes and fears; a land steeped in science fiction and looking to dystopia and utopia. It’s no mistake that futuristic novels and movies often imagine a society in which technology can provide ultimate measures of pleasure, but only in back alleys. This is a future where traditional diseases are no longer the problem, but an overpopulated society is suffocating on its growth, spurred on by an omnipotent and omniscient ruling presence. Futurism is a beautiful blue-lit room in which to passionately make love to a soulmate, in the middle of a rainstorm in the middle of a city racked with poverty in the middle of a regime hopelessly lost to the totalitarian madness of an insane few. Don’t laugh: futurism is the escape to beautiful new planets of infinite luxury and feelings so divine as to evade description. It’s the beautiful blinding endorphin of the soul.

In Brave New World Alduous Huxley imagines such a paradoxical world, where the population is kept complacent by soma, a wonderful pleasure drug. I’d not be the first to attend to the potential parallel between soma in the brave new world and ecstasy in rave culture as it started with the second summer of love. I also won’t be the first to hypothesize that jungle represented a kind of come down, or at least a coming to senses. To a happy hardcore raver, the escapism ironically took a more depressing path, nuzzled in denial of the cold world outside the warehouse. But for the more cerebral junglists, starting point may have been the gutter but the destination was still the stars. (A Guy Called) Gerald Simpson and his contemporaries Goldie and 4 Hero knew that the world was harsh, but like true utopian futurists, sought a kind of positive refuge in art. And there’s Black Secret Technology.

A Guy Called Gerald’s pedigree in making this kind of electric sunset-beautiful music can be traced back to 808 State’s breakthrough 1988 single “Pacific State,” for which, it eventually came out, the then-departing Gerald wrote almost everything, leaving Graham Massey and Martin Price to provide a saxophone line and some mixing. Gerald’s contribution included one of the first and finest pad synthesizer riffs in ambient house, but certainly not the last he would produce. Flash forward a few years, and, following a brief but overly compromising flirtation with the majors, Gerald has gone deep underground. It’s the early 1990s, and jungle is a new, raw, and not-yet-commercial prospect, with Gerald as one of its more prodigious innovators. 28 Gun Bad Boy was the first album-length product of this period, a collection on Gerald’s own Juice Box label. Gerald updated his unmistakable brand of techno-soma with stomping breaks and Dickian paranoia. Listened to today, 28 Gun Bad Boy holds up well, much better than other early jungle experiments, but it’s still a prelude to the main event that followed.

”does time work in rhythm…or does rhythm work in time. we have advanced to a level where we can control time solely by stretching of sound…we play with time.“

-from the liner notes of Black Secret Technology

It’s odd to think of time-stretching as such a novel and futuristic technological achievement. Go to the club today (tonight) and the laptop DJ is performing time-stretching on multiple songs at the drop of a hat, creating seamless transitions and perfect mashups. Time-stretching is subtler now, too; where once the granular sound of a stretched sample was self-evident (as it is at multiple points on Black Secret Technology), today we have incredibly sophisticated algorithms for hiding the pockmarks of a messed-with sample. Pitch-shifting used to be this same kind of phenomenally new innovation, before the age of digital tuning applications so advanced it’s hard to tell which pop single uses it, and wisest to choose “all of them.” It can’t just be because it’s 1995 that Gerald’s sample edits are so obvious. He’s sending a message here, playing with the machines rather than playing them, the most sacred respect for these processes being to leave them glaring on the record. Is it really futurism if we can’t assign it imperfections from the present?

Check out “Finley’s Rainbow (Slow Motion Mix).” If “Pacific State” is Gerald’s most well-known pad, this one is hands-down his best. In just four repeating chords, we hear melancholy and euphoria, introspection as it results from the metamorphic social gatherings where all forms of electronic dance music have evolved. Flanked by sparse saxophone and rolling breaks, Finley Quaye croons Bob Marley’s “Sun Is Shining.” This is no cover, but there’s a kindred vibe between Marley and Gerald. Both tracks emerged from frantic environments, and Gerald’s juxtaposition of peacefully slow descending synths cradle Quaye’s suggestions to step back for a while, up against the rushing breaks of society. That Marley was talking about modern pressures and Gerald applying a futuristic bent is the key contrast. The track begins with splashing water and a motherly voice, the latter stretched down to the point where it becomes an oscillating granular tail. I can’t tell what she’s saying, but it’s inviting and warm and comforting. Simple pleasures—a sunny day, bed at the end of hard work, a lover, family.

