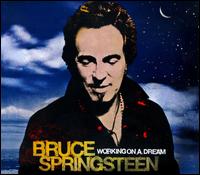

Bruce Springsteen

Working On A Dream

(Columbia; 2009)

By Dom Sinacola | 29 January 2009

Though producer and so-called pal Brendan O’Brien could be championed for, in a sense, revitalizing Bruce Springsteen’s career (as in: contemporizing it, loading it up with post-millennial relevance and such), we’re still talking about the Boss here, and though the distance grows each year (and each release) between my generation and the zenith of the E Street Band’s creative career in, say, precisely the middle of the ’80s, we’re still talking about the Boss here. Working On A Dream will do absolutely nothing to confirm or deny what you—long-time fan; eager music absorber with parental conduit; person from New Jersey that’s not a dick about admitting just how influential this guy is in your garden state instead of acting like it’s some big statement to castigate the very notion of Bruce having any influence on you (and anthems, indie rock, blue-collar showmanship, obligatory sax solos, counter-culture romanticism and how that parlayed into patriotism around the time of, oh, say 9/11, kerchiefs and tight jeans, grease-smeared cheeks, etc.)—have always thought of Bruce Springsteen. At least neutrality won’t sink the Boss’s heretofore summarily unblemished awesomeness; it is perhaps impossible that the Boss will ever be so clueless, so old, as to negate the vitality of his best stuff and, in turn, of his overall artistry. After all, the Boss is no Prince.

Prince, anyway, tallies his geriatric spots by means of an obsolete algorithm that considers how unbelievable he once was in respect to how out-of-touch he now is and then conflates those two, without being able to tell the difference, as a standard for continued marketability. Springsteen does something of the opposite, inflating the everyman ordinariness of his past into archetypal hometown-iness, so much so that it starts to lose its believability, which was always so great about his music in the first place, and then dropping an f-bomb as a sign that his edge hasn’t worn. While Prince tries to become a more believable persona, and so more human, Springsteen streamlines the same sentiment, and together the two lapse into a given existence, meeting at a fork that equalizes their mostly boring trajectories.

Because we’re talking about iconography here, and since The Rising (2002) Springsteen has set the path, whether he likes it or not, for the 9/11 slog towards poignancy. This, O’Brien must tell him, is how American people will still be reminded to care, never forget—that and an insanely energetic live show. So we have Working On a Dream, which only continues in the vein of last year’s Magic by staying vigilant in re-defining, with familiarity, the Boss’ career. In other words: we remember, with our hearts, Bruce. In so easily remembering Bruce we want Bruce, more Bruce forever, but where exactly does Bruce fit in this world so changed?

Same place he always has, turns out: “My Lucky Day” and “What Love Can Do” espouse typically anthemic sunshine noise about harmony and the power of the heart, replete with a rousing mess of the E Street Band’s over-compensating arrangements and “whoa!”s and that one point when Clarence Clemons wakes up. Similar points of familiarity include the darling title track, which paints a subtle licorice bed of piano and feminine backing vocals; “Good Eye,” which is too awkwardly strange, too aware of its almost experimental looping and banjo stomp, to actually seem progressive (like the “Magic” of Magic); and the epicenter of sweet schmaltz that necessarily rests as the nadir of the album, drawing all molten cheese toward it, “Kingdom of Days.” In fact, even the bonus track here, written for Darren Aronofsky’s The Wrestler and another Oscar, attempts to satiate a “Streets of Philadelphia” coda that could have pared the Boss down to his empirical skeleton like his previous award-winning song did, but this new one substitutes gawsh-durn melodrama for any real melody.

Surprising (befuddling) standouts are “Outlaw Pete” and “Queen of the Supermarket,” the former an eight-minute Americana “epic” that opens the album and describes, among many other Old West-ish scenarios, a baby committing larceny. As William Shatner’s said, I can’t get behind that, but only because of the embarrassment I suppress in hearing Springsteen take glee out of such a ridiculous song—not that it’s a song that does anything besides building predictably and bridging movements with big riffs and solos. “Outlaw Pete” just makes the Boss seem a bit naïve, in much the same way “Queen of the Supermarket” (“I’m in love with the queen of the supermarket / Though a company cap covers her hair / Nothing can hide the beauty waiting there.” [Fuck me that sucks]), as it serves up meat and potatoes strings and a condescending gospel singer, can’t possibly be sincere. If it is, then Springsteen’s making some harrowing, counter-intuitive decisions, and all that does is go a long way to sound forced and potentially parodic, which might as well be the bane to any aging icon’s perpetuity.

Bruce Springsteen must know this; Brendan O’Brien mustn’t. Over the course of four albums, O’Brien’s devoted so much effort to highlighting and then solidifying the many countenances of this American hero that blandness and schlock were bound, as O’Brien is so apt, to make their way into the mix. Surely, if the Boss calls O’Brien a friend, friends don’t let friends put “Outlaw Pete” at the beginning of the album; friends don’t let friends allow “Queen of the Supermarket.” So, I doubt your friendship, Bruce and Brendan, this friendship that has slowly turned the Boss into a shell of middle-America idealism without actually altering his sound any more than focusing some on the melodic kernels of each song in lieu of pushing the whole E Street Band to the forefront, working on a din. This isn’t progress, it’s pleasant, capable, effortless stagnation; the dream’s already finished and we can’t, for the love of everything, recall what it was about.