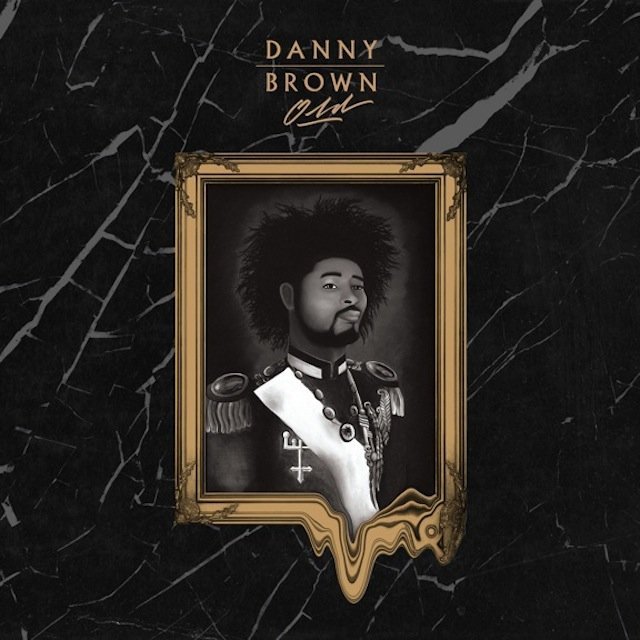

Danny Brown

Old

(Fool's Gold; 2013)

By Chet Betz | 16 October 2013

Let me tell you, it is damn tough to write about Old without comparing it to XXX, its masterpiece predecessor from 2011. Old is the follow-up, after all, and Danny Brown himself certainly doesn’t help matters with the whole “this is my Kid A” business, making a million hipsters percolate. But the comparison is a disservice. I think it’s harder yet to escape that disservice, though, because XXX slung such an intense narrative, if not in a Slick Rick-obvious sort of way; it had characters (mostly courtesy of Brown’s personalities), a thematic core, an arc, a climax, hell, it had flashbacks. It told Danny Brown’s story in a way that was humorous, vivid, brilliant, probably bigger than Brown himself. Without contrition, only the cathartic freedom of truth, it was confessional. Old, on the other hand, is professional. On paper, it seems alarmingly calculated, a two-sided gimmick where Brown first aims to please his old fans in the hood and then later the suburban college students who want to shout along to crass punch-lines over electro-beats. There is something unapologetically simple-minded and straightforward about how Old goes about its business. But when you’re in it, you hear paragon rap music; and, debatably (but not really), the best rap record since XXX.

The record’s dichotomy isn’t completely clear-cut, it’s more yin-yang. Funny that the more offensive material is probably the stuff geared towards the kids in neon tanks, the street raps charmingly innocuous in how few boundaries they look to push. Tired tropes for other rappers are basically Brown’s holy excuse to flow with a wholly clarion mic presence and sense of purpose, an acute/chronic awareness of what he’s doing and his surroundings and how to make us see it all. The first side of Old is Detroit. Really, just that—bankrupt and abandoned. I don’t doubt Brown when he describes how he’s “Lonely” (and how: “Blaming cold air, tryna know my whereabouts / Gone for three days and nobody ever heard about / how I got these Jordans, but that ain’t too important / when I got a bitch pregnant and I’m stacking for abortion”). The lion’s share of the production on this side is Paul White and Oh No, all very Dilla-esque, very appropriate, very good…crazy samples, straight samples, muddy bass, ample drums. Bap ‘til you drop. I think Jay Dee would have loved this record, I think it would have spoke to him, shit, maybe he would have been on it, making Danny a little less lonesome. Side B bleeds through some on Side A: in the rave-jam “25 Bucks,” Purity Ring assist on a smash success to ensnare dope rap in the witch-house; followed immediately by the cracked “Wonderbread,” Brown and a flute loop vying to out-treble each other; then SKYWLKR’s neo-crunk instrumental and Schoolboy Q’s loathsome feature on “Dope Fiend Rental,” foreshadowing the dank decadence to come.

