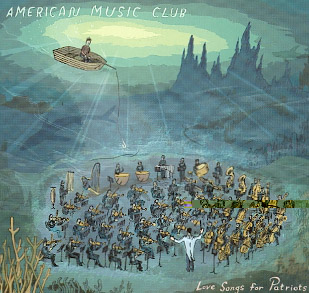

American Music Club

Love Songs for Patriots

(Merge; 2004)

By Amir Nezar | 20 September 2007

As of nearly a decade ago, Mark Eitzel lost his seminal sadcore American Music Club to a failed Reprise Records deal. It didn’t seem to faze the man who’d proven himself as one of the greatest songwriters of the young '90s, even, perhaps, of all time -- he certainly had the awards to show for it.

Moping on with a number of notable (though again, overlooked) solo releases, Eitzel’s career and music didn’t seem even remotely wounded by what his cult of followers initially bewailed as a tragedy. As 1996’s 60 Watt Lining attested, the depressed minstrel of the single brow was more than happy to continue his jazz-inflected songwriting and incisive lyrical penmanship as though nothing (except, of course, more heartbreak) had happened. West then managed to score even higher (and less jazzy) highs merely a year afterwards. And finally, in an almost obscene display of continued inspiration, Caught in a Trap and I Can’t Back Out ‘Cause I Love You Too Much, Baby (1998) achieved the near-impossible: a lead-man-gone-solo had released three year-end-list-worthy solo albums in three consecutive years. It was an unbelievably early high-quality prolificacy that hinted at possible Neil Young-levels of extended solo success.

After his apotheosis, Invisible Man, Eitzel slowed -- certain nothing for which to berate him. Rather, with the release of Music for Courage and Confidence, and the subsequent alternate takes on previous material on The Ugly American (a great deal of which was good old AMC material), it seemed that Eitzel might’ve been longing for the days when he wasn’t bearing his hurt all on his own. And finally, after ten years, he’s sought out his old pain-sharers and simultaneously given AMC-obsessives a reason to shit their pants; the band has formed again, with the addition of pianist/trumpeter Marc Capelle. Long-time fans need not fear the implications of the political bent in the group’s reunion-album title. Eitzel is still the same old self-deprecating -- at times, even self-loathing -- painter of life’s disillusions. In Love Songs he does employ his talents for political allegory; but the allegories are universal as well as temporally pointed, and broken love and illusions still take center stage, anyway.

Just as The Invisible Man employed a dichotomy of spare, Eitzel-ruled melodious tales (on side A) and more fleshed out arrangements (on side B), Love Songs puts full band efforts alongside just-Eitzel numbers. The difference is that Love Songs peppers the album uniformly with both types; it’s a smart strategy, so that Eitzel’s more peaceful upheavals can temper the album’s instances of aggression and lush darkness.

Tellingly, Eitzel’s harshest pieces are his political ones; the drunken swirl of opener “Ladies and Gentlemen,” warns its sleazy lounge clientele, “If you can’t live with the truth / Go ahead / Try and live with a lie,” over cabaret-style piano improvisations and a churning, guttural guitar line. “Patriot’s Heart,” the scathing allegorical tale of an “all-American” stripper who sells his body to the highest bidder, but leaves his buyers -- and himself -- empty, lopes across the hazy bar on a sinister piano melody and pained guitar swipes.

But excepting these two most obvious and -- importantly -- elegant political thrusts, the album is dominated by some deliriously beautiful spare melodies built around frail tales of failed love. “Love Is,” a sweetly smooth-moving, lilting lounge tune, is both a woeful paean and a gently bitter attack. Eitzel croons, “Love is only a lie in the sky / the shadow of a star / flying by,” but then apologizes over and over to his jilted lover, “I didn’t mean to make you cry / I’m sorry I made you cry.” And in a signature Eitzel moment, when he sings, “We’re so small compared to our lullabies,” he draws out the first syllable of “lullaby,” teasing the word towards “love,” only to draw back and leave the romantic illusion empty. The song’s structure shimmers with underlaid synths and a lovely, lethargic acoustic-and-piano melody, smoothly complementing its pensive lyricism.

Following “Love Is,” “Job to Do” is perhaps the album’s best cut. Eitzel contrasts his soft acoustic verse melody with a chorus wracked with feedback, and belabored by heavy cymbals. Instrumentally, he manages to embody his own emotional turmoil over a lover whom he confesses he has to “cross the street to avoid” because she has a “silver lining I can’t shake.” The song’s profoundly tortured bridge can barely hold on to its minor key melody before rippling synths and electronic embellishments shine through its conflicted haze. Ultimately, the song’s deft mix of melodicism and noise is Love Songs’s most affecting statement; it’s an expression of the terrible duality of bliss and torture contained in wounded love.

