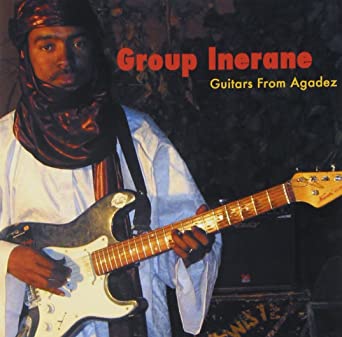

Group Inerane

Guitars From Agadez (Music of Niger) Reissue

(Sublime Frequencies; 2007/2008)

By Peter Holslin | 6 October 2008

The Tuareg people, camel-herding nomads of the unforgiving Sahara in West Africa, are known to perform a unique kind of blues known alternately as Tichumaren (which means “music of the unemployed” in their native tongue of Tamasheq) and simply “guitar music.” In the ’90s, it sprung up as a form of local communication—often the only means of distributing information, cassettes of Tuareg bands like Tinariwen spread from refugee camps in Lybia and Algeria into the villages deep in the Sahara and Sahel deserts, telling the news and calling for freedom from oppression. But over the past several years, the genre has rocketed to international fame and taken on new meaning. It has spoken to oppression worldwide: In 2003, the Navajo traditional/punk band Blackfire performed in solidarity with their subjugated kindred spirits at the “Festival in the Desert” in Mali. And Tichumaren has unified musicians hitherto unrelated: lately, Tinariwen has teamed up with the French band Lo’Jo and… Robert Plant! Guitars From Agadez (Music of Niger), the latest installment of what Sublime Frequency calls the “Tuareg Guitar Revolution,” is a set of live recordings by Group Inerane, a ragtag band of men and women from Niger, headed by Bibi Ahmed, a master of languid guitar grooves. The record is a nice historical document, but it’s the band’s hypnotic desert blues that will make English-language listeners smitten.

Tuareg history could fill a dozen encyclopedia-sized volumes, plus a few language dictionaries and phrasebooks. At the end of the 19th century, after a couple thousand years of sometimes contentious camel herding, French colonists destabilized their society by chopping up the dusty and craggy western desert to make Mali, Niger, Chad, and Algeria. After independence, post-colonial governments still marginalized the independent-minded nomads and they took up arms in 1963. In Libya, famine-ridden nomads learned of revolutionary political theories, listened to Bob Dylan and Bob Marley, discovered electric guitars and other rock ’n’ roll instruments, and eventually formed Tinariwen, the first Tichumaren band. In the ’90s, when a second rebellion sparked up against the governments of Mali and Niger, the flamboyant dictator of Libya armed the movement with more guns and guitars. As the rebellion ran its course, Tinariwen and others cultivated the sorrowful style of Tichumaren and sung of their people’s struggles. After rebels signed a peace accord and burned their weapons in 1996, Tichumaren musicians, some of them former fighters, renounced violence and focused on their music—helping spawn a second wave of Tuareg guitar music.

Of course, the main reason Tichumaren is so popular is because the music is mesmerizing and remarkably unique. The performances on Guitars From Agadez, recorded in the bustling Tuareg city of Agadez and first released in 2007 as a limited edition LP, are not as feel-good as the songs of Malian guitar legend Ali Farka Touré, or as overproduced and sappy as the raï of Morocco and Algeria up north, or as recognizably R&B-influenced as the Ethiopian bands to the east. Group Inerane’s hypnotic jams, marrying traditional call-and-response repetition with the expressive guitar work of American blues, evoke the band’s desert homeland: rough, spare, transcendent but menacing. “Kuni Majagani” hinges on a single note repeated over and over, accented by an infectious melody, men chanting and women ululating. The guitar of “Tenerte” wanders and dances as the drums gallop and the male singer leads a female chorus in an inspirational chant. The intertwining guitar lines of “Nadan Al Kazawnin,” doused in distortion and repeating over and over, grow progressively more volatile. “Ikab Kabau” has the most traditional flavor, led by bouncy tribal drums and clapping. Albeit mellow, this is convivial music, great to sing and dance to in deserts and dance clubs alike.

Unfortunately, most listeners will have no clue what the band is singing about—maybe the wide and lonely desert, or valorous rebels, or love. There’s no lyric sheet, so who knows? The founder of Sublime Frequencies, Alan Bishop, seems to prefer it that way. He recently told The Believer: “If I knew the language enough to know it was a horrible love song with stupid lyrics—like most of the popular songs are today in the English language that I hear—then it would be much more of a turnoff then if it would allow me to interpret it from the expressive capabilities of the vocalizing or of the sound itself, which allows me to create my own meaning for it, which elevates it into a higher piece of work for me.” The same, apparently, applies to songs with revolutionary roots.

A fascinating take on the struggles of a proud culture and an integral chapter in the worldwide rock phenomenon, the songs in Guitars From Agadez are simultaneously traditional and modern, celebratory and wistful. Open-minded listeners are sure to enjoy them, even if they have no idea what’s being sung.