Part of Black Secret Technology’s otherworldly shine comes from its unusual production, in which the lower-mid and mid range—the pop of a bass drum and the slam of a crisp snare, namely—is neatly tucked away. This latest reissue finally features a decent remastering job; the original was the sort of butchery that gutted the bass from the equation. But even with the levels corrected, it’s the bass lines, mostly very low, that become apparent. Listening to opener “So Many Dreams,” this style falls into place perfectly, as dream-like and ethereal as the material demands. Instead of chopping-block beats and snare rushes, we’re treated to phased and flanged out hi-end symbols, and shorter woodblock and rattle snares. Contrary to popular routes in mixing and mastering, the bass drums on Black Secret Technology are inclined to duck under the bass melodies. On some tracks, such as the beautiful Goldie collaboration “Energy,” it’s hard to even tell if there’s really a separate bass drum and bass riff sound, contributing a certain midnight mystique to the music.

The vocal work on Black Secret Technology further distinguishes the release, appearing mostly through layers of reverb and with a strongly gutted low-end. “Dreaming of You” positions this vocal production with that love-making respite I mentioned earlier, orgasmic gasps weaving in and out of the fold, before finally becoming part of the percussion. From another angle, “Dreaming of You” is chronicling the obsessive nature of a passionate relationship. Moving to melancholy, we’re presented with “Silent Cry,” in which similarly detached female moans and cries enter as more of an instrument than vocals, occasionally layered and pitch-shifted out in a way that makes them hard to distinguish from a synthesizer. Turning once again to Gerald’s liner notes, there’s a suggestion as to what his silent cry is about:

“the first man on earth […] developed a way of communicating which was to become an important part of his survival. these strange patterns of sound were called rhythm, rhythm then was not a leisurely thing, it was a way of life, methods of rhythm helped early man to get in touch with the universe and his small part in it…”

Black Secret Technology, then, exists as a testament to Gerald’s struggle to understand, to connect, to feel something with tradition and individuality and nature in a world becoming increasingly interconnected, communal, and synthetic. As the liner notes continue, Gerald reflects, “i believe that some of these trance like rhythms reflect my frustration to know the truth about my ancestors who talked with drums.” This kind of primal search for connection surfaces with “Voodoo Rage,” in which Gerald revisits his first solo hit, “Voodoo Ray.” In a sign of improving technology, the original 1989 acid house hit was meant to be titled “Voodoo Rage,” but due to the time-length limitations of the sampler Gerald was using, the phrase got cut off as “Ray.” Ironic, then, that improved sampling technology allows Gerald to forge deeper connections with the past and tradition. Using the same sample set as “Voodoo Ray,” “Voodoo Rage” scraps the bouncy, Latin-tinged beats of the original for another foray into pad-laden techno breaks bliss. The titular sample is slowed down to show its grains, infusing the track with the kind of powerful energy Gerald was grasping for in his liners.

Any classic album should have an epic closer, and Black Secret Technology does not disappoint. “Life Unfolds His Mystery” is the final scene in the futuristic scenario that Gerald has painted. The battle of human vs. artificial, individual vs. communal, real vs. fake is over, and it’s hard to say who’s won. The title of the album refers to a television program about secret government operations. As Simon Reynolds hypothesizes in Generation Ecstasy, an album so infused with futuristic technology yet named after a fear-inspiring aspect of that same technology illustrated the drum n’ bass conflict between the “pleasuredome” and “terrordome” potentials of an electronic world. By the time of “Life Unfolds His Mystery,” Gerald appears set to revel in the pleasuredome, focusing his sharp rhythms against the sick infringements of the terrordome. “Such a beautiful…” declares a male singer. Spiritual celebration of life and its rhythms is what Gerald does best. It’s his form of protest, of celebration, of connection with the past, of contributing a reflection of his own soul to the continuum of descending order of aesthetic seekers. It’s not hard to understand why it took five years for Gerald to follow this up (with 2000’s Essence, another fantastic album in the same vein and well worth seeking out). Black Secret Technology isn’t a place to find answers, but more than ten years on it’s still one of the most engrossing, heartbreakingly beautiful, and defiantly hopeful and spiritual records I’ve spent time with.