The split from where Danny Brown’s been to where he is and where he’s going is an interesting gap. On XXX it was all melted together, a vibrant rainbow somehow made of shades of grey (way more than fifty and some closer to black than anything), Brown’s ego pushing his id while also getting way fuckin’ high on his own supply. Again, Old is more professional than that. It is all about making that paper. It still revels in depravity and molly and the horizon where language and expression and sensitivity of thought break down and in the sub-strata there is only viscous, vicious rapping…but now it is intent on selling us those things. And it does a hell of job. It does it so transparently, so effectively, so totally and absolutely, it finds its own brand of art in the process. It’s not convincing us to buy, it’s buying us; we give it audience and we’re already bought in. If you’re a rap lover, Old is the kind of record that will own you. Check the way Brown transforms rap biting into motif, he and Freddie Gibbs on “The Return” using “Return of the ‘G’” the exact same way Kast used it, Brown forcefully folding in all the associations for heads that that reference then entails; furthermore, single “Dip” interpolates Freak Nasty and “Niggas in Paris” as Side B’s dark bounce creed, spontaneously conjuring an image of rap titans past and present diving into the deep end of current music trend. But Danny Brown was already there, ready to splash them, cackling, then pass a joint.

Brown doesn’t really exalt the drugs, the sexual absurdum, the materialism; it’s more like he’s saying, “What the fuck else am I going to talk about?” Or, as Danny puts it pretty colorfully on Side A’s culmination: “Nigga, my essay is hard like a life-doin’ ese / gang-banging on the yard with a home-made machete.” This is his reality, and if Brown doesn’t exactly find it a fulfilling or happy one, neither is it one that he truly wants to escape (even if he talks about the possibility of escaping it, sometimes, like on “Clean Up”). When, on “25 Bucks,” he states that he’s “trapped in a trap,” it rings with a trenchant matter-of-factness and acceptance. It’s like the third season of Walking Dead where our heroes hole up in a prison, put themselves in cages, and those cages create a sense of security and home because outside and everywhere, the world is fucked. Whether he’s physically in the Motor City or somewhere out on the sunny festival circuit, Brown carries Detroit with him. As he did on XXX, he is constantly showing us who he was and the fractures in who he is now. But where that was carved in Pac blood into the text of XXX, on Old it is represented in the overriding scheme, adroitly constructed and produced on every level like the best of Drake or Kanye. Old will own you because it erects a steel cage around you, where suddenly your reality and Brown’s inhabit the same space, the space where he talks and you listen. And the beats knock.

Each side of Old ends with exclamation points of artistry, tracks so good they could single-handedly validate each side’s mid-section ruts—and I use “ruts” in the most complimentary way possible, something resolute, stubborn, and grindingly resourceful in how the record spins wheels over the same ground to spray up the dirt ‘n shit and find a grip on bedrock. You probably have to go through the loose vibe of “Gremlins” and the prurience of “Dope Fiend Rental,” for instance, to get to the indelible “Red 2 Go”; through the bilious techno-stank of tracks like “Break It (Go)” and “Handstand” to get to the UV bleed of “Kush Coma” or the fogged-out sunrise of “Float On.” There’s an internal logic at work that can’t really be parsed, only felt. And when Old arrives at its epiphanies, it moves.

I’m not sure what’s better on “Red 2 Go,” Oh No’s beat (which, seriously, is the best thing I’ve ever heard from him, a sonorous turnstile of rhythmic insistence) or Brown’s hook, an inciting, insidious call to the scared and nervous with the response that he’s “Red 2 Go,” after the stellar first verse ends with a perfect distillation of how Brown’s positioning this record in terms of scene and self: “Detroit nigga, but I’m smokin’ on L.A.” Riding a chiming synth line and cool organ exhales, “Float On” finds Brown adopting a Q-Tippy flow to bring home a message of supreme ambivalence: verse one states that Brown would breakdown if not for “these pills,” chemically altering his reality the only way to cope, while verse two suggests that the ultimate goal for Brown is growing old to see his influence on rap, but he doubts he’ll make it—because of the pills. Even for those us who aren’t addicts, there’s a chord struck that’s a root to our being; we all feed on forms of death in order to sustain our lives, undermining our future to deal with our present, and so our past will chase us until we die. We, unceasingly and often willfully, march towards Old. But Danny Brown’s Old is not a tragedy. It’s not particularly sad or remorseful. It just speaks, loud and clear; it dictates out its truth for you to note and ingest, owning your hood/hip ass. Whether you want “that old Danny Brown” or the new shit, it doesn’t matter, because Old takes your demands and ransoms them back to you. As a rap record, it excels. As a galvanization of artistic identity, though, it is unparalleled, both generous and uncompromising. It is Danny Brown, circa now.