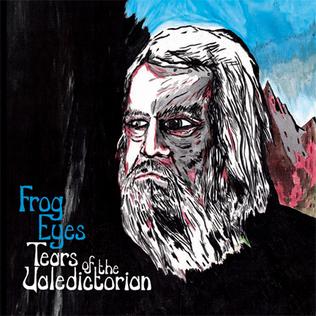

Frog Eyes

Tears of the Valedictorian

(Absolutely Kosher; 2007)

By Scott Reid & Dom Sinacola | 7 June 2007

“Hey man.”

“What’s up, bro?”

Long pause for gratuitous hugging that results from a handshake deemed not effective. One lights a cigarette, the other stares at the grass.

“So, tell me: at what point during Tears of the Valedictorian did you pause, lean forward, remove your glasses, and say ‘My God’ as you rubbed the bridge of your nose?”

“I don’t wear glasses.”

“Really? I thought you did.”

“…”

“Well, what about the point at which you lean forward, rub the back of your neck, find an unsightly neck pimple, and suddenly feel despairingly self-conscious?”

“I don’t have a neck.”

“For me it was ‘Reform the Countryside,’ the coda. Mercer’s singing, ‘And you sing that song that the general sings to the dawn,’ and ‘dawn’ seems to retrieve the mechanical bounce of the ghostly organ and snare tap behind it. He sounds weighted with History but equally alone. That’s frightening stuff.”

“Hasn’t he always had those moments, though? I mean, his voice has always carried that strange liquor made of loneliness and idyllic self consciousness. Even from the beginning, with The Bloody Hand (2002), he was all ‘he sings the tunes of crooks and sheeps’ beside that guitar of his that has pretty much sounded sharp and awkward since always.”

“But Tears of the Valedictorian has got to be the best collection of Frog Eyes songs, ever. Surely you agree.”

“Sure. It’s also the first Frog Eyes album that hasn’t creeped me out.”

“That. And I haven’t gotten as moving an experience out of any Frog Eyes music as I have had during the last two minutes of ‘Bushels.’ There’s nothing loose or unaccounted for. Just a series of segments repeatedly hitting the right sympathetic mark; like all the arrogance and bombast and yelping and blissed out aqueous guitars or pianos of their whole career was building to that very climax.”

“What about ‘Krull Fire Wedding’? That’s off the top of my head. Tightly wrapped song that one.”

“What about it?”

“I just think it might be too easy to accuse — or praise, bolster, champion, whatever — Tears of the Valedictorian for lacking the melodic barriers that in many ways characterized previous releases. The supposed tunefulness of the band hasn’t suddenly emerged from the sharp wreckage of an overly difficult series of albums; I’m confused that the new LP is so heralded as the opposite to some Frog Eyes standard of extremes: like, oh golly, Mercer finally sings instead of shrieks, or instruments can finally breathe where they once were strangled, or their heretical cadence has let up, relented into familiar pop structures. I mean, Mercer isn’t some inchoate preacher now, he’s just always been a loud, mighty pagan, channeling his noise from some other plain. He was ‘singing’ albums ago. Sometimes he even sounded like that guy from Tragically Hip.”

“…Gord Downie. But your semantics are loosening, buddy. You’re ignoring the consolidation at hand; er, at palm. Mercer’s always had a remarkable chemistry with drummer Melanie Campbell (also his wife) and bassist Michael Rak, the core of the Frog Eyes ‘sound’; now, with Spencer Krug back on keys and second guitarist McCloud Zicmuse added, there’s a definite sense of rejuvenation, like this is a band at the top of their game. Maybe that is what some have been picking up on and translating into some ficticious New Frog Eyes outgrowing an anti-pop past. Who knows. They probably got the wrong idea with last year’s The Future is Inter-Disciplinary or Not At AllEP…”

“This record’s aesthetic opposite.”

“Yeah, exactly — or got too caught up in one of their woozy fidelity experiments. And it’s not like Mercer’s esoteric side is suddenly shunned or filtered wholesale into pop gold, it’s just perfectly incorporated into this album’s flow. It really comes down to how effortlessly each member is able to understand and play off of one another, and the advantages of that kind of synergy — especially when led by a songwriter this good — are huge. It’s like what you said about ‘Bushels’: everything’s in the right place, nothing is superfluous. There are no wasted opportunities; whereas some of the band’s older material sounded like elliptical works-in-progress, here each song is carefully gestated, given enough time to organically flesh themselves out.

So I mean, forget how much the Mercer ‘sings’ now, or whatever. What really separates this record is the collective might of the band he’s wielding, and the fascinating directions they’re able to take these songs.”

“Then can’t the same be applied to Notorious Lightning (2005)? Bejar successfully rejuvinated those songs. The cacophony existed, right, but it was more a bulge in his tight jeans than a full ravishing outfit.”

