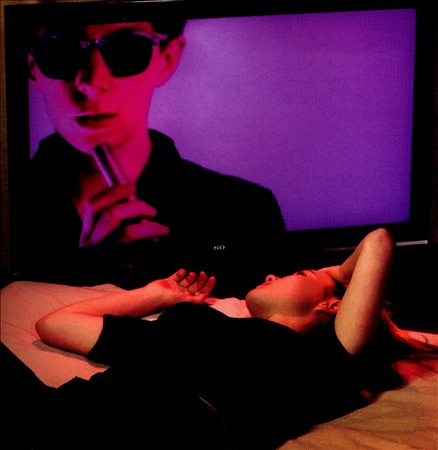

Geoffrey O'Connor

Vanity Is Forever

(Chapter Music; 2011)

By Andrew Hall | 25 October 2011

Geoffrey O’Connor’s debut under his given name is far from his first record. Over the course of the last decade, the Melbourne musician has released several albums as the primary singer-songwriter for Crayon Fields, whose very good All the Pleasures of the World (2009) remains one of the most intricate and accomplished indie pop listens of that year, and as the considerably more stripped down Sly Hats, which served as his solo platform until now. Though O’Connor is probably consolidating his projects under the one name to, I dunno, improve his recognition as his career progresses or whatever, the change also serves to mark major shifts in his approach as a producer, performer, and arranger.

Like its predecessors, Vanity Is Forever is an indie pop record. But it finds O’Connor trading his former band’s low-key orchestration in favor of synthesizers and drum machines, building lush takes on balladry that showcase his thin tenor as he mines ’80s synthpop and the Balearic pop that Scandinavia has gotten so good at exporting in the last several years. He remakes those sounds in his own image as someone simultaneously aspiring to seduce and be seduced, yielding a finished product indebted to epic yet understated melodrama, textural artifice, and romantic melancholy, making it a strong addition and fine entry point into his largely underrated catalog.

Vanity Is Forever establishes its general night-time feel from the first notes of opener “So Sorry,” where a muscular bass line serves to underpin a narrative about a woman who’s transformed her feelings of regret into a wellspring of youth, accompanied by string phrases that likely would have been played by real instruments in his past projects that now sound as if they’re actively celebrating their synthesized origins. From there, O’Connor fixates on regret as a concept more than a handful of times as vague emotions get grandiose accompaniments, putting it, alongside both desperation and the thrill of discovery, at the emotional center of “Whatever Leads Me To You,” where predominantly artificial orchestration weaves around the synth lead that serves as the song’s anchor. However, at no point are his productions trying to trick anyone into believing that they’re the product of a full band; these songs succeed most when their seams show, with absurd sounding sweeps, raw drum machine sounds, and the Roland Juno-6, the same instrument that found itself repurposed and reintroduced to a mass audience by Oneohtrix Point Never’s Daniel Lopatin over the last several years, forming a whole that manages both to showcase sounds and to rarely call attention to them.

Yet his narrators and his songs can’t help but contradict themselves. On “Things I Shouldn’t Do,” guest vocalist Esther Edquist counters him, singing “that’s still not true” as he tries to describe the ways he’s changed over an arrangement that wouldn’t have sounded out of place on the albums Julee Cruise made with David Lynch and Angelo Badalamenti. Furthermore, O’Connor deliberately fuses MIDI and organic elements erratically from song to song, yielding surprises through tight yet meticulously fragmented arranging; “Expensive,” which opens with a plucked acoustic guitar figure, becomes considerably more interesting in its final seconds, as its strings begin to move at a tremolo rate that leaves them practically artifacting in real-time, and the piano-driven “Bad Ideas” more like a Crayon Fields song than anything else here, makes room for a melody so easygoing it practically sneaks by.

Closer “Surely” sees O’Connor use a simple piano-and-voice arrangement to project his final statements on vanity, but chooses to end his record with a simple synthesizer drone, sounding considerably less fragile than either the music it precedes or O’Connor’s own vocal performance. It sheds light on how the instrument serves as a distancing point, emphasizing a sense of disconnect much like Technicolor does for the films of Douglas Sirk, complicating the record’s alternately naive and lustful worldview. However, it still comes across as considerably less bombastic than the Cinemascope-by-comparison work of bands like M83, keeping a focused set of songs with almost no detours at its core.

For the most part, then, the album’s greatest revelation is in how O’Connor transforms his surroundings to the point that their frames can now be called into question, something that never crossed my mind listening to his earlier work. As such, though its pleasures may not be quite as direct as his work with Crayon Fields, and its tempos remain thoroughly slow, it remains a standout among a rapidly-increasing number of hardware and software-driven thrillseekers, more than ample evidence that O’Connor’s work is worth taking notice of.