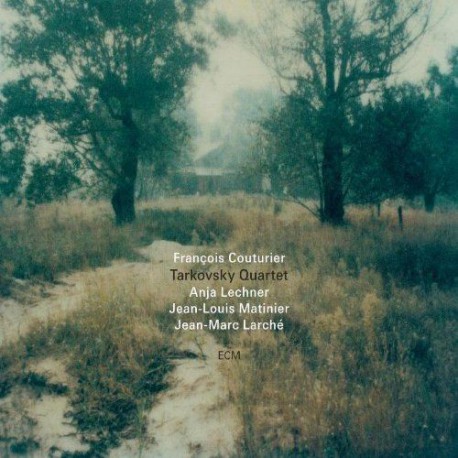

François Couturier

Tarkovsky Quartet

(ECM; 2011)

By Joel Elliott | 1 October 2011

Andrei Tarkovsky called his work “sculpting in time.” It always suggested to me a return to cinema’s origins, before editing had effaced pure time in favor of narrative development. The magic of the Lumière brothers was to bear witness to something unfolding before the camera, to be immersed in the duration of a shot with minimal interference, something Tarkovsky renewed almost paradoxically through one of the most active cameras in film. With this emphasis on uncompromising duration and unfolding, the limits of possibility were constantly challenged. Perhaps that’s why his endings always seemed to consist of drawn out shots illustrating stubborn gestures of faith: Andrei’s crossing of the empty bath with the candle in Nostalghia, the telekinetic movement of the glass across a table in Stalker, or the final montage of icons in Andrei Rublev.

The same obsession with duration and manifest possibilities dots pianist François Couturier’s Tarkovsky Quartet, the third in a trio of albums devoted to the Russian filmmaker. The set-up isn’t exactly that of Olivier Messiaen’s Quartet pour la fin de temps—sub-out one of the strings for an accordion and the clarinet for a soprano sax—but the conceit seems remarkably similar. There are songs called “L’Apocalypse” and “Doktor Faustus,” echoes of destruction and moral collapse, but like Messiaen—who later revolutionized modern composition by placing duration and dynamics on similar scales as pitches—it seems less about the end of time, per se, but the end of an old concept of time.

Whatever it is, it has trickled town to Courturier, whose compositions for this quartet seem to breathe at their own pace: sounds grow out of silence then freely fall back into it like it was so much nutrient-rich soil, while instruments graciously carve out large sonic spaces for each other. Opener “A celui qui a vu l’ange” literally cycles through all four instruments, but in a way that makes them seem like they complete each others’ thoughts: the piano setting the pace, the accordion filling out the sound, cello adding staccatoed punctuation, and the soprano merging them together.

This isn’t jazz—not even of the ornate type typically favoured by ECM—though the main difference seems to be that the melodies filtered down from A Love Supreme (1963) only remain long enough to fit the piece. Individual instruments fade in for one note then vanish. But the spirit is there: “San Galagno” sounds a lot like recent EAI, the accordion playing on the highest register like the humming of sine tones found in more organic laptop artists like Mamoru Fujieda and Sachiko M. “Mouchette” finds pointillistic bursts of sax accompanying the piano which rumbles around the lowest keys as if a fly were darting between the hammers. As in a lot of recent avant-garde music, the idea is to create a complete sound environment, but it never strays away from its structure: the sax constantly oscillating between the same two notes while the piano allowing each thick chord or burst of notes to resonate before moving on.

Nor is this the type of “modern” chamber music favoured by Rachel’s et. al. “Maroussia” contains a baroque-era piano solo (complete with trills and grace notes punctuating every phrase), but bookended by long, minimalist drones that suggest Courturier considers these kinds of retrograde arrangements just another sound to melt into the (chamber) pot. If there’s a trajectory to these pieces it’s easy to lose, a loose, free-association form of composition where every note still seems to have its place. “L’Apocalypse” is a likewise stunning example of marrying structure and chaos (even if in reality it’s all a controlled effect): the track veers the closest to free improv the album gets, but not before the piano/cello play rollicking ascending-descending scales that break-up at unpredictable moments in which the sax/accordion intervene, filling in the gaps in way that creates a continuous stream of sounds as if the quartet were a full-blown orchestra. Even when the tension breaks down in the latter half, the simultaneous density and sense of space is dizzying.

Less easy to dissect is the standout “Mychkine,” where you can almost hear the resin scraping off the bow as the cello is attacked, until the accordion and sax move the track to a crescendo, each instrument seeming to simultaneously lead and follow the other. The default is to call this kind of interaction a “conversation,” which in this case would be as banal as calling Last Tango in Paris a “talkie”: like that film, the interaction of two partners seems choreographed but raw.

But this is a different kind of liberation. Like Messiaen, who wrote his Quartet while in a German POW camp and selected the instrumentation based on what musicians were available, it finds freedom in constraints. Or like Alexander burning his possessions at the end of Offret, both ascetic and reckless. What to say about “La main et l’oiseau,” after all, except that it’s just what it sounds like…the hand, opening up to allow the bird to fly?

Perhaps it’s the humility of these gestures that allows such a bold gesture as devoting three albums to an untouchable master to succeed in the way it does. Like most tributes, it finds its truth in something intangible, beyond either itself or the source of its influence. Sand castles ready to be washed away by the ocean, which is also sculpting in time.