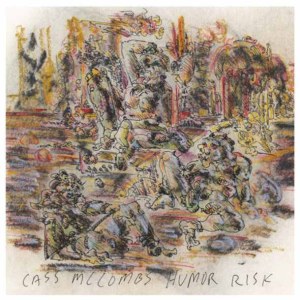

Cass McCombs

Humor Risk

(Domino; 2011)

By Andrew Hall | 17 November 2011

A decade into his career, Cass McCombs’ songs continue to eschew overt autobiography in favor of densely-stylized lyrical arrangements, seemingly more fixated on the internal than the external. Yet McCombs must be given credit for his ability to surprise; Humor Risk, his sixth album, comes only seven months after Wit’s End and could not possibly be more different despite sharing producer Ariel Rechstaid and a handful of collaborators. In fact, it’s practically Wit’s End‘s inverse; it offers the same number of songs, yet trades its predecessor’s icy austerity for warmth and motion, making it a welcome surprise from a musician who proves himself less and less predictable with every record.

If the gorgeous and desperate “County Line” set the tone for the following seven songs’ examinations of memory, frustration, and longing, Humor Risk‘s first track, “Love Thine Enemy,” sets up everything that follows as at least slightly closer to being at peace. McCombs uses its first line, “Love thine enemy / But hate the lack of sincerity,” as the gateway into a collection of songs that sound more contended yet prove to be just as fractured, more of an ambivalent coming to terms than the outright bloodletting that was much of its predecessor. McCombs dissects the line atop the first driving rhythm he’s had on a song in years, building to a bridge that then finds itself overtaken by a field recording and a moment in which, for a single word, his voice is suddenly reprocessed through a vocoder before everything quickly returns to that initial groove. It’s a disarming, disorienting first few minutes, and it makes apparent that McCombs’ refusal to stay in one place spills over into every aspect of what he does.

In practically alternating order, then, McCombs sequences songs that either serve to showcase a melody or to put focus on anything but. “The Living Word,” for example, is arrestingly pretty, with its vocal lead overpowering virtually everything but the organ hiding toward the back of its mix to great effect, and “Robin Egg Blue” comes close, with acoustic and electric guitars split across the stereo image and individual fragments turning into unexpected hooks. Between the two is “To Every Man His Chimera,” which practically takes one of Wit’s End‘s most unsettling moments—the point in “Hermit’s Cave” where what was probably a snare hit but sounded more like a balloon being popped directly into a microphone in an empty room—and hides phone calls and dog barks, among other details, in what would have likely been negative space on any of his last three records.

However, the biggest leap comes in “Mystery Mail,” which traces a story of failed drug dealers through relatively straightforward narration, following how both the narrator and his collaborator meet their ends over an arrangement that practically pushes at country rock; in a parallel universe it could be a Wilco song. McCombs’ heavy stylization and classicism doesn’t suddenly vanish when he has a story he wants to communicate in less than obscure terms, but it serves as compelling evidence that his often-cryptic presentations come less as a weakness as a songwriter than as a something he deliberately does to obscure these details, making a song push at more of a singular, unified feeling than any lyrics sheet could do on its own.

Whether or not Humor Risk is actually much funnier than Wit’s End is another question entirely. McCombs would, as he did in a recent Pitchfork interview, insist that its predecessor had jokes, though the majority of ears, mine included, don’t really hear them. This record’s penultimate track, “Meet Me at the Mannequin Gallery,” feels almost like it’s built around a joke—McCombs provides a potential origin story for the typical display model’s total lack of features, detailing it down to the frustration and the money lost in the process—but it’s by no means going to leave anyone laughing. If McCombs’ first release this year evoked a sense of baroque horror, this one does loosen up, offering at least a few degrees of clarity in a catalog more defined with each passing year by its creator’s desire to subvert the tropes of his genre and refuse anything resembling an easy reading.