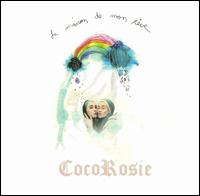

CocoRosie

Le Maison de Mon Reve

(Touch and Go; 2004)

By Chet Betz | 13 April 2004

He sat in the café, sipping on the foreign brew, staring at the two sisters in the park with the birds flying around them.

He followed them in stealth with hat shading his eyes and collar turned up. In his hand he carried a piece of scented pink stationery. Gilded on the pink in elegant cursive:

“Dear Coco and dearest Rosie,

You don’t know me. I barely know you.

I saw you perform at the restaurant the other night. You were splendid. Both of you were splendid.

I can write no more. Please let me have another chance to speak with you in person.

Sincerely, Buck.”

Buck stared long and hard at his name and wished it had been any other name than “Buck.” Then his thoughts became more specific, and he wished that his name was French. He could tell that the sisters liked the French.

At the club the night before, the two girls dressed like gypsies rattled things and played strings. They sang, displaced sirens from the days of yesteryear with the speakeasy and the new factory and the black musician sitting on the corner. They preached girl power and social satire by using the bigot lyric in their winking modern context. “Jesus loves me, but not my wife, not my nigger friends, or their nigger lives…”

Buck came up to the girls after the show, and in the spirit of exuberant over-analysis, he gushed a mix-and-match comparison of their album at them. “It was like, like, I don’t know, maybe if Chan Marshall and Billie Holiday got together to make an intimate blues-folk record in the bedroom of Anticon’s Why? It was different and it gets under your skin, you know?”

Rosie looked cute. Coco said something in her beautifully sonorous voice.

Buck stammered, “Huh, sorry, you have a beautifully sonorous voice. I didn’t hear what you said. You guys are wonderful vocalists, seriously… very nice vocal melodies, too.”

Coco and Rosie harmonized: “We’re not Allen Ginsberg, Ricky.”

Buck: “Oh, see, that’s great, I love that. Uh, my name’s not Ricky, though. And I don’t follow your meaning, either. Sorry.”

Coco and Rosie pranced away while waving their fingers and swaying their hips. A few days later, Coco wrote a reply to Buck’s letter and sent it via the satchel of brooding messenger boy Claude. Buck ripped open the letter to find written in pink ink on a piece of beige paper: “Ricky, I’ll wait for you until the streets become sand, and all the ceilings in New York have come down, and I’ll wait for you until the stars dominate the skies again. I’ll always be by your side, even when you’re down and out. I just wanted to be your housewife. All I wanted was to be your housewife. You will never see Rosie or me again. Love, Coco.”

Claude, the brooding messenger boy, demanded fourteen American dollars.

In very black ink on very white paper, Buck scrawled, “You Brooklyn bitches with your sly imitation of an art form rooted in sincerity, with your affectations and desecrations of Americana, you think the found sound or the lo-fi beats make your music original? It’s cheap atmosphere. You think you can lord yourselves above and away from me in your hip princess castle of self-absorption? Your bare arrangements are gimmicks… with the dawn of the next day you’ve lost half your beauty, that’s how quickly you age. In the moonlight you’re haunting, but just like a ghost, you have no substance. I will miss your voices, and I still adore you both. Love, Ricky.”

Buck handed the ink-spotted scrap to Claude. With a mustered air of bitter sagacity, Buck muttered, “Never chase after clouds and rainbows, boy.”

Claude, the brooding messenger boy, demanded fourteen American dollars.