“Dude, you have it backwards. That was Frog Eyes reinventing Destroyer, and not even to that radical an extent. Besides, Bejar is always finding ways to reinvent his sound: changing bands, cities, studios, Bill Cosby sweaters. Frog Eyes were another phase — like the casios on Your Blues (2004), or the sloppy Crazy Horse jams that made This Night (2002) his best record. Don’t get me wrong though, that chemistry’s worth looking into…”

“The chemistry: it’s strange how I’ve niched these guys in my head ever since Swan Lake became a reality. There’s Mercer the Daddy voice, the Waitsian death rattle that refuses to submit even when at odds with its own soaring carnival arrangements; there’s Krug as the grasshopper (Mercer his sensei) achieving the high school quarterback glory that Mercer can only lock in his heart with a secret key; and Bejar as the solipsist’s mold, the impenetrable ‘da da da’ that haunts the trio like a mission statement and a nihilistic boner at once.”

“I didn’t know a nihilist could be bothered to get a boner. Or that boners could haunt.”

“Well, I’ve been haunted by boners my whole life.”

“…”

“…”

“Well, obviously your little triptych of brash indie sorta-pop is a gross muddle of unfair evaluations and plain dumb lies, but goshdarnit chief, it does sound about right. It’s as if you’re pointing to a Rosetta Stone in the album’s text.”

“We’ve got to consider focus, a way to translate this album into something manageable. Otherwise the sheer glut of stuff here would be overwhelming. I’m just trying to find some cynosure, something to hang our hats and ties on.”

“I know. I’m just talking about the dynamic you’ve expressed in the fictional storybook you’ve got going about Mercer, Krug, and Bejar. Each player has a role, a series of duties, and together they make something of a nuclear family. Outside of their yelping Canadian bundle the resources are scarce; few other artists could operate on the scrubby wavelength Swan Lake’s developed. They survive as a unit, as a community, and can sustain an artistic livelihood as long as they never forget the chemistry that defines their unit.”

“You’re losing me, pal. We’re still talking about the new Frog Eyes album, right?”

“Right — Mercer’s no stranger to esoteric lyrics or chortled ‘huh?‘s,’ especially when looking for narrative or narrative authority in his music is a futile brain-wracking. Instead he collects images, often puddles in anachronism, much like a historian.”

“An academe.”

“And we’re left to make connections across time and across cultures, and that’s fucking hard to do. History is hard. Harder is trying to unite these disparate images. They cloud and strike lightning in our brains. In ‘Evil Energy, the ill twin of.’ Mercer repeats (after cutely aping a Bejar non-verbal mewl), ‘For the tempest within us is no tempest without us!’ We’re filled to the brim with conflicting winds and old breath, a storm of authority and truth, of important images branded upon our brains next to minutiae that, hell, could be just as important. But History…”

“…big ‘H’”

“Yeah, it depends on our brain matrix-ing, much like Mercer knows how thick his themes can be and trusts in our sentiments to connect the ethereal threads.”

“Can’t that be said for any art? The best, relatively, are those pieces incomplete without the interaction of an audience, or more specifically, of one person’s revelations and individual experiences?”

“Of course, but consider the translations we’re meant to carry. We’re pummeled with Fathers (Konstantin, Vergil, ‘Aldous,’ Rome) and archetypal titles (the general, cardinal, admiral, boss, captain, sister, brother, father, mother, runaway, monk, breaker, pedlar, fink, ghost, merchant, Valedictorian, Mercer) and expected to intuit the meaning behind the relationships they imply and blank faces they inhabit.”

“…like, we’re music critics.”

“And we’re white and under thirty.”

“So that means that in order to operate under the Music Critic title, we have to assume a certain amount of authority.”

“And develop a community that validates that authority. That believes us.”

“Somehow riffing on one another’s love for music, building commerce around art so that Music Critic becomes a meaningless title at the moment it’s most valid as a social spearhead. At its best, authority is a conduit for relationships, lasting, touching ones, for connections between people. At its worst, authority is simply a reflection of limited resources; kinda who gets what and when.”

“Bingo. Look at ‘Evil Energy’ again. Breathlessly galloping with a whirlwind organ line from Krug, Mercer, barely audible, prattles, ‘And like a drunken and besotten father figure of old / Who was pushed on an ice wedge out to sea / And he trembles and he trembles and he puts his heart on tremble / And he profits from his guilty memories.’ This kind of senilicide was practiced — rarely — in times of great famine or dwindling resources. Similarly, in ‘Bushels’…"

“…that masterpiece, that great bullying core.”

“The song’s naturally parsed into segments. Refrains become chants, become slogans, become indiscernible howls of release. He mourns, ‘London, you’re cold, but the wheat’s got to last.’ It’s a hopeless cry. The wheat won’t last. Even if the ‘pedlar’ gets around to selling his ‘wares,’ there just might not be enough food to go around.”

“So Mercer is only questioning the Father Figure on the ground of necessity, of livelihood.”

“Because the Father Figure, and therefore authority, community, and any nuclear unit, are meaningless in death, when there isn’t enough to go around.”

One rubs his belly and the other wipes his cheek.

“Dude, are you crying?”

“It’s allergies. Can we just go inside?”

“Hmmm. Bad call.”

“So then what?”

“Hmmm.”

“Hmmm.”