“Only Love Can Set You Free,” accomplishes a similar effect with just-barely hopeful chorus admonitions, “Listen / Before they force you to your knees / Only love can set you free,” intermittently punctuated with a chiming keyboard melody. Here Eitzel is as hopeful as he has ever been, even if in a bruised way, as he laments, “I’ve got nothing to brag about / Well yes I do / I was once loved by someone like you / I was once in love with someone like you.” Even then, his hurt counterbalances his bare optimism as he finishes the song repeating “I’ve been so lucky,” intimating that his once happy love has now passed him by.

“Home” bullseyes Eitzel’s other familiar theme: self-deprecation and self-ruin. Over a fluttering, kick-drum-led rhythm, and smoothly down-stroked melodic guitar chords, Eitzel crushingly admits “I’m afraid of my own shadow / Because it’s what I’ve become / Why do I waste my time with people who will never love anyone? / My only sin / My only sin / I’ve started hating my own skin.” The song’s rousing rush of a chorus carries Eitzel through a moment of hope to “make it home,” before he returns to yet more lyrical desolation: “The only thing left in this world that bothers to hate me is my pride / No one sees me / They don’t need to / To know I’ve slipped away with the tide.” And “The Devil Needs You” closes with the kind of striking counter-posed melody and dissonant horns that made up some of Radiohead’s Kid A’s (2000) most moving moments.

Little of the album fails to impress in its striking melodic strength or its lyrical intelligence -- which shouldn’t surprise Eitzel’s long-time fans. But the album does have one recurring flaw: overextension of its ideas. “Patriot’s Heart’s" thinly veiled criticism of America is brilliantly wrought, but the instrumental ideas which first keep it afloat start to sink after the song’s fourth minute of reiterated musical themes. “Myopic Books” suffers from over-reliance on a single melodic phrase. And “The Horseshoe Wreath in Bloom,” seems unable to find a suitable ending point, eventually petering out after Eitzel literally and figuratively exhausts his lyrical supply. In an ethic which relies heavily on simple, affecting songwriting, brevity is the soul of endurance; American Music Club forget on a number of occasions that they ought not to stretch their ideas to trying lengths nor wind them through excessive repetition.

Regardless, there is a good deal of understated brilliance on Love Songs for Patriots. As usual, it’s not particularly lifting material; when Eitzel is energetic, it’s usually in the midst of lethal sarcasm and cynicism, and when he does occasionally utter a hopeful word, it sounds like he’s summoning every ounce of dying energy in him to do it. But hey, that’s what we loved about Eitzel and AMC to begin with -- and it’s a pleasure to meet them together again, depressing the shit out of us over a scotch and a cigarette. No other band led by a unibrowed man can do it so well.

Moping on with a number of notable (though again, overlooked) solo releases, Eitzel’s career and music didn’t seem even remotely wounded by what his cult of followers initially bewailed as a tragedy. As 1996’s 60 Watt Lining attested, the depressed minstrel of the single brow was more than happy to continue his jazz-inflected songwriting and incisive lyrical penmanship as though nothing (except, of course, more heartbreak) had happened. West then managed to score even higher (and less jazzy) highs merely a year afterwards. And finally, in an almost obscene display of continued inspiration, Caught in a Trap and I Can’t Back Out ‘Cause I Love You Too Much, Baby (1998) achieved the near-impossible: a lead-man-gone-solo had released three year-end-list-worthy solo albums in three consecutive years. It was an unbelievably early high-quality prolificacy that hinted at possible Neil Young-levels of extended solo success.

After his apotheosis, Invisible Man, Eitzel slowed -- certain nothing for which to berate him. Rather, with the release of Music for Courage and Confidence, and the subsequent alternate takes on previous material on The Ugly American (a great deal of which was good old AMC material), it seemed that Eitzel might’ve been longing for the days when he wasn’t bearing his hurt all on his own. And finally, after ten years, he’s sought out his old pain-sharers and simultaneously given AMC-obsessives a reason to shit their pants; the band has formed again, with the addition of pianist/trumpeter Marc Capelle. Long-time fans need not fear the implications of the political bent in the group’s reunion-album title. Eitzel is still the same old self-deprecating -- at times, even self-loathing -- painter of life’s disillusions. In Love Songs he does employ his talents for political allegory; but the allegories are universal as well as temporally pointed, and broken love and illusions still take center stage, anyway.

Just as The Invisible Man employed a dichotomy of spare, Eitzel-ruled melodious tales (on side A) and more fleshed out arrangements (on side B), Love Songs puts full band efforts alongside just-Eitzel numbers. The difference is that Love Songs peppers the album uniformly with both types; it’s a smart strategy, so that Eitzel’s more peaceful upheavals can temper the album’s instances of aggression and lush darkness.

