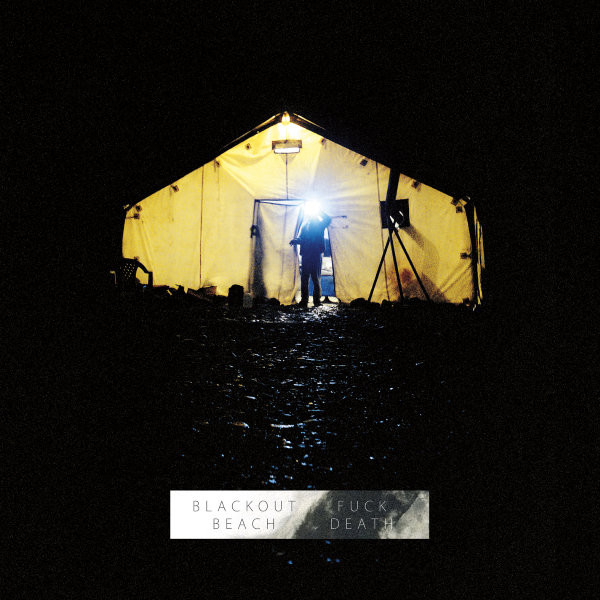

Blackout Beach

Fuck Death

(Dead Oceans; 2011)

By Conrad Amenta | 22 November 2011

I want us to get our critical priorities straight. I don’t want 2011 to be about which albums by people who seem like assholes best capture the quintessence of that assholishness. I want us to be confronted more often by albums that aspire to transcendence in the traditional definition of that word, and I want that aspiration, when we find it, not to be considered exceptional and ambitious, but a fundamental endeavor of the artistic project. I want us to observe this one guy making his mark on a world that continues on in its epochal, disinterested way, regardless of that mark, and to recognize in that failed effort our shared condition. I want this business of music—making it and listening to it and engaging with it critically—to be more than pissing in the wind, and then doing it again because we like our smell, or the way our piss looks. Because most of us forget what’s in our top ten by this time next year; because I have to believe there’s something permanent about music that distinguishes it from a car, or a beer, and that this difference is what makes music worth defending; because Laughing Stock (1991) is a spiritual experience for Chet. And because this isn’t just an excuse to get meta- about music and criticism. Fuck Death doesn’t get a pass because I think music is garbage. Carey Mercer is also good at this.

Mercer named Fuck Death after a painting by Leon Golub, who was an American artist who destroyed his early work and then took terrorism, torture, state repression, and prostitution as his subject matter, experiencing a kind of rebirth by realizing what truly does not matter. The quality of this referent, in and of itself, elevates the record beyond something like, say, Drake’s Take Care (2011), which takes the facets of Drake’s marketable decadence as not only its subject but the universe in which we are forced to orbit. Of course, Fuck Death and Take Care are two different projects, with different goals, but that’s sort of my point. That Drake is someone we might admire instead points to how seriously backwards and fucked up our framework for music assessment has become. (If you think I’m being unfair to Drake, there are dozens of other examples of questionable idol worship to choose from. 2011 seems to be the year we Westerners became comfortable with our status as the world’s hedonistic boogeymen, and if at times it seems like the entire system is falling apart, our sense that we are at the center of things is only strengthened. No wonder we embrace our impulse to say, Fuck it, if we’re going down in flames we may as well be as bad as we wanna be; haters gon’ hate.)

There’s some value in quoting Mercer directly here: “The record is an attempt to make something about Beauty and War. I have very little experience with these concepts.” The fact that he’s talking about upper-case Beauty and upper-case War is key, and also sort of unbelievable and totally unexpected, along with the fact that both, for all this beauty and all this war we’ve experienced, Mercer still finds Mysterious. It’s not enough that Mercer is a serious artist concerned with serious topics—he’s not simply shuffling the deck of today’s priorities—he probes deeper, trying to get at the much larger questions that lie behind existential discussions like those about Beauty and War. Again, I don’t want to valorize this too much, because I think this is what artists should be trying to do anyway. And again: Carey Mercer also happens to be good at this.

All of these and more are the reasons why Fuck Death is not flippant, as the title might imply, but cuts to the core of why you’re even taking the time to read about a record you could have downloaded already and be listening to by now. I suspect that you read music reviews because, like me, you are trying to find something that matters, trying to identify art that rises above the sustained insensitivity and egotism and insecurity of what we call music. Maybe you want music that you can share with the person who created it, rather than music that widens the divide between famous people and their fans. Or maybe you just want Drake. Lots of people do.

Of all the wonderful music released this year, Mercer, it seems, is the only one telling not just death to fuck itself, but is also saying, Fuck this mortality complex and all that flows from it. Fuck relevance. Fuck the mitigations of style and of class. Fuck punk music’s nihilism and fuck the broad strokes of folk music’s politics. Fuck pop music and hip-hop for a million obvious reasons. Fuck all of these things, including you—because what you’re really trying to say when you kick up that squall, even if you don’t know it, is fuck death.

