Diableros

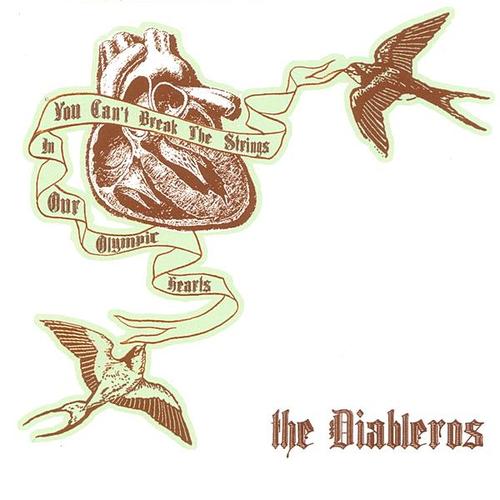

You Can't Break the Strings in Our Olympic Hearts

(Self-released/Baudelaire; 2005/2006)

By Mark Abraham | 28 January 2006

Here’s my confession: You Can’t Break The Strings In Our Olympic Hearts kind of breaks my heart. I really wanted to love it, but our relationship can be nothing more than a temporary fling. It’s a shame, too. Before I heard it, my friends in the music criticism industry made it seem so damn cool. They went nuts about its pedigree: it was performed and self-released by Diableros (yet another six-person multi-gendered Toronto band with a constantly shifting lineup); its debut party was held at an all-night Tex-Mex diner, where, for $10 admission, attendees received a copy of the album; it features a farfisa player, and, according to the scant liner notes, that’s all she plays (hee!); and it sounds like the intersection of a Venn Diagram featuring Funeral, I Can Hear The Heart Beating As One, You Forgot It In People, and Turn On The Bright Lights. This thing should turn me on by on its indie cred alone, right?

I’m a mature individual; I realize things don’t always work out. But at the mercy of Ontario rags (Eye, Now, and XPress), what could I do? At the end of 2005 the propaganda was everywhere, articles and reviews extolling both the humility of the band and the awesomeness of their “anthemic art-rock.” Hell, the press practically adopted Diableros, telling me to get on board before the hype “hits hard.” And…vicious cycle commences.

Dear music industry: hype, when it’s only hype, and erroneous besides, is a shitty thing to do to a band. Xpress extols Pete Carmichael’s “emotionally advanced” lyrics. Could that be referring to such gems as “Sugar Laced Soul?” Carmichael groans, “Don’t you know why people love one another?” His answer: “It’s so they can feel their hearts beat together.” Gag. Eye’s review goes for the clever play on words, suggesting that every single song here “bristles with the possibility of those heartstrings snapping and blood spilling all over the floor.” Sorry, but this thing is about as violent as Gandhi. It’s far too concerned with lush arrangements; it’s worried about heartbreak, not bleeding hearts.

To be fair, the tracks aren’t all so mopey, but the majority follow this killer pop-song pattern: jangly guitar plays riff, band jumps in, vocals start, the production throws the entire thing in a mixer in an attempt to forge the Newman vibe, “yeah-ah” gets thrown about with abandon. It’s all kind of silly and unabashedly derivative, yes, but is it bad? The larger problem here is that, removed from the hype, the Diableros have offered us a perfectly charming pop album. And though it would be simple to pass it off that way (the first five tracks are great but it drags a bit near the end, 68, voila) Diableros are so obviously trying to emulate other, better bands that I just can’t do that.

Diableros and their ilk who aspire to claim a throne in this post-_Funeral_ world must face a certain reality: the unabashed emotions of Funeral, Turn On The Bright Lights, Apologies To Queen Mary, and You Forgot It In People connect with people because the relationship between the personal and political is fundamental to their expression. Block parties, relationships between friends, sex, streetcars, marriage, divorce, vampires, disease—in their worlds, all these things become the building blocks of identity. Personal experience teaches us to interact and act; these albums envision politics not as a state we exist in, but a state our interactions create. And, most importantly to how they sound, in making the personal political, they realize that the difference between happiness and despair (or, perhaps, the sugar and soul) is huge, but the means we have to express both emotions are very similar.

Diableros try valiantly (and the Toronto rags think they’re already there), but they don’t quite make it. Which is fine. There’s nothing wrong with charming pop, and Diableros shouldn’t be faulted for making an album full of great moments: the synergy of synth and guitar on “Tropical Pets,” the teasing melody of “No Weight,” or the absolutely breathtaking musical outro of “Through The Foam.” But they also shouldn’t be shoehorned into an exalted position they simply aren’t ready for. Let’s call a spade a spade: Olympic Hearts is all sugar and no soul, and there’s absolutely nothing wrong with or great about that.