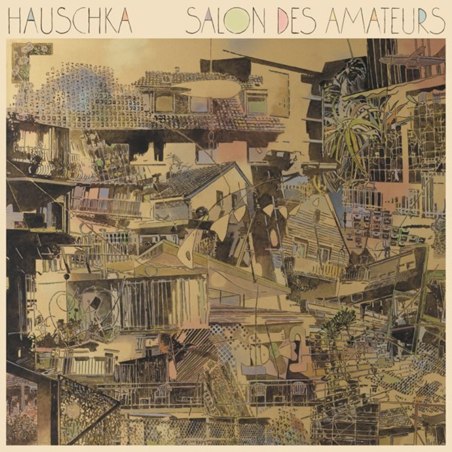

Hauschka

Salon des Amateurs

(FatCat; 2011)

By Conrad Amenta | 18 April 2011

Like pastiche pioneer Daniel Vujanic’s Baja, Volker Bertelmann posits a careful kind of post-structuralism as his starting point. In this methodology, structure is not a tacit system with rules to which the artist unquestioningly adheres—a verse followed by a chorus, for example—but is seen as an arbitrary notion not necessarily to be done away with, but to consciously relocate oneself relative to. This is no rebuild; where the notion of deconstruction might imply a swing to the other end of the spectrum—which is to say, the complete absence of structure—a satisfying balance is achieved when the artist attempts a strategic rearrangement of elements to not totally undermine so much as subtlety refresh these equations. It is the reconstitution of structure to reveal the assumptions we make about that structure. In the past, both Baja and Hauschka have leaned further away from the mainstream than their contemporaries by slicing and subverting that most centralizing of elements: rhythm. But, like Baja did on Wolfhour (2008), Bertelmann here offers a return to that common space by preparing his most structurally dependent, and thus accessible album yet.

Seeing that rating up there, you must guess that I see this as a good thing, and with this being Bertelmann’s seventh album in only six years, I do. What might otherwise be seen as a middling of ideas is here a very natural culmination of a torrid release schedule. It’s not that there is any fundamental departure from his now well-established technique: he continues to combine prepared piano, which is the physical alteration of a piano’s strings and hammers, with pop and electronic aesthetics. It’s solely the unification of rhythmic elements that makes Salon des Amateurs a welcome departure.

Keeping rhythm intact provides the textural, found-sound qualities of prepared piano a new kind of character—less incidental, it seems, than a confluence of patterns and components. Where Bertelmann’s strongest declaration of fidelity to his particular methodology may remain the still-wonderful Room to Expand (2007), Salon seems almost mechanical in its newfound elegance. There’s a true rejuvenation of his approach at play here, as if the disparate constellations of his various works are here gathered, and settled, and made to march in playful lockstep.

One almost feels like a luddite to privilege such a tactile gesture as altering the way a piano works over the sampling and arrangement of its subsequent noises by computer. After all, the latter tool is so powerful as to generate whole new genres where the former defines Hauschka’s entire oeuvre as strictly post-classical. There’s something to the notion, perhaps, that the production qualities for electronic music still has trouble reproducing the warmth evident on a song like opener “Radar,” with its radiant horns, or the low-grade locomotion of “Girls.” Each song is its own self-encapsulating project of tightly arranged, clockwork details. Something like “Subconscious” is expertly meticulous, easy to listen to where it might be exhausting in another person’s hands.

Given the new emphasis on repetition and rhythm, this may technically be, for Bertelmann at least, a “dance album,” but the near-total absence of bass (or low end at all) keeps it light years from anything you’d respond to on a dance floor. And the album does seem to work its way toward an obscure amount of detail, with tracks like “Ping” and “No Sleep” remaining too counterintuitive in their slight shifts in rhythm to really represent a cross-demographic cut. But Salon des Amateurs is undeniably an important album for Hauschka, both for its distillation of his rigorous methods and its energized perspective. It, along with Room to Expand, is an ideal introduction to Bertelmann’s work, which is itself expanding into the impressive catalogue a confident and consummate craftsman.