Tellingly, Eitzel’s harshest pieces are his political ones; the drunken swirl of opener “Ladies and Gentlemen,” warns its sleazy lounge clientele, “If you can’t live with the truth / Go ahead / Try and live with a lie,” over cabaret-style piano improvisations and a churning, guttural guitar line. “Patriot’s Heart,” the scathing allegorical tale of an “all-American” stripper who sells his body to the highest bidder, but leaves his buyers -- and himself -- empty, lopes across the hazy bar on a sinister piano melody and pained guitar swipes.

But excepting these two most obvious and -- importantly -- elegant political thrusts, the album is dominated by some deliriously beautiful spare melodies built around frail tales of failed love. “Love Is,” a sweetly smooth-moving, lilting lounge tune, is both a woeful paean and a gently bitter attack. Eitzel croons, “Love is only a lie in the sky / the shadow of a star / flying by,” but then apologizes over and over to his jilted lover, “I didn’t mean to make you cry / I’m sorry I made you cry.” And in a signature Eitzel moment, when he sings, “We’re so small compared to our lullabies,” he draws out the first syllable of “lullaby,” teasing the word towards “love,” only to draw back and leave the romantic illusion empty. The song’s structure shimmers with underlaid synths and a lovely, lethargic acoustic-and-piano melody, smoothly complementing its pensive lyricism.

Following “Love Is,” “Job to Do” is perhaps the album’s best cut. Eitzel contrasts his soft acoustic verse melody with a chorus wracked with feedback, and belabored by heavy cymbals. Instrumentally, he manages to embody his own emotional turmoil over a lover whom he confesses he has to “cross the street to avoid” because she has a “silver lining I can’t shake.” The song’s profoundly tortured bridge can barely hold on to its minor key melody before rippling synths and electronic embellishments shine through its conflicted haze. Ultimately, the song’s deft mix of melodicism and noise is Love Songs’s most affecting statement; it’s an expression of the terrible duality of bliss and torture contained in wounded love.

“Only Love Can Set You Free,” accomplishes a similar effect with just-barely hopeful chorus admonitions, “Listen / Before they force you to your knees / Only love can set you free,” intermittently punctuated with a chiming keyboard melody. Here Eitzel is as hopeful as he has ever been, even if in a bruised way, as he laments, “I’ve got nothing to brag about / Well yes I do / I was once loved by someone like you / I was once in love with someone like you.” Even then, his hurt counterbalances his bare optimism as he finishes the song repeating “I’ve been so lucky,” intimating that his once happy love has now passed him by.

“Home” bullseyes Eitzel’s other familiar theme: self-deprecation and self-ruin. Over a fluttering, kick-drum-led rhythm, and smoothly down-stroked melodic guitar chords, Eitzel crushingly admits “I’m afraid of my own shadow / Because it’s what I’ve become / Why do I waste my time with people who will never love anyone? / My only sin / My only sin / I’ve started hating my own skin.” The song’s rousing rush of a chorus carries Eitzel through a moment of hope to “make it home,” before he returns to yet more lyrical desolation: “The only thing left in this world that bothers to hate me is my pride / No one sees me / They don’t need to / To know I’ve slipped away with the tide.” And “The Devil Needs You” closes with the kind of striking counter-posed melody and dissonant horns that made up some of Radiohead’s Kid A’s (2000) most moving moments.

Little of the album fails to impress in its striking melodic strength or its lyrical intelligence -- which shouldn’t surprise Eitzel’s long-time fans. But the album does have one recurring flaw: overextension of its ideas. “Patriot’s Heart’s" thinly veiled criticism of America is brilliantly wrought, but the instrumental ideas which first keep it afloat start to sink after the song’s fourth minute of reiterated musical themes. “Myopic Books” suffers from over-reliance on a single melodic phrase. And “The Horseshoe Wreath in Bloom,” seems unable to find a suitable ending point, eventually petering out after Eitzel literally and figuratively exhausts his lyrical supply. In an ethic which relies heavily on simple, affecting songwriting, brevity is the soul of endurance; American Music Club forget on a number of occasions that they ought not to stretch their ideas to trying lengths nor wind them through excessive repetition.

Regardless, there is a good deal of understated brilliance on Love Songs for Patriots. As usual, it’s not particularly lifting material; when Eitzel is energetic, it’s usually in the midst of lethal sarcasm and cynicism, and when he does occasionally utter a hopeful word, it sounds like he’s summoning every ounce of dying energy in him to do it. But hey, that’s what we loved about Eitzel and AMC to begin with -- and it’s a pleasure to meet them together again, depressing the shit out of us over a scotch and a cigarette. No other band led by a unibrowed man can do it so well.