So, by extension, fuck the music industry’s perpetual trial-and-error towards an unachievable immortality. Which Mercer seems more than aware of, choosing to explore that impulse. He says, plainly, on “Drowning Pigs” that “All songs are about getting away.” About Fuck Death he says, “[…] these are deserter’s songs, coward’s songs. I am all for reassessing cowardice. The most important lyric on Fuck Death is ‘run away.’” And so what I would suggest to anyone writing around their mortality rather than about it, is that if you’re going to say fuck death, then say it like Fuck Death says it, which means doing so honestly, and knowingly, and, despite what Mercer says about himself, with courage.

After all, Mercer remains, despite having created one of the maybe half-dozen pieces of rigorous art I’ve heard this year, mercilessly self-critical. His similarly brilliant Skin of Evil (2009) seemed preoccupied with masculine varieties of anxiety, in parts guilt-riddled and antagonistic, a self-flagellation continued on “Hornet’s Fury into the Bandit’s Mouth,” which rails against an easy stand-in for the artist, a “Philistine / Doing what you will, doing what you want.” He talks about “that light” and how we should “Make [that light] ashamed it ever eyed God’s straight light,” and how one’s voice is reduced to a hornet’s loud but meaningless buzzing. It’s equal parts frustrated and confessional; Mercer locates himself squarely at the center of his own apprehensions about this music stuff, still delivering his feverish sermon at the head of the Philistine church, even going so far as to invite a “shooter” to “shoot [him] now.” I choose to believe that in thinking himself subject to these criticisms, Mercer also suggests that something better is possible. I choose to like this self-critical album over the unapologetic ones.

Weird, maybe, to listen to such an ominous-sounding record and hear the strains of what sounds, if not like a Utopian, Transcendentalist’s ideology, then at least like an admission that it could exist. Flimsy stand-in for the long-gone Romantics, I know, but such is our lot in silly 2011. The mere suggestion that the sublime, as a concept, is not so thoroughly compromised has me panting that this record feels fresher, realer, more invested than maybe any other this year. Maybe I‘m just getting tired of trying to find value in a Pepsi ad, or in Danny Brown rapping about blowjobs, or in Kanye and Jay’s perpetual victory lap.

Mercer’s usual impressionistic poetry is run through by his own startling frankness. The album’s central “Be Forewarnded, the Night Has Come,” opens, uncomplicatedly, with the admission “I was sold” only to continue through a series of ascensions and failures: “And the soul has got to soar […] The soul’s enflamed: / The foul wind is rough / I feel it stopping / Deforming my rise,” and finally, beautifully, “You were right / You were the way that I shall rise.” The thing reads, and sounds, like an evangelical epiphany. All the more devastating to then admit, immediately after this discovery, that “War is in my heart / For all the endings: war is in my heart.” Throughout the record, Mercer returns to the themes of light, ghosts, a mysterious “wind” that interferes and is cast in quasi-Biblical terms. Angels and Heaven and Grace and Sin are invoked without irony; the almost thirteen minutes of “Drowning Pigs” ends with an extended, instrumental dirge positively oozing with religiosity. It’s a bracing challenge to music’s stagnant order in its attempted return to a traditional examination of morality and value. And I’m serious: this little album allows itself to be a part of a poetic and philosophical tradition, and does so explicitly rather than figuratively or stylistically.

The album also adopts an appropriately funereal tone in places, with threads of ambient noise married to anachronistic, monochromatic keys and the endless affectation of Mercer’s yelp. His guitar, usually one half of the thorny whorl that makes up the songs of Frog Eyes and Swan Lake, is here largely eschewed, replaced by alien keyboard tones. Yet more value in that, one supposes, for the challenge of making something that isn’t a “guitar album,” but the primary benefit is it’s so much the better to hear and chew on what he’s saying. It’s also beautiful: sound shimmers like the light to which Mercer refers throughout, and then mutates, and then flows like water. He manages to provide breadth to these sparse arrangements, applying his usual scope and lengthy songwriting to take “Beautiful Burning Desire” and “Drowning Pigs” and “Be Forewarnded” to places you don’t think possible at first. It’s as if Mercer’s opened himself to possibilities brasher songwriters have no interest in understanding.

I feel goofy assigning a numerical value to this. I feel as if I should have one year-end list for the records that resonated in accidental, arbitrary ways, and another, parallel list, which contains only Fuck Death, those Strauss and Stravinsky records I bought for a dollar, and the Laughing Stock reissue. It’s not perfect, but in the context of its subject matter one feels like its accidents are worth more than another album’s successes. Mercer has followed up Paul’s Tomb (2010), perhaps one of the most affective rock records in decades (or at least since the last Frog Eyes album), with something which could be read as the excess that didn’t fit in that outfit’s skin, but is more like the distillation of a horror that lies at the center of our misanthropic culture. After all: haters gon’ hate. But fuck that.